Each day is a journey, and the journey itself home

Matsuo Bashō was born in 1644 in the town of Ueno to a minor samurai family. While he is best known for his haiku in the West, his travel journals broke ground in Japanese literature. In his teen years, Bashō entered the service of Todo Yoshikiyo, who was also a poet. According to traditional accounts of his life, Bashō worked as part of the kitchen’s staff before being introduced to Kitamura Kigin (1624-1705), one of the best poets of Kyoto at the time. Through Kigin, Bashō was able to become a professional poet and move to Edo (Carter, 1997). He began as a haikai poet. A haikai is a type of poem made of linked verses (Norman, 2008). Bashō went by many names before settling on the one we know: Kiginsaku, Toshichiro, Tadaemon, Jinshichiro, and Munefusa. His first haiku was published under the name of Tosei, which translates to “green peach.” The name pays homage to Bashō’s favorite Chinese poet Li Po (or “white plum”) (Norman, 2008). Bashō wrote over 1,000 haikus in his lifetime. Unlike other poets of his time, Bashō focused on the everyday moments. He tried to capture the moment a bird took wing or a frog jumped (Biallas, 2002). He never claimed there was a single way to write good haiku. Instead, he argued a good poem came from a flash of insight and jotting it down immediately (Heyd, 2003).

Matsuo Bashō was born in 1644 in the town of Ueno to a minor samurai family. While he is best known for his haiku in the West, his travel journals broke ground in Japanese literature. In his teen years, Bashō entered the service of Todo Yoshikiyo, who was also a poet. According to traditional accounts of his life, Bashō worked as part of the kitchen’s staff before being introduced to Kitamura Kigin (1624-1705), one of the best poets of Kyoto at the time. Through Kigin, Bashō was able to become a professional poet and move to Edo (Carter, 1997). He began as a haikai poet. A haikai is a type of poem made of linked verses (Norman, 2008). Bashō went by many names before settling on the one we know: Kiginsaku, Toshichiro, Tadaemon, Jinshichiro, and Munefusa. His first haiku was published under the name of Tosei, which translates to “green peach.” The name pays homage to Bashō’s favorite Chinese poet Li Po (or “white plum”) (Norman, 2008). Bashō wrote over 1,000 haikus in his lifetime. Unlike other poets of his time, Bashō focused on the everyday moments. He tried to capture the moment a bird took wing or a frog jumped (Biallas, 2002). He never claimed there was a single way to write good haiku. Instead, he argued a good poem came from a flash of insight and jotting it down immediately (Heyd, 2003).

Let me digress a moment. Haiku is a 19th century contraction of hokku no haikai. A haiku is a 3 line poem that follows a specific pattern of ji-on, or symbol-sounds. Ji-on are made up of a single vowel or a consonant + vowel. Haiku lines follow this pattern: 5-7-5. Let’s look at an example from Bashō.

| Autumn deepens— The man next door, what does he do for a living? | aki fukaki tonari wa nani o suru hito zo |

I highlighted every symbol-sound to help you see how the 5-7-5 rule works. Haiku doesn’t try to rhyme. It focuses on the symbol-sound pattern and its imagery. Haiku often use a word or expression (called a ki-go) to pin down the time of the year. This sets the mood of the poem. Autumn, for example, has a lonely feeling. Ki-go act as shorthand to convey feelings, ideas, or meaning in as few words as possible….if you understand what feelings, ideas, or meanings are associated with the ki-go. Weather conditions and animals can act as ki-go. Weather conditions and animals have strong associations with certain seasons. Such as rain showers and spring here in the United States. Before Bashō, haikai poetry fixed on the tastes of the courtly elite or funny topics that appealed to the merchant class. Bashō’s poetry focused on common, everyday experience. Basho defined what we know of as haiku.

In 1680, Bashō gave up his practice in a way that amounts of professional suicide. He gave up his professional status and moved outside of Edo. He wrote this poem the same year:

On a bare branch

A crow has settled down to roost.

In autumn dusk.

His students followed him and built him a home. They also gave him basho trees (a type of banana). He began writing under that name, and it stuck with him: Basho. During this time, he studied Zen but struggled with spiritual beliefs. In 1682, his house was caught in the fire that burned most of Edo (Norman, 2008). He mourned the event:

Tired of cherry,

Tired of this whole world,

I sit facing muddy sake

And black rice.

Part of the reason he moved was to avoid his fame, but people still followed and pestered him. He had to resort to locking his gate to escape. Of course, he wrote about it:

Only for morning glories I open my door—During the daytime I keep it tightly barred.

