What is cute? Actually, the English word “cute” is a poor substitute for kawaii. Kawaii looks to be a simple word, but it hides a host of meanings and implications. Kawaii is more than cute writing, fashion, and kikan fanshii – fancy goods. I will look at the history of kawaii and move toward what makes someone or something kawaii. First, we need to look at the word and all the ideas attached to it.

What does kawaii mean?

The word kawaii comes from the word kawayushi. Kawayushi first appeared in dictionaries during the Taisho era (1912-1926). Kawayushi meant shy, pathetic, vulnerable, embarrassed, loveable, and small. Obviously, kawaii retains much of that meaning. (Kinsella, 1996; Manami & Johnson, 2013).

Kawaii is anything that stirs feelings of love, care, and protectiveness. It is based on the adorable physical features of children and baby animals, but it also has a strong Western influence (Manami, 2013). The large, round eyes that are considered cute are an import from the West (Kinsella, 1996). Kawaii as we know today is a result of the interaction between Japan and the United States after World War II.

Kawaii is anything that stirs feelings of love, care, and protectiveness. It is based on the adorable physical features of children and baby animals, but it also has a strong Western influence (Manami, 2013). The large, round eyes that are considered cute are an import from the West (Kinsella, 1996). Kawaii as we know today is a result of the interaction between Japan and the United States after World War II.

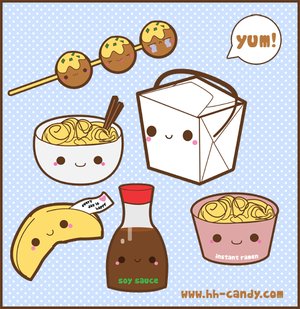

Kawaii is a compliment. Girls prefer to be called cute rather than sexy (Manami & Johnson, 2013). Kawaii has an element of inferiority and seeks to return to an idealized childhood (Kinsella, 1996). Products considered cute, such as Hello Kitty, are the result of Japan’s long focus on asymmetry and simplicity (Kato, 2002).

So what does kawaii mean? Childish, innocent, round, rebellious, loveable, pathetic, western, and acknowledged. Kawaii also means a person lacks negative traits (Kato, 2002). As I sketch kawaii’s history and role as an alternative to Japanese culture, I hope this word will clarify. We understand kawaii, cute, unconsciously. We know if something is cute at a glance. However, there is a lot going on behind and beside knowing something/someone is cute.

History of Kawaii

The first traces of cute can be found in the Edo period (1603-1868). Woodblock prints known a dijinga – literally “beautiful person picture” – depicted beautiful, cute people.

Kawaii took off with three major developments

- Girl’s Illustration

- Shojo

- Fancy Goods Marketing

Girl’s illustrations go back to the woodblock prints I mentioned. The first shoji and kawaii illustrator was Yumeji Takehisa in 1914. During this early period, kawaii referred to people of lower social standing. This did not change until the 1980s (Manami & Johnson, 2013).

Kawaii is said to be born with Takehisa’s work. His designs merged Eastern and Western art styles. He used round eyes in his illustrations. During the time, round eyes were considered vulgar. Takehisa was the first to use the word kawaii to refer to his chiyogami. Chiyogami is a flat woodblock print pattern on paper. The decorative paper was used for origami and other crafts (Ono, 2006; Manami & Johnson, 2013).

Kawaii and shojo – manga for girls – developed together after Takehisa. Katsuji Matsumoto, thought to be the founder of shojo, worked during the Showa era (1926-1989). The first shojo was Kurukuru Kurumi-chan. Kurumi-chan was also the first character icon. She showed up on paper dolls, stickers, and even post cards designed to encourage Japanese troops during World War II (Manami & Johnson, 2013).

