Most people think of Basho and haiku when they think about Japanese poems. Japanese poetry encompasses more than lovely nature images. The word literature conjures, at least for me, feelings of stuffiness and boredom. It’s easy to forget that what we deem literature, that is, writing representative of a time period, was the love poems and goodbyes of people. Japanese poetry contains praise for sake, death poems, children’s songs, and even jokes like this one:

Letting rip a fart —

It doesn’t make you laugh

When you live alone.

and

‘She may have only one eye

But it’s a pretty one,’

says the go-between.

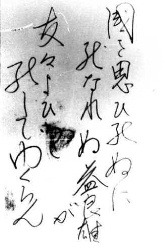

All of the poems I cite in this article comes from The Penguin Book of Japanese Verse translated by Geoffrey Bownas and Anthony Thwaite (1964). The book covers a range of time periods, from Heian to Meiji. It even has some folktales. However, the section dedicated to frontier guards and their families struck me. Around the mid-eighth century, Japan expected an invasion from mainland Asia. Men were sent to southern Kyushu for three years. Imagine a three year separation from your significant other with only letters to remain in touch. These poems are tanka, a style of poetry that uses a syllable pattern of 5-7-5-7-7. For me, the pattern isn’t important. Rather, I focus on the story behind these poems and the feelings behind them. Remember, this was an age where illness and death was a reality. Some of the poems could well have been final goodbyes. Fortunately, we have the names behind many of these poems. These poems too are direct. You don’t have to understand the layers of meaning behind the imagery like you do with haiku and some other poems. These people weren’t common folk, but they also weren’t literati as we often see. Instead, we get a raw picture of sons leaving parents and of husbands leaving families.

Poems Remembering Parents

Behind my parents’ house

Grows the centi-grass.

Live a hundred years

until I shall come back.

–Ikutamabe Tarukuni

In the scramble to get away —

Like the waterfowl taking off —

I came not saying a word

To my mother and father,

And now I regret it.

–Udobe Ushimaro

‘I shall forget,’ I said,

Marching over moor and mountain,

I tell you now, my parents,

I never can forget.

–Akinoosa Obitomaro

Staying here at home

Longing for you? No!

Would that I could be

The broad sword you wear

And guard your body.

–the father of Kusakabe Omininaka

Poems Remembering Wives

The dreadful order

I have received.

From tomorrow

With the grass I sleep,

No wife being with me.

–Mononobe Akimochi

That wife of mine

Must love me much:

In the water I drink,

Even, her shadow.

I could never forget her.

–Wakayama Mimaro

O That I’d had

A moment to paint

A picture of my wife.

Looking at it on the journey,

I could have seen and thought.

–Mononobe Furumaro

You stood at a bend

In that fence of reeds,

Your sleeve sodden with tears.

So I picture you.

–Osakabe Ataechikuni

While the leaves of the bamboo rustle

On a cold and frosty night,

The seven layers of clobber I wear

Are not so warm, not so warm

As the body of my wife.

–unknown

Poems from Wives

The horse is loose

In the mountain pasture.

I couldn’t hobble him for life,

So I’ll have to send you off

On foot over Tama Brow.

— Ojibe Kurome, wife of Kurahashibe Aramushi

‘Whose man goes

As frontier guard?’

I hear them ask

With no anxiety —

And how I envy them.

–unknown wife

Poems Exchanged Between Husband and Wives

My bright mirror

Means nothing to me

When I see you

On foot, toiling on

–unknown wife

If I buy a horse,

You must go on foot.

Even should we tramp rough rocks,

I would rather walk with you.

–by her husband

As you can see, these poems are direct and lack the flowery layers we usually associate with Japanese poetry. They contain a sense of loss, of sadness these three year stints caused. The exchange between husband and wife above is especially touching. The husband would rather walk beside his wife than ride a horse, as was proper for his station as a guard. Parents pine after their sons, and sons have regrets. Distance and time often strip away our tendency to take people for granted. These poems reflect that.

History often feels faceless. It’s taught around dates and events. We lose the human story, and that story is what makes history. These poems offer a glimpse at this human story. We see a soldier remembering the sight of his wife crying as he left. We have a son regretting his rush to leave. This is history. The trajectory of history comes from the sum of these stories. Napoleon, for example, couldn’t have marched across Europe without the unknown soldiers in his army and the even less-thought about people who grew the food and sewed the uniforms. Behind the “Great Man” idea is a confluence of unknown people who support the shakers of history. The voices of women are particularly lost in history. This wasn’t always malicious. Time is cruel to records, and the majority of people who lived in the past weren’t literate. The Great Man theory of history only sees the people the records show. Many great men and women who shaped history remain lost because their letters and references are lost or because the written record never existed at all, yet such people have had an influence on the human course. We can’t know what we don’t know, after all. I get excited when lost documents are found for this reason. Sometimes we discover unheard voices, such as the voice of Kodaiin, Hideyoshi’s first and best-loved wife. Even fragments of past voices are important. The poems I shared with you provide a tiny voice for some of these soldiers and wives behind history. If only we had more of these voices.