Despite people calling him a master poet, Basho felt dissatisfied with his writing. Many times he wanted to give it up altogether. He called his writing “mere drunken chatter, the incoherent babbling of a dreamer” (Biallas, 2002). His discontent seemed to be one reason why he decided to take to the road starting in 1684. His first journal, Journal of a Weather-Beaten Skeleton, captures the difficulty of travel at the time. That hardship becomes a reoccurring theme in his later journals. He traveled several times between 1687-1688 and wrote about the experiences in Kashima Journal and Manuscript in a Knapsack. The journals combined prose and haiku, a combination called haibun (Heyd, 2003; Norman, 2008). He often focused on little things he observed while on the road:

Stillness—

Piercing the rock

The cicada’s song.

It is hard to us to imagine the difficulty of travel at the time. People traveled on foot with few rest stops and exposure to wind, rain and lice. Bashō even wrote about the trouble lice caused him: “Shed of everything else, I still have some lice I picked up on the road—Crawling on my summer robes.” He wrote about how rice-planting songs were a part of poetic tradition and wrote about the refinement of people found in rural villages. At the time, only those who lived in cities and belonged to the upper classes were thought of as refined. Equating country farm songs with samurai class poetry was also a break in the thinking of that time.

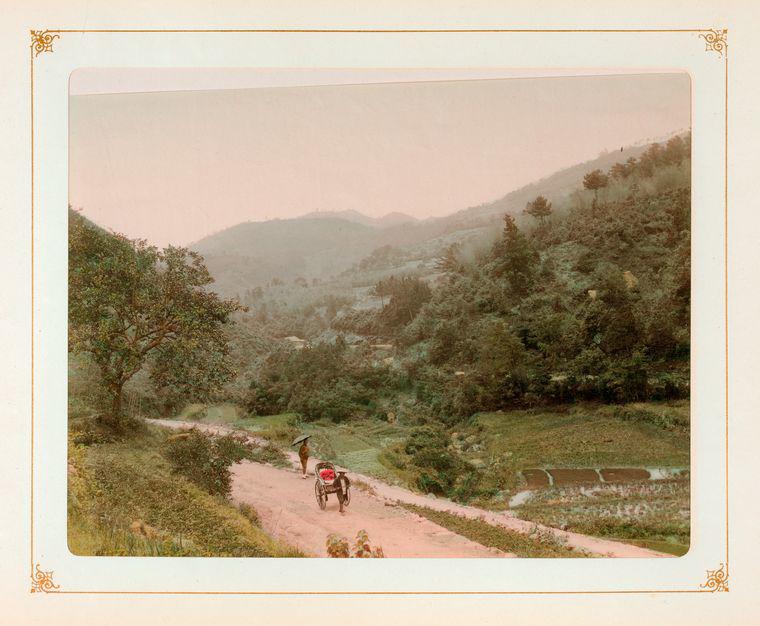

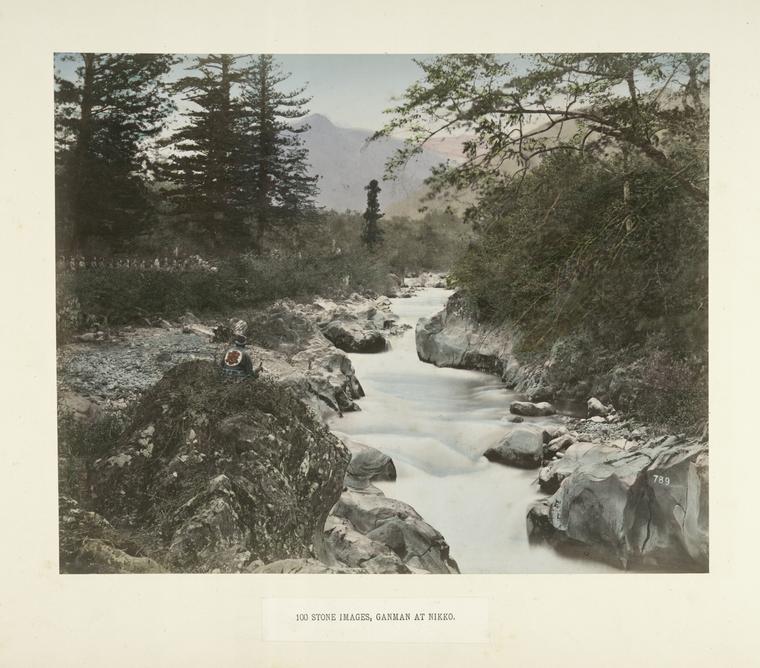

In his mid-40s, Basho grew tired of his fame. Despite his frail health, he decided on taking a pilgrimage to locations important to Japanese religious, literary, and military history. In May 1689, he set out with his friend Sora, a backpack, writing materials, and a few changes of clothes. We walked for 5 months, during which he penned his masterpiece, Narrow Road to a Far Province. The book spoke of a spiritual journey while Basho made his living on the road as a teacher (Carter, 1997). The entire journey involved walking 1,200 miles through some of the roughest terrain of Japan. Some of the roads were little more than trails.

Here are excerpts from Narrow Road:

The months and days are the travelers of eternity. The years that come and go are also voyagers. Those who float away their lives on ships or who grow old leading horses are forever journeying, and their homes are wherever their travels take them. Many of the men of old died on the road, and I too for years past have been stirred by the sight of a solitary cloud drifting with the wind to ceaseless thoughts of roaming.

Last year I spent wandering along the coast. In autumn I returned to my cottage on the river and swept away the cobwebs. Gradually the year drew to its close. When spring came and there was mist in the air, I thought of crossing the Barrier of Shirakawa into Oku. I seemed to be possessed by the spirits of wanderlust, and they all deprived me of my senses. The guardian spirits of the road beckoned, and I could not settle down to work.