As 1970 came and went, women increasingly illustrated and created manga for girls. The shift away from male authors changed what was considered cute. Much of the features and characteristics remained the same. However, female authors created cute characters that had an adventurous spirit and inner strength. Kawaii is the absence of negative traits (as in, what people during that time considered negative. What is considered negative changes slowly over time). Confidence and inner strength became positive traits in cute girls. Before the 1970s, most shojo readers were elementary school age. The expansion of the audience to teens and young women changed the definition of kawaii (Kinsella, 1996; Avella, 2004; Manami & Johnson, 2013).

As 1970 came and went, women increasingly illustrated and created manga for girls. The shift away from male authors changed what was considered cute. Much of the features and characteristics remained the same. However, female authors created cute characters that had an adventurous spirit and inner strength. Kawaii is the absence of negative traits (as in, what people during that time considered negative. What is considered negative changes slowly over time). Confidence and inner strength became positive traits in cute girls. Before the 1970s, most shojo readers were elementary school age. The expansion of the audience to teens and young women changed the definition of kawaii (Kinsella, 1996; Avella, 2004; Manami & Johnson, 2013).

Shojo also became a way of advertising and developing fashion. After World War II, fashion magazines did not target teens. The full body drawings of shojo characters in stylish clothing filled this gap (Manami & Johnson, 2013). Shojo culture, and by extension kawaii culture, encourages girls to identify with a group. This is done by wearing certain cute objects or clothing that belongs to a certain group. Think Goth Lolita or cell phone charms. Simply liking and wearing a character can make a girl a part of a larger group. What cute things a girl likes becomes a part of her identity. That identity is a part of a specific kawaii sub culture. This became especially true after 1974 with a design by Yuko Shimizu (Ono, 2006; Manami & Johnson, 2013).

Hello Kitty is one of the icons of kawaii culture. The company, Sanrio, has managed to keep Kitty White fresh by changing the design each year. These changes and the commodification of cute play into the efforts of teens to create their own identity. Hello Kitty does not cheapen kawaii culture. Takehisa, back at the birth of kawaii in 1914, opened a stationary shop that sold kawaii goods (fancy goods) to girls (Avella, 2004; Manami & Johnson, 2013). The commodification of cute was around since its birth. Hello Kitty spearheaded the modern trend of selling cute and is one of the most enduring symbols of kawaii culture.

Kawaii Handwriting

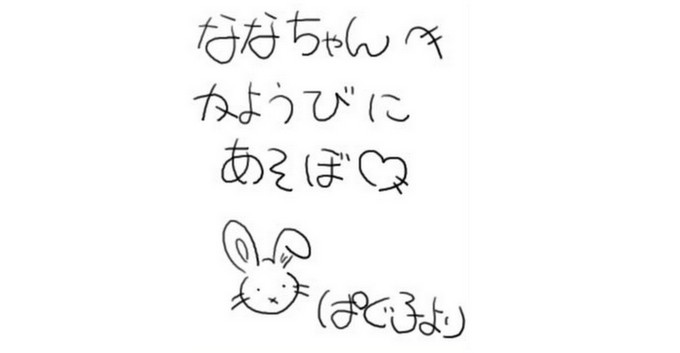

Cute handwriting is one aspect of kawaii culture that does not have roots in commercialism. Teens in 1974 began to write horizontally instead of the usual vertical manner. The letters were formed in a childish, rounded way instead of the more acceptable method. English and small drawings like hearts, stars, and faces became a part of the writing. The horizontal style was a yes to the West, which was seen as free and cool, and a no to tradition. Some schools banned this style of writing. The writing was called by many different names: marui ji (round writing), koneko ji (kitten writing), manga ji (comic writing), and burriko ji (fake-child writing). This invention allowed teens to speak freely in their own way for the first time and express their feelings more easily (Kinsella, 1996).

Cute handwriting is one aspect of kawaii culture that does not have roots in commercialism. Teens in 1974 began to write horizontally instead of the usual vertical manner. The letters were formed in a childish, rounded way instead of the more acceptable method. English and small drawings like hearts, stars, and faces became a part of the writing. The horizontal style was a yes to the West, which was seen as free and cool, and a no to tradition. Some schools banned this style of writing. The writing was called by many different names: marui ji (round writing), koneko ji (kitten writing), manga ji (comic writing), and burriko ji (fake-child writing). This invention allowed teens to speak freely in their own way for the first time and express their feelings more easily (Kinsella, 1996).

