50% of one-parent Japanese families live below the poverty line (Ichino, 2014).

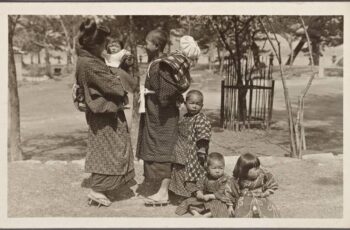

Japanese single mothers are one of those topics people do not talk about. Japanese society has a long history of divorce, but during the Meiji Restoration, divorce became a problem for women. The combination of strong family values and tax policies that support those values leave many single-mothers trapped. Japanese tax policy discriminates against women who choose to be single mothers. Divorced or widowed mothers have a few tax deduction options, however. However, most single mothers are single because of death or divorce. The Japanese government offers an allowance for single-mothers, but this fund has been in slow decline since it passed back in 1962 (WuDunn, 1996; Ono, 2010; Ichino. 2014).

Japanese single mothers are one of those topics people do not talk about. Japanese society has a long history of divorce, but during the Meiji Restoration, divorce became a problem for women. The combination of strong family values and tax policies that support those values leave many single-mothers trapped. Japanese tax policy discriminates against women who choose to be single mothers. Divorced or widowed mothers have a few tax deduction options, however. However, most single mothers are single because of death or divorce. The Japanese government offers an allowance for single-mothers, but this fund has been in slow decline since it passed back in 1962 (WuDunn, 1996; Ono, 2010; Ichino. 2014).

Single moms have it rough. Most of the articles I found focuses on the measurable data. Economic being the prime focus. These data doesn’t tell us what single-Japanese mothers experience. Only one study I found looked at how Japanese single-moms spend their time. The study discovered how single-mothers spend less time eating dinner with their children than married mothers, but both types of mothers spent the same amount of time with their children. This is impressive considering how single-moms have to work to feed their family (Raymo, Park, Iwasawa & Zhou, 2014). In other words, Japanese single-mothers are busy!

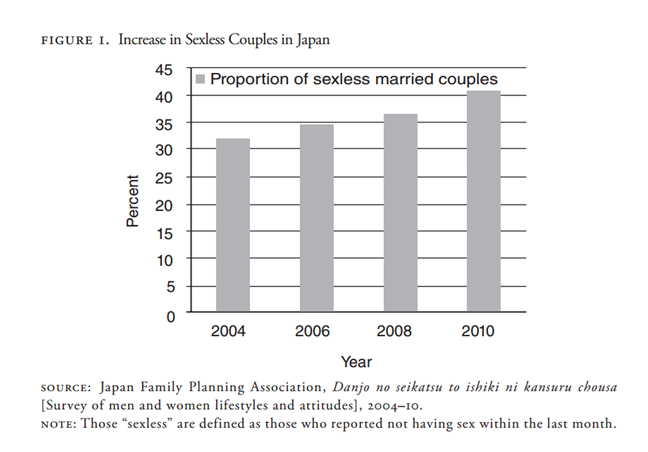

However, these moms also have other challenges, as if finding time to sleep wasn’t enough. In 2013, Shinzo Abe, the Japanese Prime Minister, admitted to a wide wage gap between men and women. Women earn an average of 30.2% less than men (Kiyota, 2015). She also faces challenges with even retaining her job. Only 38% of women keep their jobs after their first maternity leave (Kiyota, 2015). For many women, married or not, pregnancy ends any career aspirations. Is there any wonder Japan’s population is predicted to decline from 128 million in 2010 to 86.74 million by 2060 (Kyota, 2015)?

Now, I am not saying single Japanese moms do not work. Eighty to Eighty-five percent of single mothers work, but they earn an average of $20,000 a year (Itoi, 2005; Ono, 2010 citing Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare 2004). Single mothers face many economic problems. Time inflexibility is also a problem. In a Japan Times (2014) article, a single mother accounts how the expense of childcare facilities and limited school hours make it difficult to work. It can cost as much as ¥80,000 per child per month for some day cares (Ichino, 2014). That is about $800 a month.

What about child support? Don’t the dads pay for their children?

Child support doesn’t have much of a role in Japanese divorce. In about 70% of divorce cases, child support isn’t collected. Japanese culture has a practice called rien, the severing of all ties between ex-spouses upon divorce. Sometimes sorry money is paid, called isharyo (Ono, 2010). Unlike messy divorces here in the States, Japanese divorces are often final. There isn’t child visitation or child support payments. The finality of divorce is reflected in Japanese history as I will discuss.

