Women are the emissaries of hell; they cut off forever the seed of buddhahood. On the outside they have the faces of bodhisattvas, but on the inside they have the hearts of demons.

–Buddhist Sutra

A woman’s talk does not go beyond one village.

A smart woman ruins the castle.

–Japanese Proverbs

Japanese medieval literature teemed with deceptive and dangerous women–devils in disguise with insatiable passions. Among these fantasies and frustrations caused by celibate life among literate monks were the Rasetsu. The Rasetsu were a race of shape-shifting cannibal women who seduced men and ate them alive. The women lived on Rasetsukoku. The island’s location changed throughout different periods, first appearing in Konjaku monogatari shu, a collection of stories about India in the 12th century (Moerman, 2009). “How Sokara and the Five Hundred Merchants Went to the Land of the Rasetsu” explains one of the first encounters with these women. It begins with a group of merchants setting sail in search of treasure.

They are shipwrecked on an island of beautiful women where each man takes a wife and enjoys a life of bliss. But Sokara, the sailor’s leader senses something is off and investigates. He finds a prison of men and signs of cannibalism. One of the prisoners tells him how he had enjoyed the same pleasures until a new ship washed ashore. Then, he and his mates were set aside for food. Sokara manages to get all but one of his crew to safety. However, 2 years later one of the women visits him at home, but Sokara wasn’t tricked. The King, however, falls for the beautiful she-demon and after spending three days with her in his bedchamber, she breaks out with a blood-stained mouth. All that was left of the king was “a pool of blood and hair.” In response, Sokara gathers an army and attacks the island. After destroying all of the demon-women he is made king of the island.

This land of demon women appears in a Ming Chinese encyclopedia of 1610:

The Land of Women is in the southeastern seas. The Water flows to the east. Lotus flowers one foot across bloom once a year and the peaches have stones two feet long. Long ago a ship drifted there and the women gathered together and carried the ship off. The sailors were all close to death. But a clever man among them stole the boat back at night and they were able to escape. The women conceive children by exposing their genitals to the sound wind. According to others, the women become pregnant by looking at their reflection in a well.

The Land of Women shifted from a fantasy sexual amusement park to a land of she-demons throughout different time periods, but it provides an early example of a cultural view of women that challenged feminist movements in the modern period. Women were relegated to a child rearing role and as household managers.