This was a huge development in teen identity. Japanese language was considered an art form and a lynch pin of culture – think calligraphy. For teens, both guys and girls, to create their own counter language, was an ultimate act of rebellion against traditional culture. The heavy American and European influence on the writing style also points to a shift in thinking about youth identity. Kawaii is centered on forming a sense of self and a relationship to a group of one’s choice. The sense of individual self is best seen in certain district of Tokyo: Harajuku.

Types of Kawaii

Cute is more then lace, frills, clumsiness, and childishness. Kawaii also has opposites that are considered kawaii.

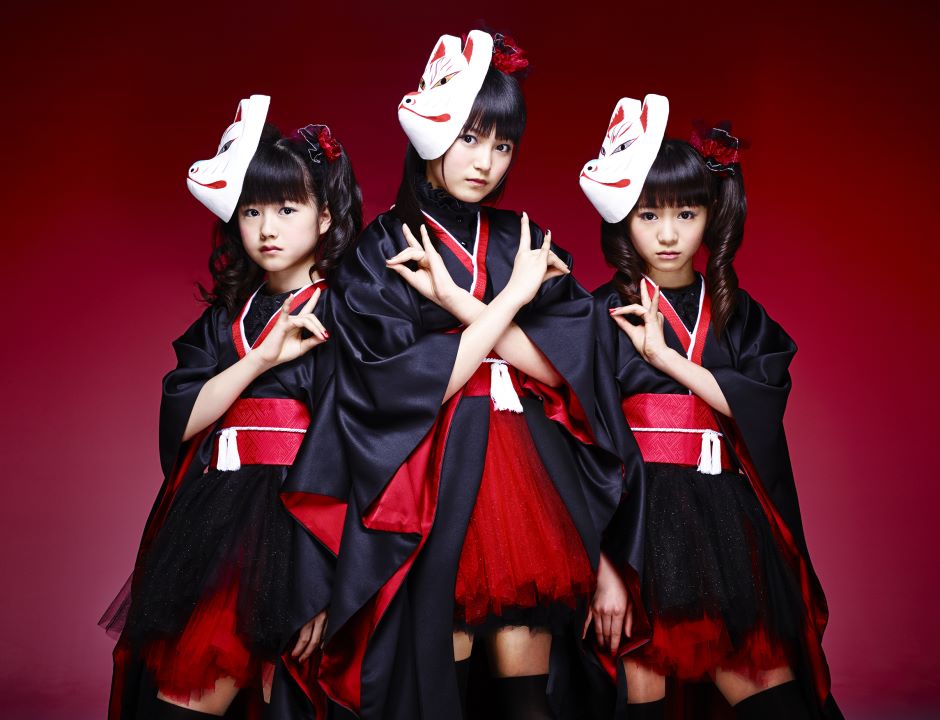

- guro-kawaii –grotesque cute. This is cute done in a disturbing, grotesque way. Think heavy, contrasted makeup.

- kimo-kawaii – creepy cute. Think cuteness to the point of being creepy.

- busu-kawaii – ugly cute. Can ugly be cute? This style plays up the feelings of pity associated with kawaii.

- ero-kawaii – sexy cute. Best example: the French Maid

- shibu-kawaii – subdued cute. Everyday cute. This is being kawaii without being overt. Wearing a single cute item and the like.

Street Kawaii

Harajuku was the center of all these different kinds of cute. The district was destroyed during the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. After the war, it was an American housing quarter called Washington Heights. This associated the district with the foreign, the different. In 1977, the district became a hokoten, pedestrian paradise. The absence of cars made the place a popular hang out for teens to see and be seen. Street fashion quickly developed. Harajuku became a blend of cosplay, street fashion and gothic fashion. Kawaii laced through all of it (Manami & Johnson, 2013).

