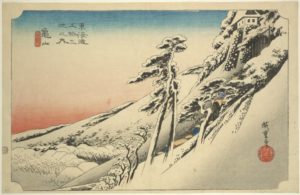

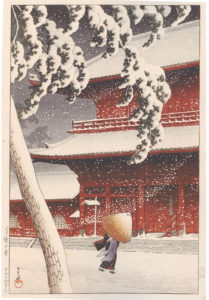

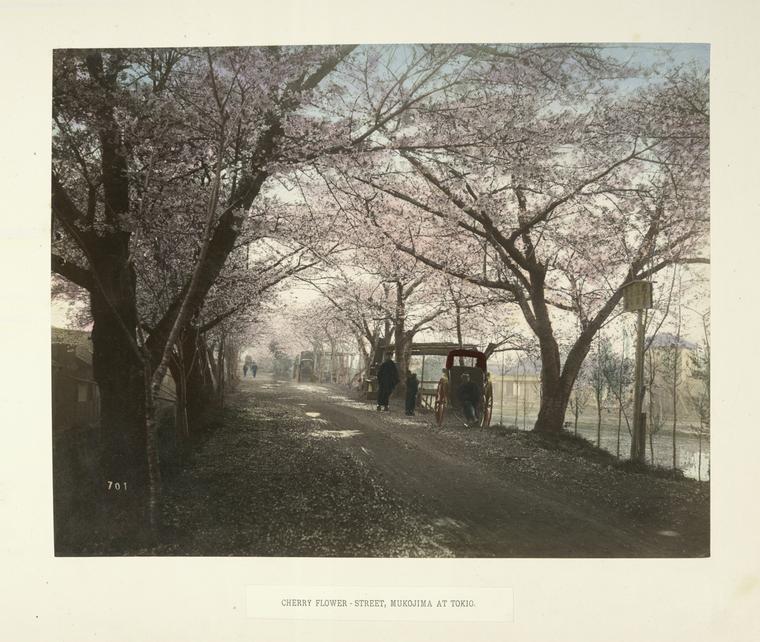

As the heat of summer wears on, winter haiku gives us a chance to think on cold days and all the pleasures of winter. Hot tea. Hot chocolate. Blankets. This collection of haiku includes Basho, Buson, Issa, and a few others. It’s far from exhaustive.

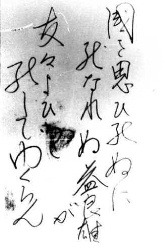

Haiku is a style of poetry that requires plain language and a season reference. It follows a 5-7-5 syllable rule with the 3 lines rarely rhyming. Most haiku seek to suggest a moment in time along with a feeling. It’s tempting to read too much into a haiku. Basho warns us to “prefer vegetable broth to duck soup.” That is, to prefer the literal, plain meaning over seeking something complicated.

Through their haiku you get a sense of each author’s personality. Basho’s work has a melancholy feel similar to the later concept of wabi-sabi. Buson feels observational and more even-tempered while Issa makes you grin.

Haiku focuses on many different topics. Jisei, for example, are poems written before someone dies. The smallness of haiku belies the mix of images and feelings its few words suggest. It’s tempting to read over haiku, but it works better to pause on each poem and savor it. Imagine the picture the words paint and what they suggest. Let’s look at this poem by Buson as an example:

Tethered horse;

Snow

In both stirrups.

I see a cold, wet snow. The horse has been waiting for her master for quite some time. What is her master doing? I picture the horse outside a ryokan, an inn. Her master is enjoying a hotpot with the local farmers who are itching for news from outside their snowed-in village. I sense both solitude and companionship within the fleeting moment. What do you see in the 6-word poem?

As you read these poems, take a moment to notice what images you see and feelings you have.

Winter Haiku Written By Basho

Come, let’s go

Snow-viewing

Till we’re buried.

Awake at night—

The sound of the water jar

Cracking in the cold.

The winter sun—

On the horse’s back

My frozen shadow.

First winter rain—

Even the monkey

Seems to want a raincoat.

Winter rain—

The field stubble

Has blackened.

First snow

Falling

On the half-finished bridge.

On the cow shed

A hard winter rain;

Cock crowing.

The winter storm

Hide the bamboo grove

And quieted away.

