Despite how odd anime and manga appears, with their fan service and visual language and odd stories, they’re tame compared to Japan’s literature. I spend a fair bit of time beating up on fan-service, but fan-service doesn’t compare to shunga and the woodblock print books from the Edo period.

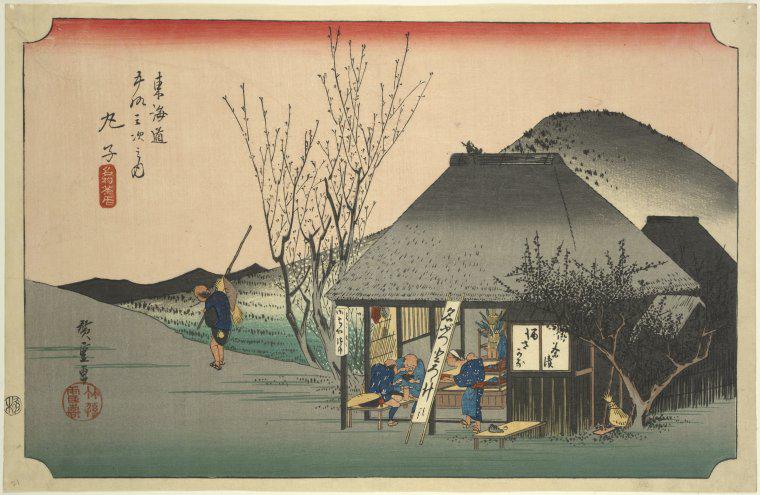

Manga has roots in ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world. These mass-produced woodblock prints were popular during the Edo period (also called to Tokugawa period). Ukiyo-e depicted actors, geisha, landscapes, and other subjects. And they all had a story. In fact, many of them had risque stories. Let’s look at a few examples.

The cloth on the windowsill not far from the cat has a pattern that people in the Edo period would’ve understood as belonging to a certain man. On the floor is a woman’s hairpin and clothing. Also, the view from the window places the scene in a pleasure district. While the scene features a cat, it really depicts a man’s evening with a woman of the pleasure district. Let’s look at another example of this subtle story telling.

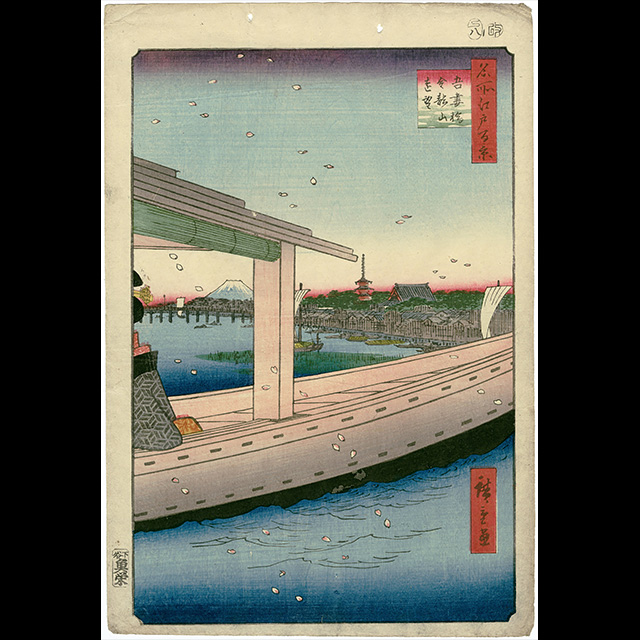

In this print, we partially see a woman riding on a boat with cherry blossom petals blowing in the wind. The direction of the blossoms–if you look closely they blow in 2 directions–reveal the location of the boat. The blossoms blow from a grove of cherry trees off the left side of the frame. The woman also isn’t traveling alone. A man sits off-frame. We know this because of her out-on-the-town dress and the size of the boat. Of course, the question arises, who are they? I’m sure the print has more hints, but I’m not versed well enough to tease out the particulars. That’s one of the problems with stories like this, they are bound to their time periods.

This subtle way of telling a story came from the Edo period idea of sophistication, or iki. Iki tried to engage the viewer rather than merely dictate to the viewer. The idea of sophistication trusts the reader or viewer to fill in the gaps, even if the conclusions differed from the creator’s intent. That could include recognizing people in the story through a symbol or design associations. After all, nobles had family crests and patterns. Likewise, the rich adapted their own symbols.

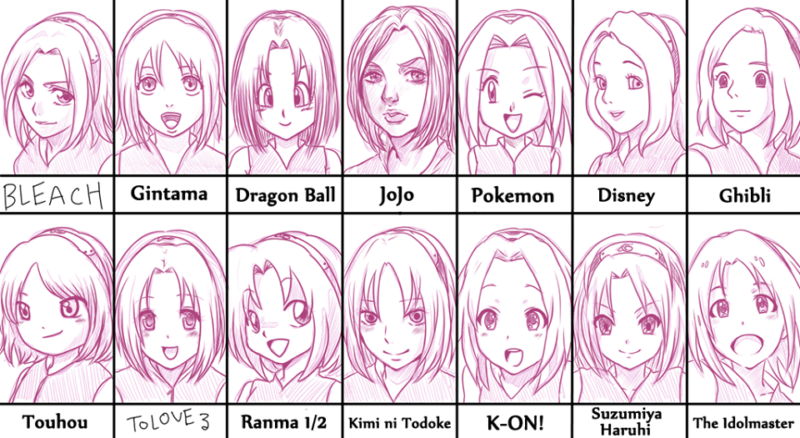

Anime and manga’s visual style plays into iki. The spareness and templated visuals allow the viewer to fill in the gaps. In fact, if you look at woodblock prints, you can see where anime’s visual style originated. Most people in woodblock prints follow designs common to the artist’s school. While many online reviewers dislike how incestuous anime and manga’s style has become, they fail to understand the connection to these prints. Despite the similarities of the styles, sophisticated viewers can still pick out the subtleties that mark different studios. Woodblock print artists can be picked out using the same methods. Utagawa designs look different from Hokusai designs.

