Ukiyo-e, manga’s great-great-great-great-great grandmother, gives us a window on the Edo Period of Japan. Four-hundred years in the future, our descendants may look upon today’s manga as we do ukiyo-e. That’s something to think about!

Ukiyo-e, Merchants, and the Red Light District

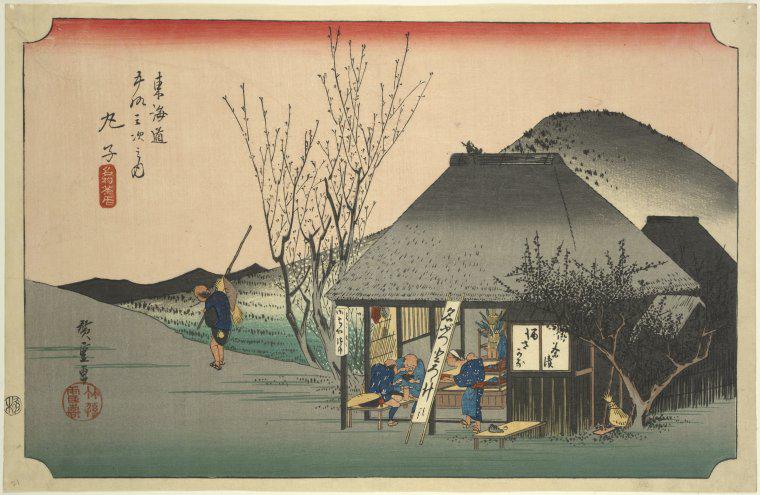

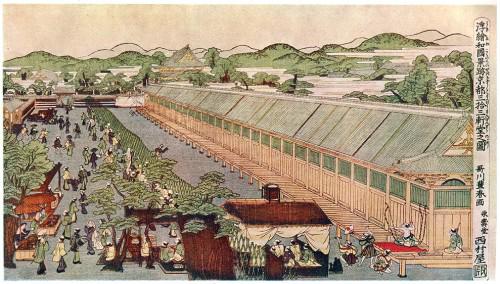

Ukiyo-e, or woodblock prints, used carved wooden blocks to print images on paper. Their inexpensive price and mass production made them the fashion magazines, pin-ups, sex guides, flyers, advertising, and manga of Japan between 1615 and 1868. Ukiyo-e translates to “images of the floating world.” Ukiyo in Japanese Buddhism meant either “sad world” or “floating world” and referred to the troubling, suffering state of humanity. The pleasure districts of the Edo Period represented a slice of suffering and a reprieve from it at the same time (Fleming, 1985). These districts offered everything from gambling and prostitution to teahouses with their cultured geisha. Theaters hosted kabuki and popular puppet shows. These districts were walled off from the rest of the city and lit with red lanterns, literal red light districts. They became centers for dance, fashion, and music. Prostitution and gambling were regulated by the Shogunate, the central government. The regulation allowed families mired in debt to legally sell their female members to the districts so they could work off family debt. Women could also be sentenced to work in the districts. Few courtesans could pay off her debt and become independently wealthy. Geisha–who shouldn’t be confused with prostitutes– provided a better chance. However, both geisha and high-end courtesans were expected to be educated. For many women, this was the only way to access education.

Ukiyo-e also became the primary way for the merchant class to be heard. During this period, merchants threatened the samurai class. Merchants controlled more wealth than the samurai class. This threatened the Shogunate. In response, the Shogunate shuffled Japan’s social hierarchy and placed merchants near the bottom, stripping the class of political power and safeguarding the samurai from their influence. Without official political channels to put wealth into, merchants began to channel their wealth into theater, music, and art–places where they could still be equal to the upper classes. Ukiyo-e became their “in” with the samurai and other classes. The inexpensive production method and affordability allowed merchants to direct taste in fashion, culture, entertainment, and more (Library of Congress, n.d.).

Ukiyo-e artists embraced the pop culture of the time. Geisha, courtesans, and kabuki actors were common subjects. These were the Edo Period version of headshot photography. Called bijin-ga, or beauty portraits, these prints appeared in guidebooks, books on etiquette, and as advertisements (Munro, 2008). Many prints acted as advertising or pin-ups. Later ukiyo-e took to portraying tourist locations around Edo and other landscapes. Ukiyo-e were printed in single sheets and compiled into books call ehon (Library of Congress, n.d.).

Censoring Ukiyo-e

The Shogunate wasn’t ignorant of the power ukiyo-e had for conveying ideas. They imposed strict regulations as to what could be printed. The court forbade publishing anything of “political subversion, sexual and social [im]propriety and excessive luxuriance contrary to the frugal spirit of Neo-Confucian morality” (Thompson, 1991). In 1804, the Shogunate tried several artists, writers, and publishers for their representation of the 16th century general Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Hideyoshi was the guy who decided to regulate and separate prostitution and gambling from the rest of Edo. He wanted these districts to be a place for merchants to blow their money and reduce their hold on the samurai class. Many samurai were in debt to merchants. The Shogun liked the premise, but not the application, so he had the districts walled off. This increased their allure. After all, what we don’t see attracts us. Among the artists arrested was Kitagawa Utamaro, one of the most popular ukiyo-e artists of the time. The team had published a book called Ehon Taikoki, a biography of Hideyoshi 7 years before their arrest.