As you can see, single mothers can have a rough time. Kakuchi (2002) tells of a mother who is sometimes forced to leave her child at home alone while she works late. Japanese workplaces are infamous for working males to death. It isn’t a surprise that women also face the same pressure. A single mother has to take on the traditional household responsibilities of both the wife and husband. Men do not face the same obligations toward children. As far as I can gather from my research, fathers have the freedom to walk away completely if they choose. This can be a detriment for the child. However, if the father is abusive, the finality of divorce can be a benefit as well.

Women that choose to be single mothers face discrimination on the job and with inflexibility of childcare facilities and schools. At least, so goes the thinking, widows and divorced women had their children within a marriage. These other women who didn’t marry break family tradition. This type of thinking is what encourages Japanese society to stigmatize single-mothers who never marry. Contrast this with attitudes in the US, where single-moms face some stigma, but nowhere near as much as in Japan. After all, child support in the US is enforced by law. Single mothers didn’t always have these problems or face these attitudes. Many of these issues and the shifts against single-motherhood came out of the Meiji Restoration.

The “Modernization” of Motherhood

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked the opening of Japan to the modern world. Tokugawa rule, which dominated much of medieval Japan, ended. With it ended many traditional Japanese practices, including divorce. Before Japan sprinted into the modern era, divorce had 3 practices. After Westernization, Japan only practiced 1 type of divorce. Traditional Japanese divorce was designed in a way that helped protect women’s well being. This is a little strange when you consider how male oriented Japanese society is. Anyway, single motherhood became more of a taboo after Japan modernized and sliced away two divorce protections for women. The three practices were (Ono & Sanders, 2009):

- Trial Marriage

- Returning to her family

- Divorce by mutual consent.

Only “divorce by mutual consent” remained after 1868.

Trial Marriage

Before the Meiji era, wives moved into the husband’s household on a trial basis. Many wives suffered from abuse and harassment, known as yome ibiri before this trial marriage practice became common. The trial period lasted about a year. The marriage could end with just a short written letter by the husband, called mikudari han. The wife didn’t suffer negative backlash like in formal divorce (where she would be blamed for the marriage’s failure). Both husband and wife remarried relatively easily because of the tentative nature of the marriage arrangement (Ono & Sanders, 2009).

Wife Returning to her Family

This practice made me think “well, duh, she would go back home to her family.” But, as we have seen from the data from modern Japan, and by what happens to some divorced women here in the States, women are not always accepted back to the family. The reasons can be social as well as economic. In pre-Meiji Japan, these divorced wives returned to the family’s farm. The family was expected to take her back, preventing the problems of displaced single mothers who cannot properly support themselves. Called demodori – a person who left then came back – these women did not suffer from stigma because the marriage didn’t work out (Ono & Sanders, 2009).

You will notice that the chastity of the woman isn’t even a factor in this and other arrangements. Female chastity didn’t hold as high of value in traditional Japan as in the West. Of course, the wife could not commit adultery, but her virginity wasn’t as much of a factor as in Western marriages.

Divorce by Mutual Consent

This is the practice Japan kept after modernizing. This practice made certain the wife had a say in the decision to divorce. The husband could not dissolve the marriage on a whim. Before this practice, husbands could dissolve the marriage whenever they wanted. Sometimes, unhappy wives pressured their husbands to writing his divorce letter (Ono & Sanders, 2009). This practice also protected the wife from the idea that something was wrong with her. When husbands could essentially throw a wife out, people would wonder what she did wrong or what she had wrong with her to make him do so.

The End of the Tradition and the Rise of Stigma

Ending two of the three practices removed the protections women had. This opened the door for the discrimination of single mothers. The end of the trial marriage system placed the blame on women for failed marriages. In Japan, women are expected to manage the household. Divorce shows she is unable to do her role in society (Ono & Sanders, 2009). Basically, divorce after the Meiji era labeled the woman as a social failure. This idea extends to single mothers who did not marry before having children. She failed to fill her societal role as a household manager.

Ending two of the three practices removed the protections women had. This opened the door for the discrimination of single mothers. The end of the trial marriage system placed the blame on women for failed marriages. In Japan, women are expected to manage the household. Divorce shows she is unable to do her role in society (Ono & Sanders, 2009). Basically, divorce after the Meiji era labeled the woman as a social failure. This idea extends to single mothers who did not marry before having children. She failed to fill her societal role as a household manager.

The increase in stigma eroded the ability of divorced women to return to their families. This led to the difficult situations divorced single mothers face today. The stigma also influences tax policy that discriminates against single mothers. The shift away from family farms toward modern business practice further eroded the ability of families to re-absorb their daughters and her children.

