When we think of monks, we think of bald guys sitting around praying and studying all day long. Monks shirk women, booze, and other worldly pleasures. Back in the 15th century, one Zen monk turned this tradition on its back. Ikkyu Sojun decided to be true to himself and that meant regular trips to brothels. Ikkyu decided to challenge the established practices of Zen by doing the opposite.

When we think of monks, we think of bald guys sitting around praying and studying all day long. Monks shirk women, booze, and other worldly pleasures. Back in the 15th century, one Zen monk turned this tradition on its back. Ikkyu Sojun decided to be true to himself and that meant regular trips to brothels. Ikkyu decided to challenge the established practices of Zen by doing the opposite.

Ikkyu was born into the imperial household in1394 as the unrecognized child of the Emperor Gokomatsu. For reasons we don’t know, his mother fled the court before Ikkyu was born. We know little about her. In her only surviving letter, written shortly before her death, she urged Ikkyu to become such an outstanding priest that he might consider Shaka and Daruma, fathers of Zen Buddhism, his servants (Keene, 1966; Qui, 2001). In a postscript, she added a line that reveals a hint of her personality:

The man who is concerned only with expedients is no better than a dung-fly. Even if you know by heart the 80,000 holy teachings,unless you open to the full the eyes of your Buddhist nature, you will never be able to understand even what I have written in this letter.

His mother sent him to Ankokuji in Kyoto as an acolyte at the age of 5. For the next 10 years, he trained in Buddhist scriptures and Chinese classics. Ikkyu developed a reputation as a master of Chinese poetry, some of his earliest surviving poems dates to when he was between 12 and 14 years old. In his teens, he grew tired of the status seeking of the temple and left to become a disciple of Ken’o Soi, an eccentric Zen master who refused to accept his seal of transmission, a document that certified his enlightenment and status as a Zen master. Ikkyu stayed with Ken’o until Ken’o’s death in 1414.

After this, Ikkyu joined another hermitage under the harsh master Kaso. Kaso appears to have soured Ikkyu to the Zen establishment. In 1420, Ikkyu had an enlightenment experience at the age of 26. During a late summer night, as the rain clouds hung low over a lake, Ikkyu sat in meditation in a small boat when he heard crows call. He suddenly cried out as realization struck him. After this experience, he became a Zen master in his own right; however, when Kaso presented the seal of transmission, Ikkyu refused it like his previous master did. This began his crazy career as a brothel regular and protester of established Zen.

Ikkyu believed in the Zen idea of the unity of opposites, the idea that light and dark were one. Despite his antics, Ikkyu took Zen seriously and attacked anyone he deemed lacking in sincere Zen spirit. In his poems, he loved to contrast the practice of Zen with explicit descriptions of sex. During his lifetime, Ikkyu saw the superficial Heian period end and the beginning of the Kamakura period. The Heian period’s flashiness rubbed off on the Zen establishment, troubling Ikkyu. One day, Ikkyu lost a favorite ink stick and became so upset he became sick. He used this to point out the superficial focus of his age (Qiu, 2001):

Aah, in today’s world, people are all crazy about treasures and wealth; to them an ink stick would be no more than a broken straw sandal. But I almost lost my life over a missing ink stick. I wonder if those who have many desires would feel a little shame when they heard this poem.

The transition between the Heian period to the Kamakura marked a time of violence. Ikkyu lived through wars between samurai families, peasant rebellions, and the destruction of Kyoto, the city of the Emperor. This time of upheaval explains why he tried to use pleasure and poetry to get through to people. Most of his poetry sliced at established Zen for allowing corruption to shape their purpose:

From the world of passions,

I return to the world beyond passions,

A moment of pause.

If the rain is to fall, let it fall;

If the wind is to blow, let it blow.

