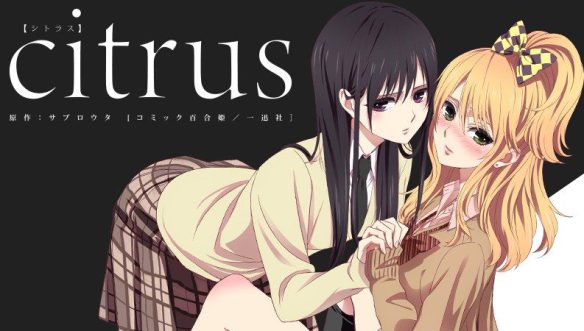

Citrus is the first yuri anime I’ve watched from start to finish. The story follows the fraught romance between two step-sisters Yuzu and Mei. As you can expect from anime, they share little in common. Yuzu is a fun-loving city girl while Mei is cold and by-the-books. Yuzu feels conflicted about her feelings. After all, she’s never felt attraction toward a girl, and her attraction toward her younger sister Mei troubles her. She feels the need to be a good elder sister but her love goes beyond sibling love. The pair takes steps forward in their relationship only to back off again. This is a common theme in other relationship-focused anime I’ve seen. It can annoy some viewers, but it is pretty realistic.

Citrus is the first yuri anime I’ve watched from start to finish. The story follows the fraught romance between two step-sisters Yuzu and Mei. As you can expect from anime, they share little in common. Yuzu is a fun-loving city girl while Mei is cold and by-the-books. Yuzu feels conflicted about her feelings. After all, she’s never felt attraction toward a girl, and her attraction toward her younger sister Mei troubles her. She feels the need to be a good elder sister but her love goes beyond sibling love. The pair takes steps forward in their relationship only to back off again. This is a common theme in other relationship-focused anime I’ve seen. It can annoy some viewers, but it is pretty realistic.

As I watched the show, I pondered the relationship of lesbian attraction and all-girls schools. In Citrus, it seemed such romances were common but still ridiculed. I wanted to know how much of this was fantasy and how much was based on reality.

Same-Sex Schooling and Lesbianism – Past Views

In the past, people in the West debated about the line between true homosexuality and situational-forced homosexuality. Girls who don’t define themselves as lesbian may have emotional and physical relationships while attending all-girls schools. But once they leave, they fall into heterosexual relationships and show no signs of wanting lesbian relationships (Steet, 1998).

In the past, people in the West debated about the line between true homosexuality and situational-forced homosexuality. Girls who don’t define themselves as lesbian may have emotional and physical relationships while attending all-girls schools. But once they leave, they fall into heterosexual relationships and show no signs of wanting lesbian relationships (Steet, 1998).

In a 1962 study “Homosexual Behavior in a Correctional Institution for Adolescent Girls,” 69% of girls ages 12-18 had been involved in homosexual behavior or “girl stuff” as the girls called any “sexually tinged relationship between two girls.” However, when they leave the institution many also left the girl stuff behind. The behavior, at least according to these past studies, doesn’t link with identity. However, women’s schools have a long literary tradition of female homosexual identity in the West. The first story traces to 1762 with “A Description of Millennium Hall.”

Lillian Faderman, a social historian, argued the modern lesbian identity dates to the Scotch Verdict Trial of 1811 where two teachers in an all-girls school—Miss Woods and Miss Pirie—were accused of engaging in “improper” displays of affection in front of their charges and corrupting morals. The teachers were acquitted because the judges didn’t want to admit to the reality of female-female sex (Blackmer, 1995).

Many girls feel like their peers assume they are lesbians just because they attend an all-girls school (Bloom, 2009). Much of this is because of how closely lesbian identity in the West associates with all-girls school literature and the Scotch Verdict. Yet, all-girls schools are strictly heteronormative.

All-Girls Schools and Forced Heterosexuality

Catholic schools dominate American single-sex schools, so the teaching of the church shapes most single-sex schools (Love & Tolsolt, 2013):

Catholic schools dominate American single-sex schools, so the teaching of the church shapes most single-sex schools (Love & Tolsolt, 2013):

Single-sex Catholic schools align fundamentally with Catholic doctrine in that students are seen either as male or female. Furthermore, single-sex Catholic schools are institutions that perpetuate socially constructed gender differences, normalize heterosexism, and through formal and informal school curriculum, ignore students who identify as queer.

According to the Catholic Church, acting on homosexual desire is a sin. Being a homosexual is a disorder, but as long you don’t act upon the feelings, you don’t sin. The church recognizes people are born queer, but it also expects them not to act upon this nature (Love & Tolsolt, 2013). Interestingly, we see a little of this in Citrus with Yuzu. In a few scenes, she feels wrong to feel and especially act on her attraction for Mei. Although she doesn’t conceptualize this as a sin, the act of kissing Mei weighs on her.

At these schools, dances can only happen with males and females, and even then contact is regulated. The church affirms homosexual identity and denounces discriminating against it even as it condemns acting upon that identity as a sin (Love & Tolsolt, 2013). Now this may seem contradictory, but the concept of original sin clarifies this. According to the idea, everyone inherits Adam and Eve’s sinful nature. Homosexuality comes from that nature according to the doctrine. Acting on such nature creates sin in this view. For example, you may have the love for gambling in your nature, but as long as you don’t act upon it, you don’t commit the sin. The doctrine defines how Catholic all-girl schools function.

The very reason behind same-gender schools is heteronormative. Same-sex education “rests on the premise that boys and girls will work better separately because they’ll ogle each other too much if they’re together.” Acknowledging desires outside of the heterosexual undermines one of the main reasons behind same-sex education (Savino, 2003). Some people worry that students will resort to homosexual experimentation without a heterosexual outlet, as if the heterosexual identity is the default. Savino (2003) continues: “In this model, the same-sex education system can admit lesbian behavior exists while simultaneously dismissing it as sublimated heterosexual desire!”