I patched my torn trousers and changed the cord on my bamboo hat. To strengthen my legs for the journey I had moxa burned on my shins. By then I could think of nothing but the moon at Matsushima. When I sold my cottage and moved to Sampû’s villa, to stay until I started on my journey, I hung this poem on a post in my hut:kusa no to mo

sumikawaru yo zo

hina no ieEven a thatched hut

May change with a new owner

Into a doll’s house.

This is the introduction to Narrow Road (Keene, 1996). Moxa was a medical treatment of ground mugwort used to treat or prevent various diseases. Notice how he combines prose with haiku. The next excerpt has Bashō visiting a castle.

The three generations of glory of the Fujiwara of Hiraizumi vanished in the space of a dream. The ruins of their Great Gate are two miles this side of the castle; where once Hidehira’s mansion stood are now fields, and only the golden cockerel Mountain remains as in former days.

We first climbed up to Castle-on-the-Heights, from where we could see the Kitagami, a large river that flows down from the north. Here Yoshitsune once fortified himself with some picked retainers, but his great glory turned in a moment into this wilderness of grass. “Countries may fall, but their rivers and mountains remain. When spring comes to the ruined castle, the grass is green again.” These lines went through my head as I sat on the ground, my bamboo hat spread under me. There I sat weeping, unaware of the passage of time.

His travel journals read a little like modern day travel guides. Bashō visited major military, literary, and religious landmarks. The bits of history help give a context.

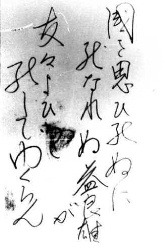

Bashō died in 1694. He remains one of the most important poets in Japanese history, and his work are the first school children learn. His travel journals inspire pilgrimages in an effort to reconnect with a literary tradition. Many anime like Samurai Champloo pull inspiration from a travel tradition Bashō made famous. He wasn’t the first traveling poet, but he stands as one of the best loved. The calligrapher Soryu wrote this epilogue in the Narrow Road:

Once had my raincoat on, eager to go on a like journey, and then again content to sit imagining those rare sights. What a hoard of feelings, Kojin jewels, has his brush depicted! Such a journey! Such a man!

References

Biallas, L (2002) Merton and Basho: The Narrow Road Home. Merton Annual. 15 77.

Carter, S. (1997) On a Bare Branch: Basho and the Haikai Profession. American Oriental Society. 117 (1). 57-69.

Heyd, T. (2003) Basho and the Aesthetics of Wandering: Recuperating Space, Recognizing Place, and Following the Ways of the Universe. Philosophy East and West. 53 (3) 291-307.

Keene, D. (1996) The Narrow Road to Oku.

Norman, H. (2008) On the Poet’s Path. National Geographic. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/02/bashos-trail/howard-norman-text

The haikus,- namely of Mr.Matsuo Jinshichiro as Matsuo Bashō,- calls my deep excitement up in the 1st time in my life,- ɳɭ.

– Mr. Nikita Ludwig, Poetry, Moscow, Greate Russia,-

Sincerely Yours.