Ikkyu favored brothels over temples as places to meditate. It’s likely brothels provided a more receptive audience than monasteries for his teachings. Ikkyu taught sexual desire was a natural need, like the need for water. Denying sexual desire broke the purpose of Zen, which is to help a person discover their true nature. Sexual desire, according to Ikkyu, was a part of a person’s nature. In the poem titled “Fisherman” he denounces the values of Zen communities:

Learning the Way and studying Zen, one loses the Original Mind.

A fisherman’s song is worth a thousand pieces of gold.

Evening rain on Xiang River, the moon amid the clouds of Chu—

It’s boundless furyu to chant poems night after night.

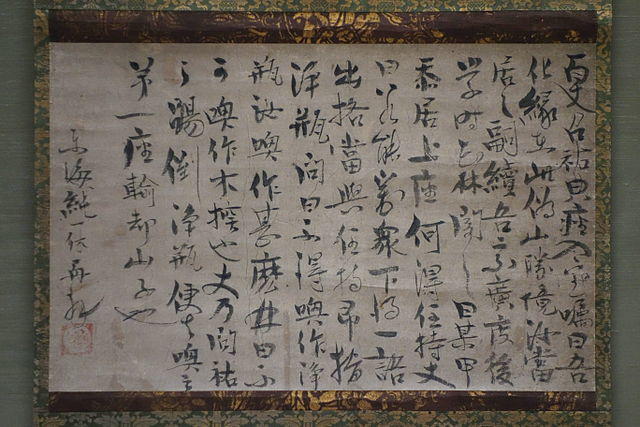

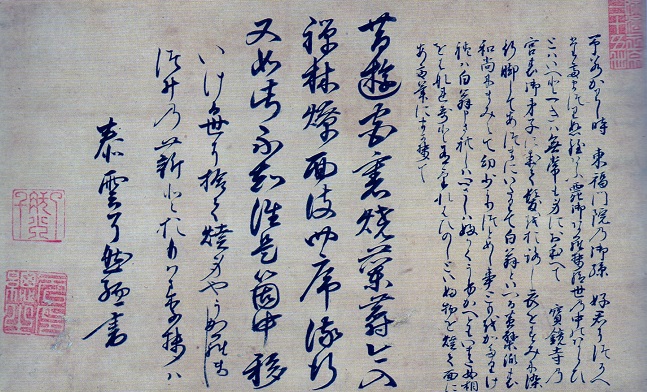

Ikkyu not only ignored the practice of celibacy, but he also ignored grooming practices, sporting hair and a beard instead of the bald, clean shaven practices require of monks. A portrait drawn by his disciple Bokusai shows his unseemly appearance–to the eyes of other Zen priests Ikkyu looked unseemly (Keene, 1966). On New Year’s Day, Ikkyu would parade through the streets with a staff topped with a human skill to drive home the impermanence of life. Shock served Ikkyu well.

Ikkyu’s Furyu

Furyu is a hard concept to define, and it stands at the heart of Ikkyu’s erratic behavior as a priest. The concept changed across the various periods of Japan. During the Heian period, furyu referred to the sensuous beauty of artificial objects and art. During the Edo period, long after Ikkyu’s death, the word came to focus on eroticism. Sex and sensuality remained attached to the word. Ikkyu’s furyu is best considered “an aesthetic of unconventionality celebrates the freest mind, which, to the orthodox point of view, is crazy and eccentric (Qiu, 2001).” This idea explains why Ikkyu frequented brothels. His antics tried to shake up the thinking of the time, breaking everything thought to define Zen Buddhism. Ikkyu’s furyu retained its attachment with sexuality when he used the word in his poetry:

Furyu of the age, a fair lady;

Love songs, delicate feast, melodies exceptionally novel.

Singing a new song, I lot my heart to her lovely face and dimples,

As the flowering haitang [Chinese crabapple tree] of the Tianbao time, Mori, you are a sapling in the spring.

