Most of us here in the US have probably come across people we would classify as “hermits”. That is to say, they barely leave the house, tend to be introverted, have few friends, and generally pass through life trying to be noticed as little as possible (weirdly enough, this might give them a kind of notoriety, like the “crazy old witch lady” that television tells us lives in every small town).

Now, there is nothing wrong with liking your solitude. However, as with anything, it can be taken to an unhealthy extreme. The Japanese word for such people is “hikikomori” which can translate literally as “pulling inward, being confined”, and it refers both to individual people and the phenomenon in general. While definitions vary, to be considered hikikomori, a person must have completely withdrawn from society for six months or more (three months in Korea, which goes to show that a hard and fast definition has proven elusive). It occurs in the absence of any other psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or agoraphobia. Disorders might develop later, but it is often unclear whether they developed prior to or because of hikikomori

Hikikomori completely withdraw from society, giving up work, school, friendships, and all other social ties. They go into a self imposed exile, locking themselves in their bedrooms for the better part of the day. Not all are completely housebound; some will venture out to buy food from 24-hour convenience stores, doing so at night when they are unlikely to run into other people, while others occasionally mount expeditions to obtain CDs and DVDs (although with the advent of piracy, Spotify, and Netflix these small forays into the wider world are probably greatly reduced for many). Mostly, they spend their days on the internet, playing video games, or watching television. Some do nothing at all, passing the hours lost in their own head.

The vast bulk of those afflicted (80% by some estimates) are males. Numbers vary, but hokikomori may afflict up to 1% of Japan’s population, putting the number of sufferers at 1 million people. More conservative estimates put the number at between 200,000 and 700, 000. The age of onset for the disorder is variable, but it usually strikes in those under the age of 30. It might be brought on by some sort of social or educational failure, a traumatic event of some sort that causes the hikikomori to withdraw to hide in shame. It could be bullying, or failing an university entrance exam, or perhaps failure to secure a good paying job after university. One early symptom of hikikomori is futoko, or school refusals. The hikikomori may also become unhappy, lose friends, become depressed, and start to become less talkative before they begin their exile.

As crazy as it sounds, this behavior can go on for years. There are some hikikomori who are now in their 40’s, the so called “First Generation”, who have been in exile for twenty or more years. This has lead to what has been called the “2030 problem”; basically, when these people’s parents, who are in their 60’s now, start to die in the next twenty years, what is society going to do with an influx of people who haven’t left their house in forty years, who haven’t interacted with anyone, formed any real relationships, nor moved about the modern world in all that time?

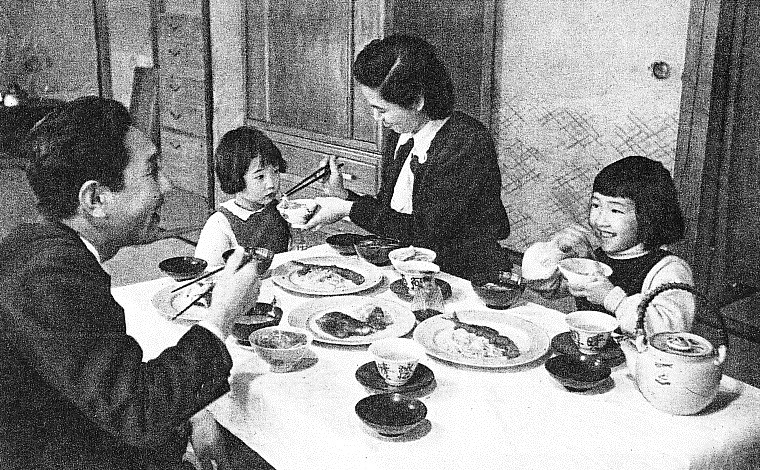

That’s right — these people are in their 40s and dependent on their parents. The majority of hikikomori are completely dependent on their parents for their survival during their self-imposed exile. Such a thing might be baffling to Westerners, where it is considered normal for a child to leave home at 18 to strike out on their own (although such a thing is less common now than it used to be, it is still a force in the culture). The typical American response when confronted with the phenomena of parents supporting their children well into their 40s (I’ll freely confess it was mine as well): “Why don’t they just kick them out?”

We’d call it “tough love”. And it happens a lot; that’s considered a normal part of parenting in the West, to a greater or lesser degree. But the Japanese response to that would be to blink in confusion and say “Why? Don’t you love your children anymore?”