Women’s Rights and Legal Status

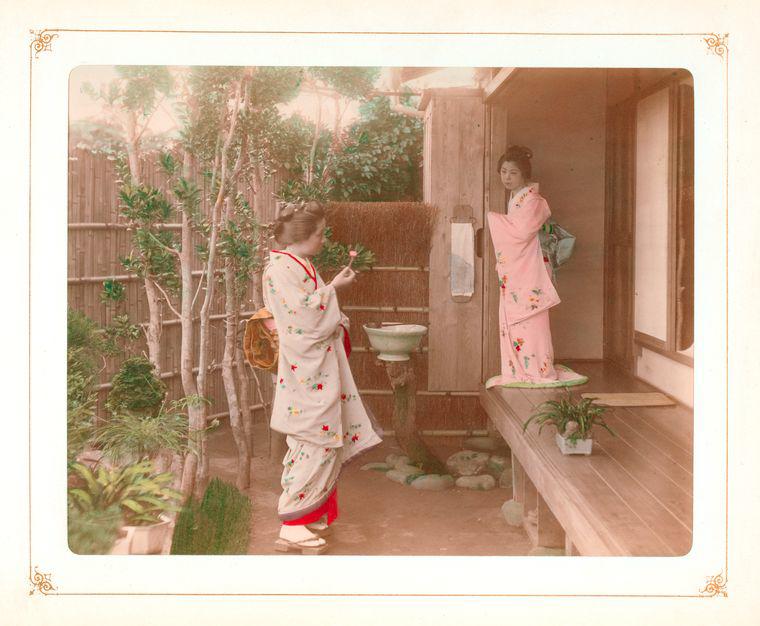

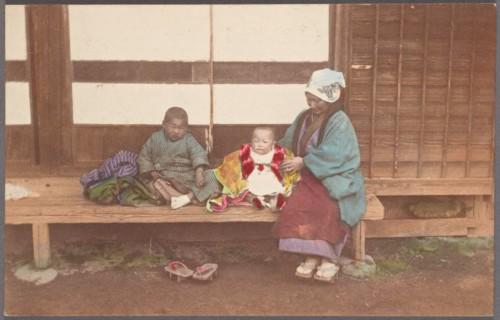

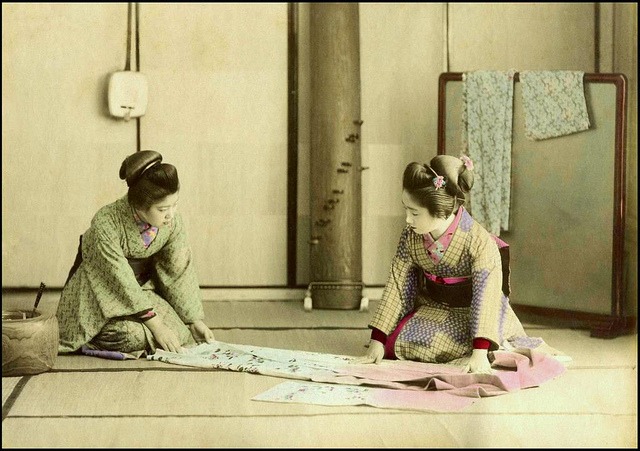

During the Tokugawa Shogunate (1602-1868), women did not legally exist. They could not own property and were subordinate to men. However, women in different classes had more rights than others.For example, samurai class women had fewer rights than the farming class, which needed women to help run the family far. The urban class allowed women to manage businesses. In fact, wives of merchants were expected to be literate. However, by today’s standards women lacked equality. A woman was still under the authority of men who decided the course of her life–who she married and more. Birth control didn’t exist as we know it. Midwives had their means, but women were expected to have children to continue the house.

During the Tokugawa Shogunate (1602-1868), women did not legally exist. They could not own property and were subordinate to men. However, women in different classes had more rights than others.For example, samurai class women had fewer rights than the farming class, which needed women to help run the family far. The urban class allowed women to manage businesses. In fact, wives of merchants were expected to be literate. However, by today’s standards women lacked equality. A woman was still under the authority of men who decided the course of her life–who she married and more. Birth control didn’t exist as we know it. Midwives had their means, but women were expected to have children to continue the house.

Equality became more of a concern during the Meiji Restoration, when Japan pushed to catch up with the Western nations in terms of military and technology and law. Japan looked toward Enlightenment ideals, exemplified by John Locke, when it examined its laws (Okin, 1998). These ideals later shaped the Universal Declaration of Human rights (1948), the Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights declaration, among others by the United Nations that proclaim equal rights of human beings regardless of sex. However, women remain discriminated against in differing ways. As Okin (1998) writes: “Indeed, discrimination on the grounds of sex is frequently justified as being in accordance with many of the cultures—including religions aspects of these cultures—practiced in the world today.”

However, both the 1948 declarations and Meiji Japan pulled from a 17th century system that was designed for male heads of households. Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers didn’t have women’s private rights in mind when they wrote their ideas of law and equality. For example, Locke states no one should interfere with a father’s decision to whom his daughter should marry:

In private domestic affairs, in the management of estates, in the conservation of bodily health, every man may consider what suits his own convenience and follow what course he likes best. No man complains of the ill-management of his neighbour’s affairs. No man is angry with another for an error committed in sowing his land or in marrying his daughter. Nobody corrects a spendthrift for consuming his substance in taverns.

