As for the Gossamer Lady herself, we know her father was Fujiwara no Tomoyasu. a provincial governor, and she had a brother named Nagato who was a poet. When she was 18, she was an accomplished poet herself and one of the “three beauties of Japan,” which lead to Kaneie’s interest. In fact, her work was included in the later One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets compilation.

Throughout the Gossamer Journal, the Gossamer Lady’s voice rings with personality and with sadness. In the poetic exchanges she included, she wasn’t afraid to show a sharp tongue. In one exchange of courting poems, as was the custom of the time, with Kaneie she lets him have it for his reputation as a womanizer. He had just started to try to woo her into marrying him. Here is the translation:

Autumn approached. In a postscript to one of his letters, Kaneie wrote, “It distresses me that you should seem so firmly on your guard. I try to put up with it, but what can be the reason for my plight?” [His poem:]

I live among men

where the cry of the stag

does not reach one’s ears.

Is it not strange that my eyes

refuse to close in sleep?

My reply was simply this poem. with the comment, “Strange, indeed!””

I had never heard

that you would be likely to lie

thus sleepless alone,

even if you were dwelling

near the peak at Takasago.

Ouch!

Of course, some of her writing at this section of her journal is the expected coyness women were supposed to have when being courted. However, the above poem certainly was more than acting coy. His known infidelity reappears throughout the first book. She never paints him in a completely negative light, however. She even wonders if her desire for him to always remain with her is misplaced. The text is raw and quite human. The Gossamer Journal isn’t a romance despite the moments of romance. She does, after all, come to love Kaneie for a time. The Gossamer Lady explains her purpose at the beginning:

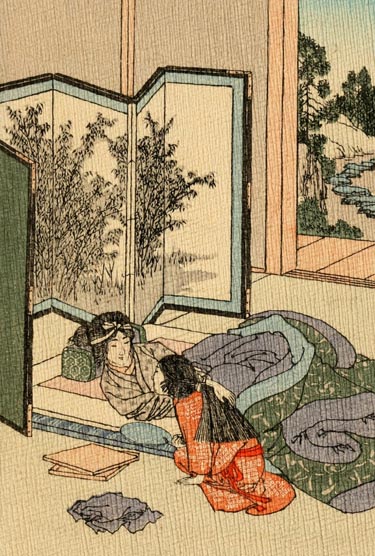

There was once a woman who led a forlorn, uncertain life, the old days gone forever and her present status neither one thing nor the other. Telling herself that it was natural for a man to attach no value to someone who was less attractive than others and not very bright, she merely went to bed and got up day after day. but then it occurred to her, as she leafed through the many current tales of the past, that such stories were only conventional tissues of fabrications, and that people might welcome the novelty of a journal written by and ordinary woman. If there were those who wondered what it was like to be married to a man who moved in the very highest circles, she might invite them to find the answer here. Her memory was not good, either for the distant past or for the more recent events, and she realized in the end that she had written many things it might has been better to omit.

We know she was quite an intelligent woman and had excellent memory despite (because of) this introduction. However, she was right about the novelty of a published journal written by a woman. This tradition, which she helped established, of women writing publishable, yet raw, memoirs and poems remains one of the most fascinating pillars of Japanese literature. Some sections of The Gossamer Journal teem with her emotions. Such writings helped established the later concept of wabi-sabi, the perfection of the imperfect, the happiness of sadness. Of course, I’m not saying she was happy.

In many of her sections, the Gossamer Lady appears lonely. She was often trapped in her home with only a few servants and the young Michitsuna for company. If you read the Confessions of Lady Nijo (who lived long after the Gossamer Lady), you see a similar loneliness and boredom. While we are fortunate these women were bored–we wouldn’t have had their writings otherwise–their pain is palpable. Fortunately, the Gossamer Lady established a friendship with Tokehime, and they often exchanged poems of friendship along with other news, such as this section:

According to the gossips, Kaneie was also staying away altogether from Lady Tokihime, the consort who had borne him so many children. I sent her a solicitous message, in the thought that her position was even worse than mine. Because it happened to be around the Ninth Month, I added this poem to my expressions of sympathy:

Even though the web

long trodden by the spider

may vanish in the sky,

I trust the wind if need be

to tell you of my concern.

Her reply was cordial:

When I consider

how it causes things to change,

I find it odious–

that wind you have enlisted

to tell me of your concern.

Unable to maintain my pose of aloofness forever, I did see him occasionally. And so the winter arrived. Living with the baby as my sole companion, I found myself murmuring the old poem. “What is the reason? I long to question the whitefish gathered at the weir.”

According to the translation I read, Tokihime’s response included a double play on the Japanese words. Her poem can also be read as “I’ll dislike the wind if it deprives me of your friendship by causing your feelings to change.”Japanese literature enjoyed these puns and play on words, which is why poetry could appear to be nice but actually cut. In this case, Tokihime’s seemingly rough reply–that she doesn’t like the the Gossamer Lady’s message of concern–is actually a reaffirming of their friendship. This reading between the lines requirement appears throughout Japanese literature, particularly in the Tale of Genji.

The title of the work, The Gossamer Journal, strikes me as lovely and sad. Gossamer references sheer delicate fabric and the fineness of spider webs caught on bushes as they gather the dew. Both show a delicateness that defies and invites touch, knowing that such a touch would ruin them. Another translation of the Japanese word, the translation actually favored by scholars, is mayfly. The Mayfly Journal works just as well as gossamer; both point to a short, ethereal life. Gossamer is a little more poetic sounding in English, however. The Gossamer Lady’s reflections and writings have a similar feeling. Beautiful but combined with the knowledge that it all ends at a touch. As you read, you get to see a little of the woman who lived over 1000 years ago. The glimpse, gossamer as it is–fluttering like the short life of a mayfly, offers a view that history lacks. The fact we don’t know her name, that we only know her as Michitsuna’s Mother, underlines the gossamer nature of high-class women and the invisibility of the low-classes. There is a feeling of wrongness as you read. You know her thoughts and feelings, but you don’t know her name. Her see her wit and skill with words. You can see the gossamer strands of her life, not really any different from our own.

References

Craig McCullough, Helen (1990) Classical Japanese Prose. Stanford University Press.