The very reason behind same-gender schools is heteronormative. Same-sex education “rests on the premise that boys and girls will work better separately because they’ll ogle each other too much if they’re together.” Acknowledging desires outside of the heterosexual undermines one of the main reasons behind same-sex education (Savino, 2003). Some people worry that students will resort to homosexual experimentation without a heterosexual outlet, as if the heterosexual identity is the default. Savino (2003) continues: “In this model, the same-sex education system can admit lesbian behavior exists while simultaneously dismissing it as sublimated heterosexual desire!”

Studies on the effectiveness of same-sex schools appear mixed. They appear to help minorities. The schools appear to remove distractions caused by the opposite gender, allowing students to be more open with each other and with their teachers, but trusting teacher-student relationships matter more (Hubbard, Datnow, 2005).

Bullying

In Citrus, Yuzu worried about bullying in a few scenes. The same-sex school environment changes the nature of bullying. Girls show more relational-aggression than boys. Boys show more physical aggression. But because these are normal patterns, victimization happens when the opposite happens (Velaquez, 2010):

Among boys, victimization was associated with relational aggression but not physical aggression; conversely, among girls victimization was associated with physical aggression and not relational aggression.

Velaquez (2010) found girls in same-sex schools associate physical aggression as more negative than relationship bullying more than girls from mixed-sex schools. These schools seem to normalize the perception of physical aggression for both genders. This is likely because its seen more often with guys around than when there are all girls around. Although I have to admit that anecdotally I’ve seen more pushing and physical aggression from girls than from guys. Any behavior that deviates from the norms of peers attracts bullying, which explains Yuzu’s worry.

Conclusion

I’ve focused on the US. This is partially because it’s the information I have and partially because anime is an international medium. A good portion of Japan’s school system was modeled after the West’s systems. Because of this, looking at US research can give us some insight as to the reality behind the same-sex school in Citrus. Japan has a long unacknowledged history of lesbianism. Such encounters appear in various shunga and hinted-upon in Heian period literature. Yuri stories descend from these.

I’ve focused on the US. This is partially because it’s the information I have and partially because anime is an international medium. A good portion of Japan’s school system was modeled after the West’s systems. Because of this, looking at US research can give us some insight as to the reality behind the same-sex school in Citrus. Japan has a long unacknowledged history of lesbianism. Such encounters appear in various shunga and hinted-upon in Heian period literature. Yuri stories descend from these.

It looks as if the all-girls school in Citrus has some basis in reality. Same-sex schools are mostly heterosexual as an environment, but they can encourage limited homosexual relationships and experimentation. Many of these students aren’t lesbians. They could be considered bisexual, perhaps, or just situational-seeking relationships as some used to believe. So some of the side hints to this in the anime can be considered realistic.

Really, all of this just depends on the individual. When I was researching, some lesbian students found all-girl’s schools oppressive. Other interviews found them a welcome place to be themselves. Heterosexual girls felt the stigma of the literature surrounding all-girls schools. This combined with the fact they had few encounters with boy to make it difficult for them to relate to boys. The schools benefit some, and it hurts others.

As for Citrus, I found the anime interesting. Yuzu’s conflict backpedaled enough to feel realistic. Relationships don’t advance in a linear way, and the story does a good job showing that. Because it’s the first yuri I’ve watched to the end, I can’t comment how it compares. The fan-service remains standard fare for anime. You’ll see the usual accidental walk-ins during showers. Citrus shows topics like female masturbation as normal and common with how briskly it passes over them. If anything, the series felt too fast. Many conflicts and problems resolved too quickly. I was glad to see no one was an airhead. Even Yuzu had a sharp mind when she applied herself. She just didn’t have the interest to do so until she met Mei. Even the side characters felt intelligent.

The story isn’t the best (it’s uncomfortable at times), but anime lately have learned toward mediocre stories and unlikable or flat characters. The characters in Citrus suggested they have more depth than many characters in Spring’s anime line-up.

Reference

Blackmer, C. E. (1995). The finishing touch and the tradition of homoerotic girl’s school fictions. Review Of Contemporary Fiction, 1532.

Bloom, Adi (2009) Tart or Lesbian? How pupils at all-girls primaries live in fear of labels that stick. The Times Educational Supplement. No. 4841. 12.

Coren, Sidney & Luthar, Suniya. (2014) Pursuing perfection: distress and interpersonal functioning among adolescent boys in single-sex and co-educational independent schools. Psychology in the Schools 5 (9).

Hubbard, Lea & Datnow, Amanda (2005) Do Single-Sex Schools Improve the Education of Low-Income and Minority Students? An Investigation of California’s Public Single-Gender Academics. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 36 (2) 115-131.

Love, Bettina & Tolsolt, Brandelyn (2013) Go Underground or in Your Face: Queer Students’ Negotiation of All-Girls Catholic Schools. Journal of LGBT Youth. 10. 186-207.

Savino, Kathleen (2003) Thighs Are Not Attractive, Ladies! Homophobia and Same-Sex Education. Off Our Backs. 33 (11/12) 25-28.

Steet, L. (1998). Girl Stuff: Same-Sex Relations in Girls’ Public Reform Schools and the Institutional Response. Educational Studies: A Journal In The Foundations Of Education, 29(4), 341-58.

Velaquez, Ana Maria & others (2010) Context-Dependent Victimization and Aggression: Differences Between All-Girl and Mixed-Sex Schools. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 56 (3) 283-302.