And here, for many researchers anyway, is the heart of the matter. You may have noticed by now that Japanese culture is different than ours here in the West. It is Japanese culture itself, in the opinion of many folks who research hikikomori, is responsible for the epidemic of shut-ins.

Economics and Culture: the Origins of Hikikomori

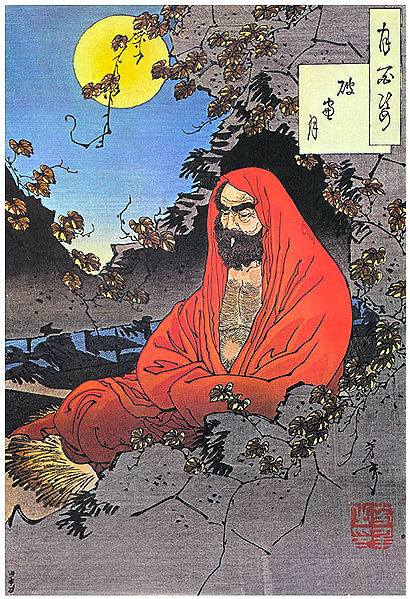

Asian countries in general and Japan in particular have a long history of extolling the virtues of solitude. Religious figures such as Buddha, Bodhidharma, and other heroes and prophets of Eastern traditions spent significant amounts of time alone, contemplating the nature of the universe (Bodhidharma, a figure in Chinese Buddhism, once reportedly spent seven years staring at a cave wall, by way of example). The Japanese Zen tradition, and Shinto before it, also celebrated the nobility of solitude, and there are many poems and literary works that illustrate this cultural habit.

You can see the emphasis on solitude in the history of Japan itself, who only opened itself to the rest of the world in the 19th century, and then only under the threat of American naval guns. It seems that being set apart, alone, is part of the Japanese psyche in a very fundamental way, and that tendency manifests in the withdraw of the hikikomori from the modern world.

That is admittedly esoteric, and perhaps a little romantic; I don’t mean to romanticize this disorder at all, which has crippling consequences for both families and individuals, and might in the future cause huge difficulties for a country that already has its fair share of demographic and economic woes. The point is that these cultural tendencies might well contribute to the phenomena.

Attitudes toward academics and success probably have more a more immediate impact though. If America’s “high stakes” testing is ridiculous, then Japan’s is downright torturous. Advancement to each level in the Japanese education system is determined by tests. How a student scores on said tests determines which educational track they fall into. Ideally, a student would pursue the track that would propel them toward an elite university, such as the University of Tokyo. The most important test of all comes after high school; the university entrance exams, the mother of all tests. Aspiring university students get one shot, that’s it. Literally their whole future hinges on that ONE test.

Then, if they pass that monster of a test (many students will take time off to study between one and three years for entrance exams, to give you an idea of how bad it is), students get the distinct sadomasochistic pleasure of working through an elite university. And then, if a person has the misfortune of having graduated in the last five years since the global economy tanked, they graduate into the worst job market in modern history.

In Japan it used to be that you graduated and took a job with a multinational corporation, where you would work the rest of your life. Employment for the fathers of many hokikomori was secure; indeed, the careers they started in their youth are what support their sons in exile. Their sons, however, are graduate now into an unsteady job market, where the old “salaryman” jobs are fewer and farther between, and many college graduates (like their American counterparts) wind up taking jobs that they are vastly overqualified for.

The difference is that in America, there is room to move up. In Japan, it’s highly unlikely. Failure to secure a good corporate job after university puts a stigma on a person they aren’t likely to shake off. To say that the academic/economic environment of Japan is competitive is like saying that rugby is a rough game or the Second World War was a minor scuffle. You win or you lose. Their isn’t an in-between.

To many who come out of that system, only to open the final door of achievement and find nothing behind it, is there any wonder that they withdraw? The pressure to succeed, and not to just succeed but to excel, is too much for some. It leaves them feeling ashamed, like they are utter and complete failures. And it might happen early; some of the youngest hikikomori are 13 or 14 when they first lock their bedroom doors.

That might be the heart of the issue: shame. Many Asian cultures are big on the notion of saving face. In Japan, conformity is demanded; “the nail that sticks up is hammered down,” as the saying goes. The hammer is shame. In the case of hikikomori, they hide the vast shame they feel at their failures, real or perceived, by literally hiding themselves from the larger society.

