Moe has a complex history and meaning. Most people believe it’s a certain type of anime character. Namely, cute, innocent girls with big eyes that do cute things. While moe does deal with this, it’s true definition goes beyond kawaii.

Now, some may wonder why it matters to define anime slang (moe isn’t really slang) precisely. However, anime and its associated terms have a large impact on story telling. In 2012, 60% of the world’s animated cartoons were Japanese anime (Cooper-Chen, 2012). Such a large market means anime terminology will have a widespread influence. Wherever people consume anime, moe and other terms enter people’s awareness.

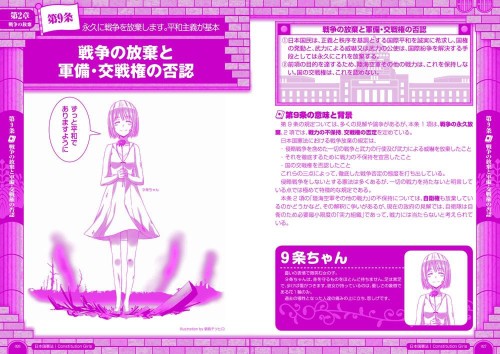

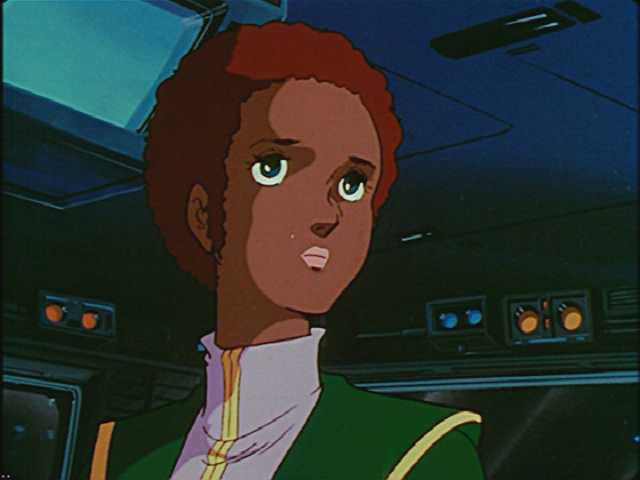

Moe has roots in the 1970s and 1980s. During these decades, artists began creating characters specifically to inspire moe within people (Saito, 2017). It’s a common misconception that moe is just a name for images of cute girls. Moe is an affectionate response to fictional characters. The word comes from the verb moeru which means “to bud or sprout” (Galbraith, 2009). The verb describes how people’s feelings toward characters sprout over time. During the 1980s, marketers began to study which character designs, relationship patterns, and styles of drawing were most likely to create a this feeling of affection (Galbraith, 2009). This is why people confuse moe with a specific style of art or type of character. They are engineered to make you feel moe. Sagisawa Moe, a character from Kyouryuu Wakusei, Takatsu Moe from Taiyou ni Sumasshu, and Hotaru Tomoe from Sailor Moon S make good examples. In fact, the verb moeru combined with an abbreviation of Hatoru Tomoe to give us the word moe. Young girls with large, pupil-less eyes, glossy skin, small (or no) breasts and an innocent personality make the archetype for moe-seeking character design.

Feeling Moe

Feelings of moe vary. For some, it’s a mild sexual arousal and love for a character. For others, it is “the ultimate expression of male platonic love,” and for still others its pure love without sexual components. For many men, moe is an innocent girl that doesn’t “demand masculine excellence” and provides an outlet for nurturing that isn’t available to traditional masculinity. For women, moe is a romance without the “confines of womanhood”–childbirth and responsibility (Galbraith, 2009).

Because moe is an emotional reaction to a fictional character, it varies from person to person. However, it involves a desire for fantasy; it isn’t a desire to realize that fantasy. Fujoshi, or “rotten girls,” provide a good example of these. Fujoshi are women who consume, produce, and reproduce romances inspired by manga and anime. They particularly focus on yaoi.

Women account for the majority of online fan-fiction like yaoi. Yaoi are stories that focus on relationships between androgynous men. People call fujoshi “rotten” because they are attracted to sex fantasies that can’t produce children. However, they embrace that categorization as positive, and most live heteronormative lives. Yaoi “erases the female in fantasy because female-male, or even female-female couples are too close to reality. (Galbraith, 2011). Yaoi focuses on moe. In his interviews, Galbraith (2011) found moe drives yaoi, including its production and shared discussions between fujoshi. These discussions are even called moebanshi or moe talk. These discussions about favorite pairings (such as Link and Sidon, from The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, or Naruto and Sasuke) inspire more writing and conversations. As Galbraith (2011) phrases it:

“Moe communication is about feeling out overlapping desires, or exploring one’s own desires through delving into the desires of others for the same or similar objects.”

People learn about each other through their taste in characters, settings, and situations. It’s a form of self-expression that allows people to connect through their shared moe. Moe allows people to share deeply personal emotions through the shared feeling of fictional affection. The details behind the affection may vary, but moe still allows enough overlap to communicate.

Fujoshi see moe in everything, changing the way they perceive the world and imagine relationships between things. In Galbraith’s study (2011), the fujoshi he interviews saw how a road and a car can be a metaphor for an intimate, moe-inducing dojinshi they had read:

Hachi impulsively decided to use her surroundings as an illustration of the coupling: “Is this road moe? See, it’s virgin, freshly paved, but is doing its best with the cars on top. What if he was trying so hard to please his lover?” Megumi chimed in, “The road is a loser submissive in love with one particular car, the top, who is an insensitive pleasure seeker. In order to win his love, the road agreed to be his sex slave and is now being broken in by the top’s clients.” Tomo seemed convinced—by the creativity if not the concept—and joined Megumi and Hachi in laughter and a chorus of “moe, moe, moe.” The fantasy effectively reenchanted their world, adding a layer of potential to the mundane (the very ground under their feet!) and making the familiar other and exciting.