This male bias sits deep in human rights thinking. Women have different life experiences than men that these old systems fail to take into account: rape—marital and war, domestic violence, reproductive freedom, valuation of childcare and domestic labor, unequal opportunity in education, unequal housing opportunities, unequal credit opportunities, and unequal healthcare. Okin (1998) points out how inequality can be obscured by cultural norms and what people consider natural, such as motherhood. Cultural norms against certain things, such as single motherhood, also obscure inequality.

This male-centric view of rights appeared in various Meiji Reformation laws. For example, in the Criminal Code of 1880, adultery applied to women only. Men couldn’t commit adultery on his wife, only with another man’s wife (Sasamoto-Collins, 2017):

Article 353: A wife guilty of adultery shall be punished by imprisonment of no less than six months and no more than two years. Her lover shall receive the same punishment.

The punishment shall be imposed only if the family formally lodges complaint. If he has tolerated adultery, his complaint has no effect.

Article 311: If a husband has discovered his wife’s adultery and killed or injured her or her lover immediately at the actual place where they were discovered, the crime is excusable.

However, this provision does not apply if the husband has tolerated the adultery.

In other words, women were punished for adultery solely based on her status as a wife. For the lawmakers at the time, this was a natural part of womanhood and Japanese culture, as Okin discussed. Men had to be certain their wives’ children truly carried their genes. Of course, prostitutes and other women didn’t fall under the law as their children didn’t factor into the family system.