Hikikomori: the Family Dynamic

However the broader economic and cultural strains might contribute to hikikomori, the maintenance of the disorder for months, years, and even decades comes down squarely to the family dynamic. Japan has always pressured its youth to succeed, and it comes down to parents to be the enforcers of that cultural imperative. It might seem strange then that parents who are, in the Western mind, exceedingly strict would allow their children to lock themselves in their rooms for decades at a time without saying much of anything about it.

It is difficult to pin down the exact causes to some extent, because of course each family has its own dynamics, but generally speaking Japanese parents of hikikomori take a soft approach at the onset of symptoms, thinking that it is just a phase, that their son (or in some cases daughter) will grow out of it and return to normal soon enough. But as the months pass with no change, a sense of shame sets in. Many parents take it that they have failed in parenting, that if they had done something different with junior, he might have turned out differently. Fear also sets in, a fear of their shame being discovered. No one talks about it, because the subject is too painful to approach. So they quietly support their son, hoping that in time the phase will pass, or because it is too painful to take the rather more brusque approach that Westerners might take.

Not that a more brusque approach would always work. Now, I don’t want to paint hikikomori as violent sociopaths or anything like that. The vast majority are simply apathetic and depressed. But anger at their condition can be part of the disorder, and it isn’t uncommon to go into a hikikomori’s room and find holes punched in the walls out of frustration. There are some accounts of hikikomori attacking or threatening parents who attempt to confront them about their problem.

Of course those are the extreme cases, where parents are rightly afraid of their children. In most cases, a kind of inertia takes over, and what started as a “phase” becomes a new normal, for both parent and child.

Culture Bound Syndrome, or Emerging Global Epidemic?

It might seem that hikikomori is a peculiarly Japanese phenomena, a culture bound syndrome that is limited to this particular time and place in history. While it is true that unique cultural pressures seem to make Japan particularly vulnerable to this disorder, there is growing evidence that people in other parts of the world, particularly in Western countries, are withdrawing from the world in the same way, if not in vast numbers like in Japan. This is a link to an article from The Japan Times where French researchers discuss the potential that hikikomori exist in their own country, although obviously by a different name and perhaps to this point unidentified. This article discusses a 30 year old man from Michigan who hadn’t stepped out of his apartment for three years. There have been reports from other European countries such as Spain, England, and Italy.

So what is going on here? Could it be that this is a social disease that is “spreading” globally, brought on by tough economic times and other cultural strains? Or is it something that has been around since the start, only we are just now beginning to identify it? Perhaps, it could be that hikikomori is truly a culture bound syndrome, and the cases in other countries are isolated incidents. Or perhaps the answer is some combination of the above; perhaps hikikomori is an emerging social disease, and Japan’s unique cultural factors have made it the proverbial “canary in the coal mine”.

The jury is still out among the experts. Right now there isn’t enough data, and with the nebulous nature of the term and the differences in cultural mores between East and West, not to mention among individual countries, further muddies the waters. While experts argue and do research, millions of Japanese families try to grapple with the problem of sons and daughters who just gave up, deciding that isolation was better than the harsh realities of the world outside their bedroom door.

Sources:

BBC News: Japan: the Missing Million

The New York Times Magazine: Shutting Themselves In

The Yale Globalist: Hikikomori

The Japan Times: French researchers seek raison d’etre of hikikomori

Hopefully everyone gets out of it and finds happiness

7/29/2025

interesting. In the west this disorder would be diagnosed under many different titles. none the less it is a seriois topic. Here it is portrayed as a form of depression and asocial behavour, but I have studied other articles pointing more towards self induced withdrawl due to interpersonal beliefs. for ex. a young man does not believe in such a rigid society and feels as tho he belongs somewhere else.a possible solution arrises for the so called 2030 problem, send/give them the opportunity to leave japan and try another culture. with the world the way it is today, it is easy and commom to compare your culture to others. sometimes you feel as tho u dont belong and see ur path in a distant vision.

I agree to some extent. I think that our emphasis simply looks at the problem from two different perspectives, but they’re pretty compatible. After all, if the individual has these beliefs that he doesn’t believe in the society and doesn’t belong, that will bring about depression, asocial behavior, and in the extreme withdraw from society. I think your solution to the 2030 problem is interesting, and certainly one I never gave any thought to. I think that with the large influence of western culture, the changing demographics in Japan, and other issues may mitigate the problem–or make it worse. No one can know for sure. Societies and their problems, after all, can’t be measured in a test tube. Maybe in fifteen years I’ll write a follow up post. Stay tuned! Haha