Fujoshi stand out against otaku in a key way. Otaku are typically people who use fantasy as an alternative for things they want but cannot realize for various reasons. Fujoshi are people who use fantasy for the sole purpose of play. They don’t seek to live through fantasy. Rather, its a place to let imagination, creativity, and emotions frolic without needing to ground them in some sort of reality. The difference is subtle. Both groups focus on fantasy and seek the confluence of affection called moe. They approach the quest from different angles. Waifuism is the otaku quest for moe. Yaoi is the fujoshi quest for moe. Of course, as we’ve seen there are still other paths for finding this comforting set of emotions.

Moe and the Male Gaze

Many people accuse moe as being a part of female objectification: cute girls doing cute things for guys to watch. However, as you can see with the fujoshi, moe extends beyond the sphere of objectification. You could argue fujoshi objectify men through yaoi. But the feelings objectification creates–possession and lust–differ from moe’s feelings. Of course, objectification can overlap with moe just as kawaii culture does. Objectification’s emotions can be confused with affection. People often confuse possession and the resulting jealousy with love. As publishers seek to leverage moe–after all, it sells–we see it mix with objectification more often because the combination pulls a wider, admittedly, male audience. This makes many believe moe centers on the male gaze on women and the gaze of fujoshi on men. But this isn’t the only part of moe. Moe allows men to explore emotional aspects society doesn’t consider a part of masculinity. One Western example, My Little Pony, creates moe, and it attracts men of all ages. However, society is more comfortable with the usual objectifying male gaze than with men exploring their nurturing, protective, and affectionate sides. This familiarity causes the confusion we often see, and the focus on the small overlap of moe-seeking and objectification.

Moe’s Contradiction

On the surface, moe appears a contradiction. It has an element of innocence to it, but it also has adult desires built into it. In our above fujoshi conversation, the innocence of the road changes to a sex slave. Moe often moves along this spectrum because it is pure fantasy. As fantasy, it allows people to project what they want or explore otherwise taboo subjects. For example, Rei Ayanami from Neon Genesis Evangelion is considered a moe-inspiring character. She has an innocence to her that tugs at nurturing and protective feelings. At the same time, these feelings can shift toward sexual desire. English-language media over-emphasizes the sexual components of moe (Saito, 2017). It doesn’t always have to be sexual. Someone who grew up watching Pokemon, for example, may find themselves comforted by their favorite characters. This is moe.

On the surface, moe appears a contradiction. It has an element of innocence to it, but it also has adult desires built into it. In our above fujoshi conversation, the innocence of the road changes to a sex slave. Moe often moves along this spectrum because it is pure fantasy. As fantasy, it allows people to project what they want or explore otherwise taboo subjects. For example, Rei Ayanami from Neon Genesis Evangelion is considered a moe-inspiring character. She has an innocence to her that tugs at nurturing and protective feelings. At the same time, these feelings can shift toward sexual desire. English-language media over-emphasizes the sexual components of moe (Saito, 2017). It doesn’t always have to be sexual. Someone who grew up watching Pokemon, for example, may find themselves comforted by their favorite characters. This is moe.

Kawaii is often confused with moe because of their overlap. Kawaii, or cute, focuses on the design of characters and objects. Kawaii often creates moe, but it doesn’t always. A cute skirt, for example, may be kawaii, but it doesn’t create moe because the skirt is a physical object. However, if it would become a metaphor or a reminder for a fictional character, it could generate moe. It works in the same way as the road in Galbraith’s example. The road and its cars may create feelings of moe in the girls, but they aren’t kawaii.

Defining Moe

So we’ve come down to creating a single definition for a complex, variable set of emotions. First, moe isn’t a type of image or character design. It’s the emotion inspired by those designs. Second, moe provides an indirect way to express your feelings to others by sharing why you like a character or relationship. It’s a taste in characters, settings, and situations that comes from your experiences and preferences. With this in mind, I’ll offer my definitions:

moe (mo-eh) noun. The feeling of fondness and affection a person feels toward fictional characters or toward any setting or object that reminds the person of those characters.

moe-talk (mo-eh-tôk) noun. The mutual sharing of fondness and affection people feel toward a fictional character that creates a feeling of connection between the people involved in the conversation.

References

Cooper-Chen, Anne (2012), ‘Cartoon Planet: The Cross-Cultural Acceptance of Japanese Animation’, Asian Journal of Communication, 22 (1), 44.

Galbraith, Patrick W. (2009). “Moe: Exploring Virtual Potential in Post-Millennial Japan”. Electronic journal of contemporary Japanese studies.

Galbraith, Patrick W (2011). Fujoshi: Fantasy Play and Transgressive Intimacy among “Rotten Girls” in Contemporary Japan. Signs. 37 (1) 219-240.

Orbaugh, Sharalyn. 2010. “Girls Reading Harry Potter, Girls Writing Desire: Amateur Manga and Shojo Reading Practices.” In Girl Reading Girl in Japan, ed. Tomoko Aoyama and Barbara Hartley, 174–86. London: Routledge.

Saito, A.P. ( 2017). Moe and Internet Memes: The Resistance and Accommodation of Japanese Popular Culture in China.Cultural Studies Review, 23:1, 136-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v23i1.5499

I’m emotionally disabled, so this is confusing AF.

What do you find the most confusing?

Great site – you might check out The Glimpse and its connections with Moe, Otaku and adolescence.

Thanks for the suggestion! I’ll check it out.