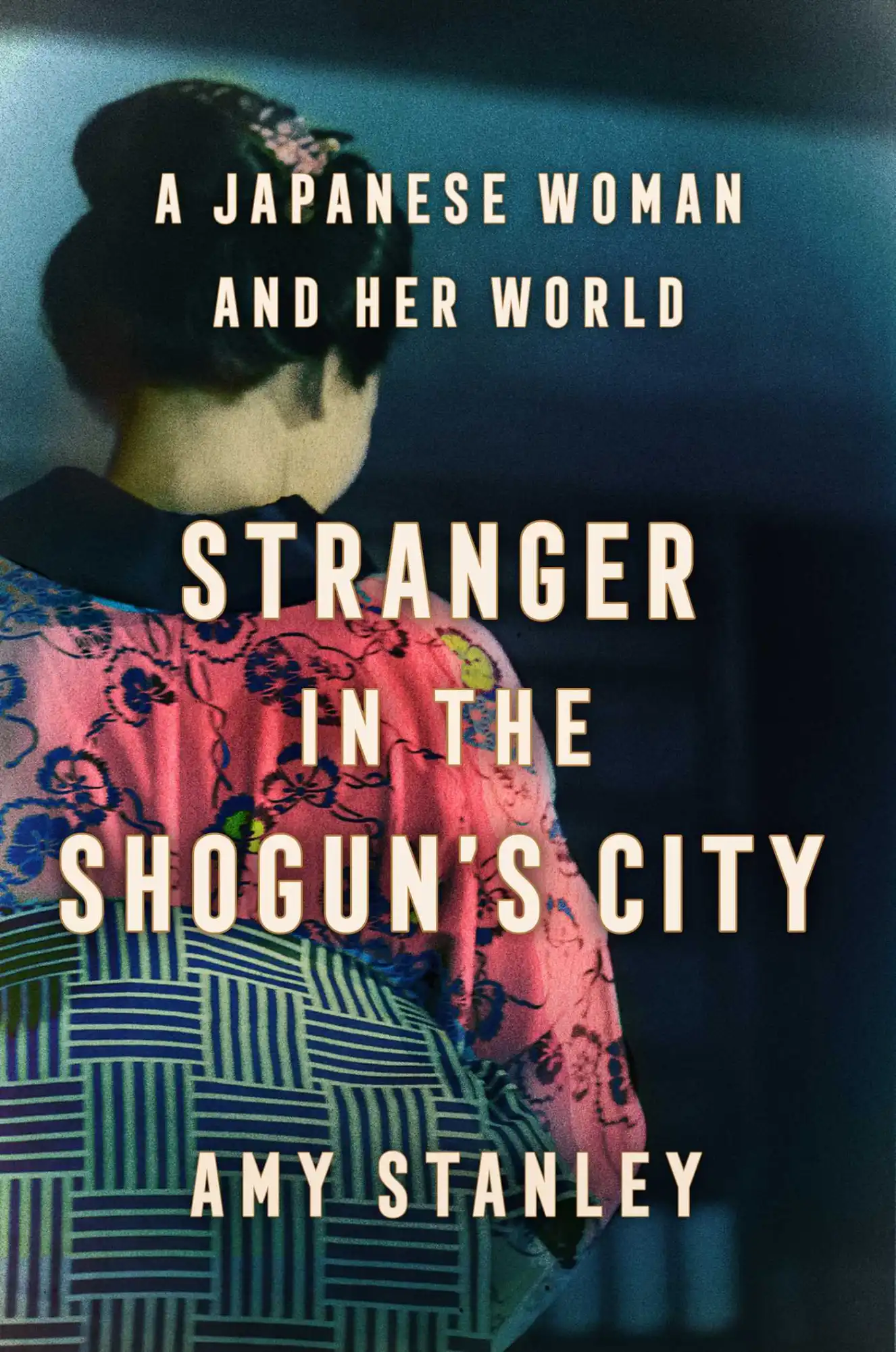

One Woman’s Observations of the Meiji Period

Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, born in 1878, wrote an autobiography that examined the differences between this type of environment and that of the United States. She married an American man and moved there to live with their daughters until he died. Afterward, she returned to Japan. The cross-cultural experience allowed her to write about both Japanese and American feminism at the time. She thought American women immodestly exposed their bodies “just for the purpose of having it seen” while Japanese women covered theirs from neck to ankle. When she returned to Japan with her two daughters she accounts (Kuo, 2015):

Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, born in 1878, wrote an autobiography that examined the differences between this type of environment and that of the United States. She married an American man and moved there to live with their daughters until he died. Afterward, she returned to Japan. The cross-cultural experience allowed her to write about both Japanese and American feminism at the time. She thought American women immodestly exposed their bodies “just for the purpose of having it seen” while Japanese women covered theirs from neck to ankle. When she returned to Japan with her two daughters she accounts (Kuo, 2015):

As I sat and thought, I wondered if Hanano was ever really happy anymore. She never seemed sorrowful, but she had changed. Her eyes were soft, not bright; her mouth drooped slightly and her bright, cheery way of speaking had slowed and softened. Gentle and graceful? Yes. But where was her quick readiness to spring up to my frst word? Where her joyous eagerness to see, to learn, to do? My little American girl, so full of vivid interest in life, was gone.

During Sugimoto’s life, the concept of ryosai kenbo, good wife and wise mother, was the focus of post Meiji Restoration (1868) education of girls. Before compulsory education passed in 1872, Confucian ideals prohibited women from getting an education. Girl’s education was seen as helping the nation as a whole, but it did little to break women from their traditional roles. In fact, education was seen as enhancing mothers’ abilities to produce patriotic, able citizens and supporting husbands. (Kuo, 2015). This education system, although a small step toward equality despite its failure to allow for different roles, contributed to the West’s misconceptions of women.

Sugimoto tried to correct this misconceptions–that Japanese women were less able to protect themselves and were less independent than American women. Japanese women were thought to be gentle and meek and needing American feminism to come in and liberate them. However, Sugimoto writes: “Although our women are pictured as gentle and meek, and although Japanese men will not contradict it, nevertheless it is true that, beneath all the gentle meekness, Japanese women are like—volcanoes.”

Sugimoto also illustrates how Japanese women had more rights than American women. Japanese women were the bankers of the family—responsible for both the family and for the family’s wealth. The husband must ask the wife for money, not the other way around like in the US at the time. She writes: “It was one of many exaggerated ideas that we had of the dominant spirit of American women and the submissive attitude of American men.”