“Seeing My Beautiful Mori Taking a Nap,” uses furyu to equate Mori’s beauty as the peak of sensuousness. The Chinese crabapple tree was a symbol for beautiful women in Chinese poetry. Ikkyu used the word in both the expected way of the period and in his own way, adding to the complicated understanding of the word.

Ikkyu’s poetry reveals this complication through contrast. One moment he expresses doubt toward the value of the pleasure district:

Ten years in the gay quarters, and still I couldn’t exhaust the pleasures;

But I broke away and am living here in empty mountains and dark valleys.

In these favorable surroundings clouds blot out the world.

Then he turns around and writes as if he had no doubts about his way of life being compatible with Zen:

To sleep with a beautiful woman?

what a deep river of love!

Upstairs in a tall building the old Zen priest is singing.

I’ve had all the pleasure of embraces and kisses

With never a thought of sacrificing myself for others.

Ikkyu’s life acts as a koan. Despite his dislike for establishment, he became an abbot in 1474 of Daitokuji and managed to ease the conflicts between Daitokuji and Myoshinji schools of Zen. But his feelings about being an abbot remained mixed as his bitter poems from this period shows. He leaves the position shortly after taking it and returned to his previous lifestyle. In his final years, Ikkyu wrote erotic poems about a blind singer named Mori. He died in 1481 at 87 years old.

Ikkyu’s Legacy

Ikkyu lived a life of contrasts. He knew the austere life of a traditional monk at an early age, and he knew the life of indulgent pleasures to be had at brothel and bar. Even for his time, his eccentricities were hard to understand. He spent his life slicing at establishment, showing how the extreme withdrawal from sexual desires was the same as indulging in them. He advocated for a balanced view by showing sexual desire was no different than thirsting for water.He denounced how the great Zen temples focused on increasing their wealth and power.

Ikkyu lived a life of contrasts. He knew the austere life of a traditional monk at an early age, and he knew the life of indulgent pleasures to be had at brothel and bar. Even for his time, his eccentricities were hard to understand. He spent his life slicing at establishment, showing how the extreme withdrawal from sexual desires was the same as indulging in them. He advocated for a balanced view by showing sexual desire was no different than thirsting for water.He denounced how the great Zen temples focused on increasing their wealth and power.

His messages strangely resonate with modern Christians. Christianity today focuses upon traditional purity and appearance while wealth and power corrupts churches. Ikkyu, in his crazy way, points out how religion labels everything in a ritualistic way, creating artificial divisions. These artificial divisions get in the way of understanding reality.

Ikkyu’s poems and prose capture a time of change and a complicated, eccentric figure in Japanese history.

I’ve left in the temple the things I’ve always used,

My wooden spoon and bamboo plate, hung up east of the wall.

I don’t want your useless furniture around me;

For years a peasant’s hat and cloak have been enough.

References

Keene, Donald (1966) The Portrait of Ikkyu. Archives of Asian Art. 20. 54-65.

Qiu, Peipei (2001) Aesthetic of Unconventionality: Furyu in Ikkyu’s Poety. Japanese Language and Literature. 35 (2). 135-156.

Sojun, Ikkyu and James Sanford (1980) Mandalas of the Heart. Two Prose Works by Ikkyo Sojun. Monumenta Nipponica. 35 (3). 273-298.

Yes, and yes. But have you read The Carnal Prayer Mat? Not even the most accomplished Zen masters can escape their personal karmas; and even the dharma-eye has its blindspots. Interdependence works across time and space and the only outcome of fighting conditions is weariness. Ikkyu’s mother told him well how it really is.

What is the name of the space between the brothel and the cloud hall?

I haven’t read that work yet. It makes sense not even Zen masters can escape karma, nor would they want to! They wouldn’t be Zen masters anyway.

As for your question: there isn’t a space between the two ; ).

space cadet asks about space, as a fizh might ask about water.

Ikyyu is the only truthful man that ever lived.

That’s a bit of a hyperbolic statement. He did offer an interesting perspective.