Wabi-sabi doesn’t have an equivalent English word. The phrase itself is rather fun to say: wabi-sabi. The phrase describes an aesthetic, a feeling, that underlies our experiences of art and landscapes. The phrase contains two words that, though similar, work together to describe what we in the West would call nostalgic tragedy.

Wabi-sabi doesn’t have an equivalent English word. The phrase itself is rather fun to say: wabi-sabi. The phrase describes an aesthetic, a feeling, that underlies our experiences of art and landscapes. The phrase contains two words that, though similar, work together to describe what we in the West would call nostalgic tragedy.

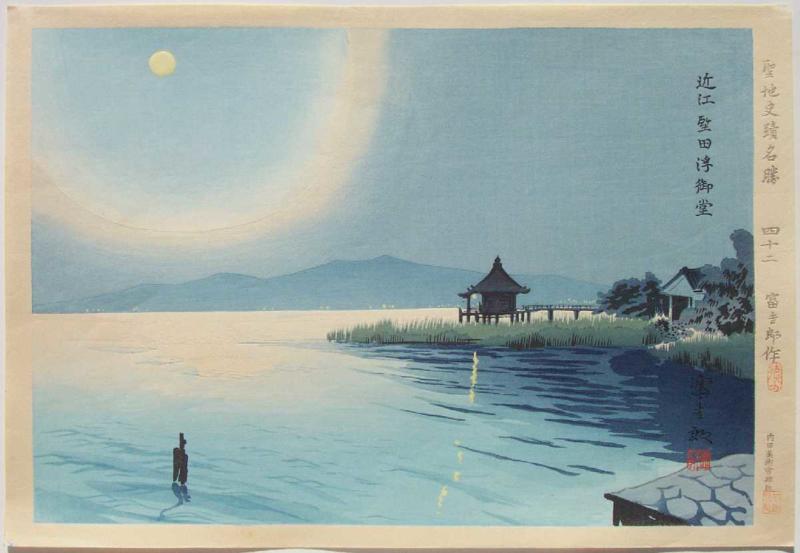

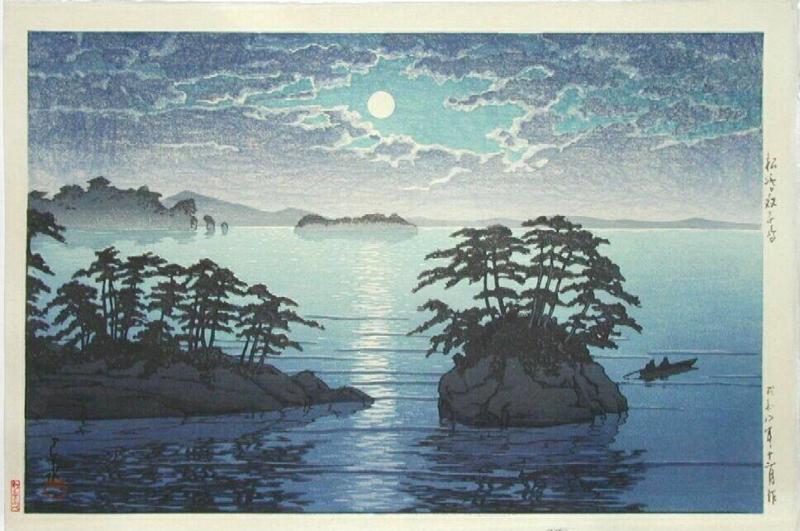

Wabi can mean melancholic, unassuming, solitary, calm, still, impoverished, or unpretentious. The classic scene of wabi is a landscape with an abandoned fisherman’s shack. Sabi can mean ancient, mature, lonely, solitary, and melancholic. It focuses on wear, age, and patina. It’s best to think about a wooden tool or piece of wooden furniture that has been worn smooth from use (Covello, 1995). The words combine to describe the feeling of humble dignity some objects possess due to their age and state of being forgotten.

I’ve felt wabi-sabi long before I’ve encountered the word. I love ruins, and I don’t use the word love lightly in that statement. I feel a deep attraction for the forgotten and overlooked and broken perfection of a crumbling shack in the woods or a hammer left in a field or a moldering book forgotten in a bookstore. The mix of sadness and sweetness and respect fills me with joy. That’s the thing about wabi-sabi, its a mix of contradicting emotions and appreciation. Sadness toward the isolated forgetting of a once-appreciated object. Joy toward its beautiful, broken perfection. Calmness toward its solitude.

Wabi-sabi comes from Zen’s fusing of opposites, removing the distinction between the beautiful and the ordinary (Kondo, 1985). Wabi-sabi is best considered as the realization that nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect. At the same time, the realization also builds the opposites: everything lasts in its unlasting, everything is finished in its unfinishing, everything is perfect in its imperfections. A house may crumble, but its memory and its unseen impact lasts; the house’s change is never finished as it crumbles and changes form. A crumbling house is perfectly imperfect–it is what it is. At its core, wabi-sabi is the acceptance and appreciation of reality as it is. It doesn’t seek to change the nature of reality or deny the truth of impermanence. Instead, it embraces it.