American and Japanese Feminism Movements

In fact, during the early 1900s, American and Japanese feminism inspired each other. An early birth control advocate in Japan, Kato Shidzue, worked closely with American birth control activist Margaret Sanger. Shidzue brought Sanger to Japan in 1922 to speak on the topic (Kuo, 2015). The New Woman Association (NWA) in the early 1900s pushed for more rights, including a revision to the adultery law we examined which would allow women to file for a divorce if she discovered her husband or fiance had a venereal disease. The association framed their arguments in terms of protecting women’s family role–allow women to become better wives and wiser mothers through increased political awareness. They didn’t seek to completely break from ryosai kenbo. Most advocates focused on the improvement of women’s lives through better health, elimination of poverty, better work conditions, protection of motherhood, and similar goals instead of political ends. Political liberation was seen as a path to these ends (Molony, 2000).

In a 1920 article, Ichikawa Fusae, a leader of the NWA, wrote (Moloney, 2000):

Aren’t we treated completely as feeble-minded children? Why is it all right to know about science and literature and not all right to be familiar with politics and current events? Why is it acceptable to read and write but not speak and listen? A man, not matter what his occupation or educational background, has political rights, but a woman, no matter how qualified, does not have the same rights…If we do not understand the politics of the country we live in, we will not be able to understand conditions in our present society.

She pushed for absolute rights instead of women’s rights based on education or maternal roles–which laid the groundwork for later feminist activism after World War II. For better context, be sure to read my article about gender expectations of the Edo period.

Speaking of World War II, the good wife and wise mother role carried forward throughout and into today. Motherhood and housewife roles remain highly valued, but they leave little room for self-development and work-family balance. A survey of female seniors in 561 Japanese universities in 1992 found women expected and didn’t mind sexism at work. 91% said they don’t mind being treated as “office flowers” and 25% considered that to be a woman’s role (Thornton, 1992). This shows how strong the male-dominated view remained.

Modern Japanese Feminism

Today, young Japanese women postpone marriage. Intimate relationships with other women also increase in appeal—free from the motherhood association (Enns, 2011). The idea that a man should be dedicated to work and the good wife supporting him at home affects men in addition to women. Three-fifths of men between the ages of 25-35 remain unmarried. 53% of men in their 20s have never gone out with a woman. In contrast, 64% of American men claim to have had sex by the age of 20 (Homegrown, 2017). Women’s withdrawal from relationships to focus on career shows how they have moved beyond being “office flowers” in the 1990s. However, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), World Economic Forum, and the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Japanese women lag behind other developed countries in terms of labor participation and political representation. They have higher than average education rates, but many women don’t return to work after having children (Japan, 2016). Children remains an all-in affair for many Japanese women, which explains why so many are postponing or foregoing marriage and expectations of motherhood marriage brings.

Today, young Japanese women postpone marriage. Intimate relationships with other women also increase in appeal—free from the motherhood association (Enns, 2011). The idea that a man should be dedicated to work and the good wife supporting him at home affects men in addition to women. Three-fifths of men between the ages of 25-35 remain unmarried. 53% of men in their 20s have never gone out with a woman. In contrast, 64% of American men claim to have had sex by the age of 20 (Homegrown, 2017). Women’s withdrawal from relationships to focus on career shows how they have moved beyond being “office flowers” in the 1990s. However, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), World Economic Forum, and the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Japanese women lag behind other developed countries in terms of labor participation and political representation. They have higher than average education rates, but many women don’t return to work after having children (Japan, 2016). Children remains an all-in affair for many Japanese women, which explains why so many are postponing or foregoing marriage and expectations of motherhood marriage brings.

When asked why young men aren’t looking for a girlfriend, they answer that it’s too much trouble. Japan’s social segregation by gender doesn’t help matters. The combination of low self-esteem in men and fear of rejection by women opens the doors for teen idols, anime, sex dolls and sex pillow. Misogyny is a strange loop of love and hating because you love what you can’t have. And that idea of possession remains a problem too. The tension between feminism, traditional ideas of good wife and wise mother, and men’s views–which is a topic to itself–all add up to this trend.