Of course, iki is a bit obscure for us today, but the prints shows how tantalizing hints of sexuality has long been a part of Japanese culture. Of course, anime isn’t as subtle, but in most genres they prefer hinting over showing. That’s one reason why panty fan service is so common. It hints at sexuality and personality.

But really, panty fan service is tame compared to Edo period shunga. Shunga were sexual woodblock prints that people compiled into sex-manuals. Of course, some of these prints advertised services or women of the red-light districts. Other prints acted like today’s gossip magazines. They featured prominent people of the time–actors and the like–in sexual situations with other popular people. New wives often received shunga as bridle gifts. The manuals tried to educate them in how to keep their husbands somewhat faithful in an age when red-light districts were accepted and common. Even today, you can find manga dedicated to educating about sexuality, but shunga focused more on techniques than general knowledge.

Shunga (The link takes you to a page I compiled. They are explicit.) are quite overt, detailing all the male and female bits. Time to time, they appeared as folded inserts for novels. Hentai descended from shunga, but the woodblocks engaged the imagination of the viewers by telling an illicit story. Hentai, like all modern porn, leaves little room for the imagination. As any romance reader can tell you, imagination makes a scene more engaging. What isn’t seen excites the mind more than what is seen.

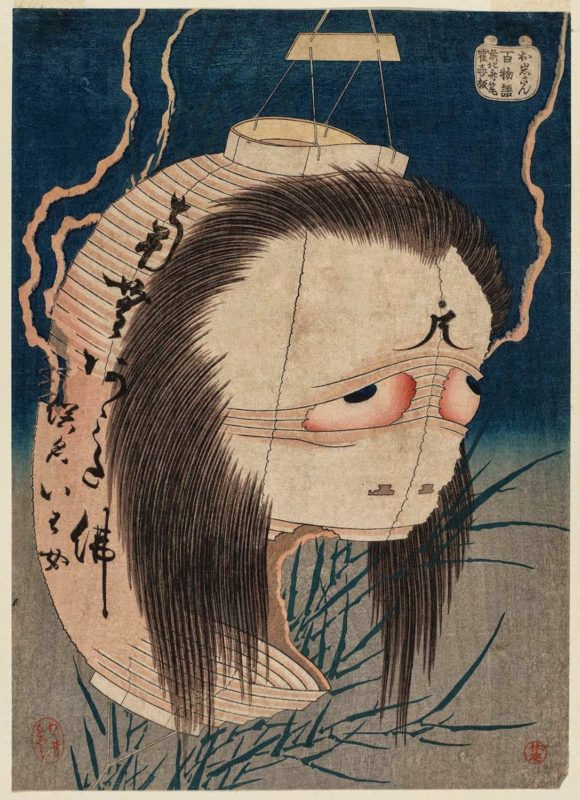

Beyond visual appearances, the stories of manga and anime are pretty tame compared to Japanese folklore. Anime can get quite strange. Just check out FLCL’s visuals. Yet, anime doesn’t approach the weirdness of traditional Japanese literature. For example, do you know where the phrase “giving people the stink eye” came from?

Once a samurai was traveling in the woods when he encountered a farmer blocking his path. The samurai demanded the farmer move as was proper to the man’s lower station.

“I was here first,” the old farmer said.

The samurai gripped his sword. “I can rightly strike off your head. It’s your final warning. Move.”

The old farmer cackled and turned around. He bent over and promptly dropped his drawers, exposing his buttocks at the samurai. He smacked his tanned flank and laughed.

In a rage, the samurai stepped forward to strike down the ingrate, but he happened to look down and saw a brown eye appear from the center of the man’s buttocks. The sight withered the samurai’s courage, and he fled.

My rendition of the story lacks the charm of the versions I’ve read. Kappa stories, as another example, tell of a creature that wants to suck out a person’s shirikodama or “small anus ball.” Kappa would wait for someone to squat at a body of water and reach up the victim’s rectum to pull out the anus ball, killing the person in the process. They would also drag people into water to drown them while sucking at their rectum.

We have to remember that stories resonate with their times, even mass-produced stories like anime. Woodblock prints were mass produced in the Edo period, and they catered to their times. Today, we can’t look at a print and immediately see the story the print suggested. Anime and manga tell their stories more overtly, which certainly helps their accessibility. Their international, mainstream status has diluted some of their Japanness.

As I speak of tameness and Japanness, I speak as a Westerner. Folk stories are just folk stories, and Western versions will look as strange to an outsider as Japan’s look to us. I’ve spoken with many concerned parents as a librarian. They find anime strange and troubling with how “out there” the stories and content are. For those of us immersed in it, we don’t think about anime’s oddness. Anime’s creativity and boldness continues to surprise me, particularly with the focus on sometimes awkward everyday scenes. The parents don’t see the creativity, only the oddness. In particular, they focus on the sexuality of anime. They worry about fan service and the like. But anime’s sexuality is tame compared to the widely available woodblock prints of the Edo period. Much of it comes to a culture clash. American culture retains its Puritan base whereas Japan has a history of sexual acceptance. Anime has achieved mainstream status while still retaining much of its Japanness. Some of the cultural differences won’t disappear, but understanding where anime comes from (and how tame it actually is) will help ease some of these parental concerns.