Harajuku was the center of all these different kinds of cute. The district was destroyed during the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. After the war, it was an American housing quarter called Washington Heights. This associated the district with the foreign, the different. In 1977, the district became a hokoten, pedestrian paradise. The absence of cars made the place a popular hang out for teens to see and be seen. Street fashion quickly developed. Harajuku became a blend of cosplay, street fashion and gothic fashion. Kawaii laced through all of it (Manami & Johnson, 2013).

The year 1996 saw both a flowering and end of Harajuku. FRUiTS, a street fashion magazine, was the first to feature fashionable teens on Harajuku streets. Most fashion magazines were products of the industry. FRUiTS showed products of teens and young adults. In the same year, Harajuku was closed by police in a massive drug crack down. Harajuku was also a haven for drug sellers. Harajuku continued to exist on the streets, but the heyday was gone. Harajuku was also the center of cosplay from 1980-2000 (Manami & Johnson, 2013).

All the World is Kawaii

Kawaii is a culture and a sentiment. Kawaii is about contrast. Girls who try too hard to be cute are called fake. Things can’t be too cute. Perfection creates a sense of unease. Rather, cute is found in imperfection (Manami & Johnson. 2013). This is part of the appeal of kawaii. Girls, and boys, don’t have some impossible ideal of perfection to achieve (okay, kawaii does have some of this problem; it is just not a much as in American pop culture). Rather, a girl can be cute because she has that mole or a single drooping sock.

Kawaii is an international culture. Hello Kitty and other commercialized characters have spread far beyond Japan. Kawaii is a conversation between cultures. The west had an heavy influence on the development of kawaii, after all. Cute tends to be a cultural concept. The Cabbage Patch Kids, for example, were considered grotesque in Japan and cute in America. Yet, kawaii has a cross cultural appeal because it is rooted in universal images of children and baby animals. There are some images that make everyone feel protective or loving.

Kawaii is also an effort to relive an idealized childhood (Kinsella, 1996). Childhood was a time without worries or responsibilities. It was an idealized time of freedom. Kawaii allows a young woman in a stressful career to escape for a few moments to a few hours. Kawaii allows teens to find a shared identity through something as small as a cell phone charm.

Will kawaii lose its appeal?

No, kawaii will not completely lose its appeal. Its popularity will wane. It already has. Some companies move away from cute mascots. Banks, for one (Avella, 2004). Kawaii is grounded in an understanding of cuteness that comes from being human. Certainly, the Lolita outfits will eventually disappear, but girls and boys will continue to dress kawaii in different ways. Cute is an imperfect beauty that appeals to all of us. Because we are all imperfect, we all have the potential to be cute in our own ways.

Kawaii as a culture will last as long as people find cute, cute. The word may fall out of favor, but the ideas of kawaii will always remain.

References

Asiaone (2010). The doe-eyed world of Makoto Takahashi. http://news.asiaone.com/News/Latest+News/Showbiz/Story/A1Story20100611-221545.html.

Avella, N. (2004). Graphic Japan from woodblock and Zen to manga and kawaii. United Kingdom: Rotovision.

Kato, M. (2002). Cute culture. Eye. http://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/cute-culture.

Kinsella, S. (1996). Cuties in Japan. Women, Media, and Consumption in Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

Manami, O. & Johnson, G (2013). Kawaii! Japan’s culture of cute. New York: Prestel Publishing.

Ono, M. (2006) The simple art of Japanese papercrafts. Ohio: North Light Book’s.

Good article! Kawaii is an international culture. Hello Kitty and other commercialized characters have spread far beyond Japan. Kawaii is a conversation between cultures. The west had an heavy influence on the development of kawaii, after all. Cute tends to be a cultural concept. Best Regards

Thank you! Kawaii and anime can, perhaps, be considered among the first international media cultures. Hollywood tends to remain American despite spreading films across the world. Kawaii and anime culture can be considered an international dialogue.