Throughout all of this, the Japanese feminism movement worked. However, many of its leaders today are discouraged by how slow the progress over the past century has been despite the shift in marriage and the focus on career. Maternity harassment, sexual harassment, and employment discrimination remain real problems. Some progress is being made: there is greater acceptance of mothers returning to work and fathers taking on more child care responsibilities (Japan, 2016).

But the progress Japanese women have made toward equality remains tenuous. Misogyny and objectification of women remains rampant. Part of this is a result of culture. Japanese culture idealizes quiet, stoic endurance, which extends to sexual violence against women. They are expected to be Japanese and endure without complaint. Sexual harassment on commuter trains is an example. In the early 2000s, two-thirds of women surveyed reported being groped while riding crowded trains. In response, train companies introduced women only cars, but no other action was taken (Hayes, 2016).

Many Japanese women are victims of unwanted photographs, typically up-skirt photos on trains and other public places. Japanese cell phone manufacturers are even required to make cameras with audible shutter sounds meant to deter men from taking these photos of women in public places. All of this points to how a dominating, objectifying attitude toward women remains strong in Japanese culture. Despite efforts since the 1920s, oral birth control is still hard to get–doctors often prescribe low doses for one month at a time (Hayes, 2016). All of this extends from the traditional, deep-rooted view of women.

Many Japanese women are victims of unwanted photographs, typically up-skirt photos on trains and other public places. Japanese cell phone manufacturers are even required to make cameras with audible shutter sounds meant to deter men from taking these photos of women in public places. All of this points to how a dominating, objectifying attitude toward women remains strong in Japanese culture. Despite efforts since the 1920s, oral birth control is still hard to get–doctors often prescribe low doses for one month at a time (Hayes, 2016). All of this extends from the traditional, deep-rooted view of women.

Manga and anime carry on this view in many stories. Many sexually explicit, male-focused manga are violent toward women. They show women as sex toys and many of the stories of these comedies focus on the loss of male virginity while reinforcing men’s superior social status and women’s traditional status. This was a problem when Ito studied images of women back in 1994. From my own observations, this still remains an issue within anime and manga.

In fact, feminist scholar Chizuko Ueno looks at the pay gap between men and women (men are paid 26.6% more in a 2013 OECD study), media, and these attitudes and writes:

We struggled, fought, but unfortunately were incapable of making real change.

Gendertrolling

Japan isn’t alone in this problem, and the problem even extends onto the Internet in the form of gendertrolling. You are likely familiar with the word trolling, but I’ll go ahead and define it– “disrupting a conversation or entire community by posting incendiary statements or stupid questions for the person’s own amusement or because they have a quarrelsome personality.” The word first appeared in the 1990s, and most trolls on the English-speaking web are white, male, and somewhat privileged (Mantilla, 2013). Now, gendertrolling is a little different. . It involves numerous people who are often coordinated and the attacks persist online and offline—sometimes for years. Usually happens in response to women speaking out about some form of sexism. I’ll give you a few Western examples from Mantilla’s (2013) paper.

Japan isn’t alone in this problem, and the problem even extends onto the Internet in the form of gendertrolling. You are likely familiar with the word trolling, but I’ll go ahead and define it– “disrupting a conversation or entire community by posting incendiary statements or stupid questions for the person’s own amusement or because they have a quarrelsome personality.” The word first appeared in the 1990s, and most trolls on the English-speaking web are white, male, and somewhat privileged (Mantilla, 2013). Now, gendertrolling is a little different. . It involves numerous people who are often coordinated and the attacks persist online and offline—sometimes for years. Usually happens in response to women speaking out about some form of sexism. I’ll give you a few Western examples from Mantilla’s (2013) paper.

Melissa McEwan in 2007, who runs a feminist blog Shakesville, had her address and other information published online and received rape and death threats.