The Shogunate wasn’t ignorant of the power ukiyo-e had for conveying ideas. They imposed strict regulations as to what could be printed. The court forbade publishing anything of “political subversion, sexual and social [im]propriety and excessive luxuriance contrary to the frugal spirit of Neo-Confucian morality” (Thompson, 1991). In 1804, the Shogunate tried several artists, writers, and publishers for their representation of the 16th century general Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Hideyoshi was the guy who decided to regulate and separate prostitution and gambling from the rest of Edo. He wanted these districts to be a place for merchants to blow their money and reduce their hold on the samurai class. Many samurai were in debt to merchants. The Shogun liked the premise, but not the application, so he had the districts walled off. This increased their allure. After all, what we don’t see attracts us. Among the artists arrested was Kitagawa Utamaro, one of the most popular ukiyo-e artists of the time. The team had published a book called Ehon Taikoki, a biography of Hideyoshi 7 years before their arrest.

Odd the Shogunate waited 7 years before bringing the artists to court, isn’t it? The government forbade the publishing of anything involving Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first Tokugawa shogun, and his family. Hideyoshi was fair game, and other biographies were published before 1804. So why were Utamaro and his colleagues singled out? The problem was how the values Hideyoshi symbolized mixed with the floating world. While he came up with the idea that allowed the floating world to flourish, he was better known as a great general. The shogunate didn’t want one of their historical heroes to become a mere popular figure like just another kabuki actor. The ehon threatened the shogunate’s control over its official history. So Utamaro and his colleagues were tried to curb the trend of portraying warrior families as part of the floating world. The court found them guilty and sentenced them to 50 days house arrest in manacles. The publisher was required to pay heavy fines. The book they published, Ehon Taikoki, was banned and confiscated (Davis, 2007).

Odd the Shogunate waited 7 years before bringing the artists to court, isn’t it? The government forbade the publishing of anything involving Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first Tokugawa shogun, and his family. Hideyoshi was fair game, and other biographies were published before 1804. So why were Utamaro and his colleagues singled out? The problem was how the values Hideyoshi symbolized mixed with the floating world. While he came up with the idea that allowed the floating world to flourish, he was better known as a great general. The shogunate didn’t want one of their historical heroes to become a mere popular figure like just another kabuki actor. The ehon threatened the shogunate’s control over its official history. So Utamaro and his colleagues were tried to curb the trend of portraying warrior families as part of the floating world. The court found them guilty and sentenced them to 50 days house arrest in manacles. The publisher was required to pay heavy fines. The book they published, Ehon Taikoki, was banned and confiscated (Davis, 2007).

Erotic Ukiyo-e

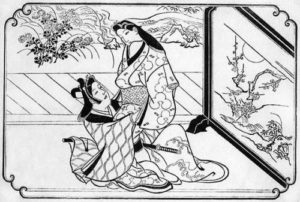

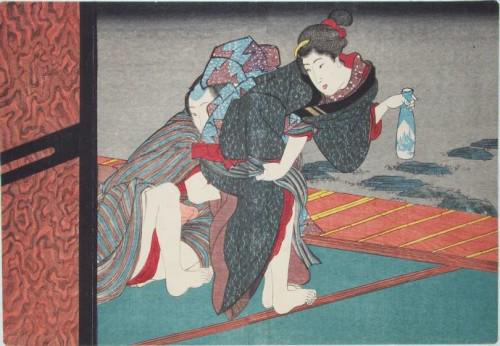

I mentioned how the Tokugawa issued an edict about the limit of ukiyo-e. Well, despite the edict about sexual impropriety, shunga flourished. Shunga is a subgenre of woodblock prints that focused on what went on behind the closed doors of the floating world. Think of shunga as the great-great-great-great-great grandmother of hentai. These explicit prints told stories and served as sex guides. They exaggerated genitals and often had contorted poses. Shunga were produced for both men and women. Many show scenes of lesbian encounters and female masturbation. At the time, the samurai class often segregated genders into quarters within castles. Men were encouraged to visit brothels, but women had fewer options. Male prostitutes were found in theater districts where few women could go (Munroe, 2008). But on the whole, women were housed with other women. In such situations, lesbian romances are sure to develop, and shunga provided guides and stories about such. While samurai men were encouraged to have relations with other samurai men, Japanese literature rarely mentions such relations between women.