Winter solitude—

In a world of one color

The sound of wind.

Awake at night,

The lamp low,

The oil freezing.

When the winter chrysanthemums go,

There’s nothing to write about

But radishes.

The she cat—

Grown thin

From love and barley.

Winter garden,

The moon thinned to a thread,

Insects singing.

Wintry wind—

Passing a man

With a swollen face.

The winter leeks

Have been washed white –

How cold it is!

All this foolishness

About moons and blossoms

Pricked by the cold’s needle.

Still alive

And frozen in one lump—

The sea slugs.

Winter Haiku Written by Buson

Blow of an ax,

Pine scent,

The winter woods.

The sound of a saw;

Poor people,

Winter midnight.

Going home,

The horse stumbles

In the winter wind.

Straw sandal half sunk

In an old pond

In the sleety snow.

Cover my head

Or my feet?

The winter quilt.

Tethered horse;

Snow

In both stirrups.

Flowers offered to the Buddha

Come floating

Down the winter river.

Miles of frost –

On the lake

The moon’s my own.

Winter Haiku Written by Issa

The snow is melting

And the village is flooded

With children.

January—

In other provinces

Plums blossoming.

Napped half the day;

No one

Punished me!

From the end of the nose

Of the Buddha on the moor

Hang icicles.

Writing shit about new snow

For the rich

Is not art.

Here,

I’m here—

The snow falling

Various Authors

Confined within doors

A priest is warming himself

Burning a Buddha statue.

– Natsume Soseki

Winter well:

A bucketfuL

Of starlight.

– Horiuchi Toshimi

At the winter solstice

The sun permeates the firmament

Of the mountain province.

– Iida Dakotsu

See the river flow

In a long unbroken line

On the field of snow.

– Boncho

Glittering flakes:

The wind is breaking

Frozen moonlight.

– Horiuchi Toshimi

References

Hass, Robert (1994) The Essential Haiku. NJ, The Ecco Press.

I think the website is worth visiting. The haikus about winter really appeal to me.

I also recently published a collection of haikus: “The Year That Passes.”

I do not think the modern-translations do justice to these poets, particularly Basho for their heavy reliance on the word “winter”. Kigo are really meant to suggest or express the season in a subtle way. The other bone of contention I have concerns the fact that it requires skill for artists in this genre to confine themselves to the 5-7-5 Haiku-form. The same would apply to a linguist translating these ancient-texts. Also most of your selections here lack for strong kireji. I am a NZ “Kiwi” and author of several books of Haiku poems. Winter is practically over now Down-Under, and a little belatedly I have decided to write a hundred-pages of Haiku from my memories of the past two-months in combination with this unusual-month that remains – it being tantamount to early-spring. Already, I have catalogued several new NZ-kigo with the intent to avoid use of the word “winter” altogether throughout. I look forward to hearing from you…

English has its limits when translating Japanese haiku. We tend to lose the double meanings of Japanese words, as you know. But I’ve seen attempts to translate the feeling of the Japanese but it breaks the Haiku form. I’m not a haiku translator, but it appears it’s hard to balance complete meaning with artistry. Our idea of rain, for example, is mostly singular while Japanese words for rain are based on strength, time of day, season, length, color, and other attributes. We would need a phrase to capture the same effect, possibly breaking the structure of the haiku.

For readers who don’t know:

kireji or “cutting word” are structural words in haiku. Think of them as grammar for the poems. English punctuation is used to translate the contrasting effect.

kigo are phrases associated with a particular season. “Bare tree,” for example, signifies winter.

English kigo appear difficult because seasonal experiences lack universality. I’m sure my experiences of winter are different from yours in New Zealand, so your kigo might fall flat, as will mine on you. Poetry’s limitations are interesting when you consider them. The reader’s experience matters more than the writer’s. For example, “bare tree” doesn’t make me think of the intended negative aspects of winter–grief, distance, etc. Instead, it makes me feel joy, calmness, warmth, and pleasure. I love winter! However, kigo of summer make me feel irritation, unhappiness, fatigue, illness, and none of the intended positive aspects of summer kigo. I dislike summer. While I understand Basho’s intent, I don’t feel the emotion he tries to convey because of my associations. I usually feel the opposite!