Anita Sarkeesian saw this when she started a Kickstarter to fund a project to point out sexist representation of women in the video game community. She received rape and death threats. The gendertrolls made pornographic images of her being raped, tried to have her social media accounts suspended, and tried to disable her website. They also released her personal information, including home address.

In 2012, Zerlina Maxwell, on the FOX News show Hannity, spoke about how the focus on ending rape should start with men instead of women carrying guns to defend themselves. The rape and death threats rolled in. Maxwell said, “Do not feed the trolls’ is really easy for people to say when you’re not getting 100 rape threats, when you’re not getting 100 death threats.”

Sexual harassment, including gendertrolling, tries to keep gender boundaries in place–preventing women from competing with men at work and preventing women from feeling safe in public places without a male companion. Japan’s problems with groping on subways and with inappropriate photos are good examples of this. Gendertrolling tries to keep these gender-boundaries in place online by attacking women who speak out online in male-dominated spaces, such as online video games. Not even Japanese women who serve in the Japanese government are safe from this problem. 52% report being targets of sexual harassment at least once (Osumi, 2015). The survey reports:

“Some respondents said they had been neglected or forced to buy cigarettes for their male coworkers, while others had endured taunts such as: “Why don’t you strip?” or “You must get excited by being groped.”

Some of these women work in Japanese legislators.

Feminism and misogyny are bound together. Misogyny results from women gaining some measure of equality and the perceived threat this can bring. Japanese women have come a long way from the Tokugawa Era and the Meiji Restoration, but many of the same problems back then continue today. Women in the United States still struggle with similar issues. Even when they are online, women have to face people who threaten them just for voicing an opinion or their experience.

Media adds to the pile. Manga and anime sometimes caters to sexist ideas, which only reinforces those ideas. Objectifying otherwise strong female characters through upskirt camera angles and other techniques that reduces them to sex objects encourages the thinking behind the problems women face. Yellow fever and orientalism, waifuism, and moe can all add to the headwinds.

Of course, feminism also has its own problem. Some activists look down upon women who want to be traditional wives and mothers. Women should have the freedom to choose this route if they want. In any case, with the issues of gendertrolling and continued pay inequality and continued objectification, Japanese women and women in general still do not have equal rights.

References

(2016) Japan Tries to Promote Women’s Rights, but Cultural Norms Stand in the Way. World Politics Review. http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/trend-lines/20172/japan-tries-to-promote-women-s-rights-but-cultural-norms-stand-in-the-way

(2017). Homegrown misogyny divides sexes in Japan. The Australian (National, Australia).

Enns, Carolyn (2011) On the rich tapestry of Japanese feminisms. Feminism and Psychology. 21 (4) 542-546.

Hayes, T. (2016). The Cultural Limits of Japanese Feminism. International Policy Digest, 3(6), 132-133

Hidari, Sachiko, McCormick, Ruth & Thompson, Bill (1979) Feminism in Japanese Cinema: An Interview with Sachiko Hidari. Cineaste 9 (3). 26-29.

Ito, K. (1994). Images of Women in Weekly Male Comic Magazines in Japan. Journal Of Popular Culture, 27(4), 81-95.

Kuo, Karen (2015) Japanese Women Are Like Volcanoes. Frontiers 36 (1) 58-89.

Mantilla, K. (2013). Gendertrolling: Misogyny Adapts to New Media. Feminist Studies, 39(2), 563.

Moerman, Max (2009). Demonology and Eroticism: Islands of Women in the Japanese Buddhist Imagination. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 36 (2). 351-380

Molony, Barbara (2000) Women’s Rights, Feminism, and Suffragism in Japan 1870-1925. Pacific Historical Review. 69 (4). 639-661.

Okin, Susan (1998) Feminism,. Women’s Human Rights, and Cultural Differences. Hypatia. 13 (2) 32-52.

Osumi, M. (2015, August 14). Over 50% of assemblywomen in Japan have been sexually harassed, survey suggests. Japan Times.