I mentioned how the Tokugawa issued an edict about the limit of ukiyo-e. Well, despite the edict about sexual impropriety, shunga flourished. Shunga is a subgenre of woodblock prints that focused on what went on behind the closed doors of the floating world. Think of shunga as the great-great-great-great-great grandmother of hentai. These explicit prints told stories and served as sex guides. They exaggerated genitals and often had contorted poses. Shunga were produced for both men and women. Many show scenes of lesbian encounters and female masturbation. At the time, the samurai class often segregated genders into quarters within castles. Men were encouraged to visit brothels, but women had fewer options. Male prostitutes were found in theater districts where few women could go (Munroe, 2008). But on the whole, women were housed with other women. In such situations, lesbian romances are sure to develop, and shunga provided guides and stories about such. While samurai men were encouraged to have relations with other samurai men, Japanese literature rarely mentions such relations between women.

The Making of a Woodblock Print

Just like mangaka need help creating their work, ukiyo-e artists needed a team. It took 4 people to make a print. The publisher coordinated everyone and handled marketing. The artist dreamed up the designs and drew them in ink on paper. A carver broke the design into patterns that were carved into wood blocks. The number of blocks used ranged from 10 to 16, depending on the number of colors and complexity of the drawing. And a printer managed the ink and handmade paper (Library of Congress, n.d.). The artist receives most of the recognition, much like the front-man in a band. Each member of the team was highly skilled in their piece of production. The printer often made their inks and paper from raw materials, for example.

The carver cut the negative of the design: the lines and areas to be colored were raised. The rest was carved away. Each color required a different block that had to be perfectly aligned. Paper made from the inner bark of the mulberry tree would be laid on the blocks and rubbed to transfer the ink (Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d.). The blocks were used until they wore out.

The mass production of these prints makes them hard to preserve. Paper and silk are vulnerable to Japan’s variable weather. The inks change color when exposed to light for long periods (Fleming, 1985).

How to Read Ukiyo-e

Beyond the obvious Japanese writing, ukiyo-e has to be read to be understood. The Edo Period had a host of pop culture symbols that allowed a print to tell a story. For example, eyebrows matter. Married women shaved their eyebrows. So this lady on the left is single! Notice how she shows off the nape of her neck? Well, that was…is… an erogenous zone for Japanese men. So this print has voyeuristic elements. We are looking in on a young woman as she applies her makeup, something few men would witness. Think of it as peaking in on a lady as she showers. Ukiyo-e often showed everyday actions like this with a twist.

Beyond the obvious Japanese writing, ukiyo-e has to be read to be understood. The Edo Period had a host of pop culture symbols that allowed a print to tell a story. For example, eyebrows matter. Married women shaved their eyebrows. So this lady on the left is single! Notice how she shows off the nape of her neck? Well, that was…is… an erogenous zone for Japanese men. So this print has voyeuristic elements. We are looking in on a young woman as she applies her makeup, something few men would witness. Think of it as peaking in on a lady as she showers. Ukiyo-e often showed everyday actions like this with a twist.

Like eyebrows, the importance of ukiyo-e is in what is missing. The artists focused on the positive aspects of the floating world. You do not see the lowest levels of prostitutes. Women are all painted in idealized way with few individual characteristics or blemishes. Ukiyo-e, like the floating world the prints reflected, represented ideals of feminine beauty. They didn’t represent individual women. The omission of individual women attempts to capture the image of fleeting forever the floating world wrapped around itself. It weaves a fantasy.

The floating world influences much of Japanese sexuality today. Japanese sex culture focuses on fantasy more than experience (Bourdain, 2014). Maid Cafes descend from the red-lit fantasy world. Hentai and other erotica descends from this period.

Ukiyo-e and Manga

Ukiyo-e and manga share similar art styles. Flat coloration with prominent outlines. Ukiyo-e was the popular media of the time, entertaining people and telling stories. The cheap cost of ukiyo-e allowed it to spread throughout the Edo Period. Manga does the same today. It is relatively inexpensive and is a part of Japanese popular culture. Ukiyo-e experimented with ways of representing motion and emotion with minimal lines. The prints laid the framework for all the genres and themes we see in manga: erotica, macabre, humor, historical stories, current events, and slice of life. Manga inherited the free thinking and experimentation of the floating world.

Ukiyo-e is a look at the lost floating world of dreams and suffering. The dreams of pleasure, conversation, and culture came at the price of the women and men sold into its work. Ukiyo-e freezes moments, people, and concerns in ink.

References

Bourdain, A. (2014). Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown: Tokyo. http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1401/25/abpu.01.html

Davis, J. (2007). The trouble with Hideyoshi: censoring ukiyo-e and the Ehon Taikoki incident of 1804. Japan Forum 19 (3) 281-315.

Fleming, S. (1985). Ukiyo-e Painting: An Art Tradition under Stress. Archaeology. 38 (6) 60-61, 75.

Library of Congress. The Floating World of Ukiyo-e. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/ukiyo-e/intro.html.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm.

Munro, M. (2008) MasterClass: Understanding Shunga, A Guide to Japanese Erotic Art. London: Turnaround.

Thompson, Sarah E. and Harootunian, H. D. (1991)Undercurrents in the Floating World: Censorship and Japanese Prints, New York: The Asia Society Galleries.