Living a Wabi-sabi Life

Although wabi-sabi is an aesthetic, we can apply its idea to our lives. After all, we are all broken, crumbling shacks buffeted by ocean winds. You see, modern life has taught us that we have to be painted, polished, shiny, young, and new. But that message denies reality. We are aging, breaking, scarring, wrinkling, failing, and imperfect. Modern messages also deny the fact that we are constantly changing in viewpoints as we experience life. Flip-flopping is the negative political term, but wabi-sabi embraces change. It’s okay to change your mind, just as a shack will crumble under the rain. Yet, the end jumble is a step closer to what is true. Changing your mind results from living.

Although wabi-sabi is an aesthetic, we can apply its idea to our lives. After all, we are all broken, crumbling shacks buffeted by ocean winds. You see, modern life has taught us that we have to be painted, polished, shiny, young, and new. But that message denies reality. We are aging, breaking, scarring, wrinkling, failing, and imperfect. Modern messages also deny the fact that we are constantly changing in viewpoints as we experience life. Flip-flopping is the negative political term, but wabi-sabi embraces change. It’s okay to change your mind, just as a shack will crumble under the rain. Yet, the end jumble is a step closer to what is true. Changing your mind results from living.

So what would a wabi-sabi life look like? Much like your life now, only with a little more awareness. Okay, I know that isn’t helpful. That’s the thing about any idea from Zen, it’s more about paying attention than forcing change. After all, we can’t change something without first seeing what needs change. And often just seeing what needs changed, changes it. I’ve seen that with myself. I’ve changed without making an effort to change. In fact, that’s how we all work. Change happens on its own without our effort. Of course, this undirected change isn’t always beneficial. That’s where awareness comes in. It allows us to direct the process of change.

In any case, a wabi-sabi life entails:

- Realizing your imperfections as perfections

- Embracing solitude

- Cultivating calmness

- Accepting the reality of aging

- Accepting melancholy

You are perfect as you are. It sounds saccharine, but just as the rust spot on a hammer is perfectly imperfect, you too are the same. The concept of perfect isn’t rooted in reality. It is some idea, some “should,” that some other person came up with. Society eventually agreed that perfect constitutes a certain “this” that rarely matched reality,

Solitude is something that many people struggle with accepting. After all, modern society has a bias toward extroversion. However, it is only through solitude that you can come to truly know yourself. If you are with other people, they will color your view. In fact, they will continue to color your view even when you are alone until you learn to quiet them and sit with yourself. Too much solitude isn’t healthy either, but right now, people skew toward too much socialness. Cultivating calmness ties together with solitude too. You can only be calm when you accept yourself and know yourself.

Solitude is something that many people struggle with accepting. After all, modern society has a bias toward extroversion. However, it is only through solitude that you can come to truly know yourself. If you are with other people, they will color your view. In fact, they will continue to color your view even when you are alone until you learn to quiet them and sit with yourself. Too much solitude isn’t healthy either, but right now, people skew toward too much socialness. Cultivating calmness ties together with solitude too. You can only be calm when you accept yourself and know yourself.

Media makes us believe we should always be young and happy. Reality, well, is different. Yeah this sounds obvious but acceptance is different from knowing. You and I have to die. We will have good days and bad days. We will feel depressed and sad. That is reality. Feeling melancholy doesn’t mean you have to suffer. Suffering happens when our ideas of how things should be clashes with how they truly are. Accepting reality helps curb suffering by throwing away our ideas of “should.”

Simplicity sits at the core of the wabi-sabi aesthetic. Simplicity centers on perspective more than possessions. Having less stuff does tend to create a simpler life, but so does wanting what you already have. Simplicity doesn’t mean you throw out what you own. Rather, it means you appreciate what you own and accept how objects age and break. It means doing less and striving for less. When you appreciate objects, you need fewer. Of course, I’ve read old Japanese accounts from tea masters lamenting how their patrons collected wabi-sabi teapots and miss the point of wabi-sabi in the first place.

Wabi-sabi isn’t a life style like Zen. It’s an aesthetic, a feeling. But it can be a perspective that helps you live a more appreciative, peaceful life. The most important aspect of wabi-sabi is the realization that imperfection is perfect. Imperfection–never meeting anyone’s “shoulds”–characterizes life. Accepting this goes a long way to making life better, and wabi-sabi encourages us to see the beauty in this. It works against media messages and the messages of advertising. Next time you see a broken hammer, rusting car, or a crumbling house, stop for a moment and pay attention to it. Notice the feelings it generates in you. Appreciate its patina and take the experience of wabi-sabi with you.

References

Covello, Vincent (1995). The Japanese art of stone appreciation: suiseki and the aesthetic pursuit of wabi sabi, shibui, and yugen. Arts of Asia. 25 (1). 95-100.

Kondo, Dorinne (1985) The Way of Tea: A Symbolic Analysis. Man. 20 (2). 287-306.