Sasamoto-Collins, H. (2017) The Emperor’s Sovereign Status and the Legal Construction of Gender in Early Meiji Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies 43 (2).

Sato, Kumiko (2004) How Information Technology Has (Not) Changed Feminism and Japanism: Cyberpunk in the Japanese Context. Comparative Literature Studies. 41 (3) 335-355.

Thornton, E. (1992). Japan: sexism OK with most coeds. Fortune, (4). 13.

Yamaguchi, T. (2014). “Gender Free” Feminism in Japan: A Story of Mainstreaming and Backlash. Feminist Studies, 40(3), 541-572.

I really appreciated your thoughtful exploration of Japanese feminism and gender roles. It made me reflect on how ideas of respect and balance can take very different shapes across cultures.

Many people describe wa (harmony) and amae (mutual trust and dependence) as quiet threads running through Japanese relationships. What may look like restraint from a Western perspective can sometimes reflect a wish to preserve connection and social balance.

There’s a certain elegance in how that sensitivity infuses daily life — perhaps part of what gives Japanese culture its grace and continuity. It may express equality through mutual responsibility rather than through self-assertion.

Thank you for opening such an engaging discussion. It’s inspiring to see how diverse cultures articulate the same human ideals in their own distinct voices.

Interestingly, the west has its own versions of wa and amae, appearing throughout the ancient world if in different ways. Medieval French Romantic literature has a type of these running through it, for instance. Japan’s relative isolation has led to some interestingly subtle expressions of universal human experiences.

Thank you for your thoughtful reply — I really enjoyed how you connected wa and amae with echoes in Western traditions. It’s fascinating how different cultures find their own ways to express harmony and mutual care.

Reading more of your posts, I’ve really appreciated your curiosity about Japanese society and art. It also made me curious about how English-language discussions often view Japan through gender or sexual critique. Those perspectives can be illuminating, of course, but they sometimes seem to overshadow the quieter aesthetic and philosophical layers that shape how Japanese people experience these same works.

In many areas of contemporary media — from idol culture, with its emphasis on presence, precision, and emotional sincerity, to anime and film — I sense a continuity of artistic ideals that reach back through traditional arts. What might appear “commercial” or “sexualized” from a Western lens can also be read as expressions of beauty, dedication, or the wish to harmonize individuality within a shared rhythm — not so unlike the sensibilities found in tea ceremony or Noh.

Your writing opens such meaningful spaces for reflection. I’d love to see you explore more of those aesthetic and cultural continuities in future pieces — they reveal how modern Japan often carries forward its deeper values in beautifully subtle ways.

It’s been over three years since this article, and our Japs’ sexism is still rampant.

Women are still thoughtlessly treated as sexual, the internet is rife with sexual advertisements, and books of girls in obscene poses are piled up in public bookstores.

The Japs don’t treat women as anything other than objects.

There is no way we can have a free climate and new innovations from such a country.

This country will be totaly defeated by its neighbors China and South Korea, and it will sink.

Unfortunately, many cultures struggle with this problem, not just Japan. The media and approach may be different, but the thinking behind objectification remains the same. I wouldn’t say all Japanese people treat women as objects. Sections of the media culture does. Beware generalizing too much.

* Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto married a Japanese man, not an American (was this information from Kuo?), and she came back to USA in the end, believing her daughters would be able to get a more rigorous higher education there than in Japan. As a widow living in NYC, she became the first female teacher at Columbia University.

* You should cite the source of the Ichikawa quote (with translator’s name), and mention her achievements in Diet elections; otherwise, we cannot appreciate the vantage point from which she was speaking. These and a few other quibbles distracted me, but it was interesting to read.

Yes the information came from Kuo.

I clarified the citation of the Ichikawa quote. Google already flags the article because of its length (at least the last time I looked) so I linked to another article about the Edo period to give people an idea of the historical momentum she and others faced.

Thanks for reading!