It is an understatement to say single Japanese mothers have it difficult. Their government stipends are constantly being cut, and Japanese business shows little signs of accommodating single mothers from what information I have found. The United States is more accepting of single motherhood than Japan. While the US stigmatizes single mothers, it is not as extreme as in Japan. In this regard, Japan could learn from the United States.

Edit: 2/19/2016

As a kind reader pointed out, some sections of this article appear to be misleading. First, Japan has expanded its support for single mothers and fathers in 2015. Next, the stigma isn’t as problematic as my text may make it appear. Single mothers have made strides forward and away from the stigma of the Meiji period. It also points to how the Meiji period was a deviation from the past where women had some rights. Apparently, my writing didn’t make this as clear as I intended. Finally, most Japanese women are single through divorce and death instead of by choice. The references I use also support this.

References

WuDunn, S. (1996) Stigma Curtails Single Motherhood in Japan. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/13/world/stigma-curtails-single-motherhood-in-japan.html

Ichino, R. (2014). Japan’s persisting gender gap leaves many single moms in poverty. Japan Times. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/12/10/national/social-issues/japans-persisting-gender-gap-leaves-many-single-moms-in-poverty/#.VVapGJP_-PU

Kakuchi, S. (2002). In Japan, Moms defy tradition by staying single. We-news.

Itoi, K. (2005). Struggling To Get By. Newsweek (Pacific Edition), 145(19), 51.

Ono, H. (2010). The socioeconomic status of women and children in Japan: comparisons with the USA. International Journal of Law, Policy, and the Family. 24 (2) 151-176

Kiyota, T, et al (2015). Womenomics: solution for Japan’s decline? PacNet 8: Pacific Forum CSIS.

Raymo, J., Park, H., Iwasawa, M., & Zhou, Y. (2014). Single motherhood, living arrangements, and time with children in Japan. Journal of Marriage and Family 76. 843-861.

Ono, H. & Sanders, J. (2009). Divorce in contemporary Japan and its gendered patterns. International Journal of Sociology of the Family. 35 (2) 169-188.

I was told by a Japanese female that after her mid-30s, if she remained unmarried, she would receive a disability benefit. Therefore she was desperate to get married. I can’t find any evidence to support this, have you any idea what I may have misheard?

I asked a Japanese friend. She told me remaining unmarried doesn’t qualify for a disability benefit, but welfare is available for those at lower income (which single women often would be).

This article is extremely bias. For those fathers who do want to take part of the child’s life and the mother chooses not to – that’s on her.

Perhaps the narcissistic characteristics of most Japanese women is the reason for men not partaking ?

Many fathers are shut out of their children’s lives because of their mothers. However, I wanted to focus the article on the struggles many single mothers face. Single fathers face a different set of struggles. Struggles which need more academic research. Academic research has focused effort on researching women’s problems at the expense of examining men’s issues. My article suffers from this problem. But in academia’s defense, they ignored women’s problems for some time and are now making amends.

Not all single mothers are “victims of social injustice”…

Many of these single mothers today are in fact child-abducting criminals.

Why not mention child abduction issues in Japan and how fathers are denied the right to spend quality time with their children?

Research the issue thoroughly, not just through the eyes of feminists.

Regards

Patrick Davis

You are correct, not all single mothers are victims of injustice. I apologize if I lend that impression.

As for fathers, we’ve touched on issues with how they can’t spend time with their children before in “ Worked to Death – Karoshi and Japan’s Deadly Work Culture,” “Gender Roles of Men in Japan.,” and anime’s negative view of men in “Anime’s View of Men.” As for child abduction, I’ve considered writing about that topic at some point.

This article was written in 2015 but some of your key sources are more than 15 years out of date.

The business about stigma is exaggerated and irrelevant. Most single mothers in Japan are in that situation because of divorce or death of their husband, not because of out of wedlock birth.

If anything, aid to single mothers has expanded over time. Aid to single fathers has also been expanded.

This blog item describes the many forms of aid and discounts that were available as of early 2015.

http://single-mama.hatenablog.com/entry/2015/01/14/130308

Thanks for the link and the comment!

I used older sources to point out the history of single motherhood in Japan. I let the dates stand to show some continuation between the decades. You will notice how these sections use 2014 and other, older citations. I perhaps should have made this clearer. The fact most single mothers are single because of death or divorce is a contrast to the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control, “About 4 in 10 U.S. births were to unmarried women in each year from 2007 through 2013.” The rate is on the decline, but from what I gather it is still a much higher ratio than in Japan.