Artists used carved wooden blocks to mass produce ukiyo-e. This allowed most people to afford them, and these woodblocks quickly became a form of entertainment. The popularity and production method of ukiyo-e makes them confusing for collectors. First, popular works wore down the wooden blocks, forcing the publisher to carve more. Publishers sometimes used this chance to change their designs. It is also not unusual for a single print to use over 20 different blocks. So when a single block wears out or cracks, another one has to be carved. A team sits behind a print, but we usually know the name of the only designer: Hiroshige, Hokusai, etc.

This begs the question, what is an original print? Normally original works of art have more value than prints, but all ukiyo-e are mass-produced prints. You can consider original prints as those made during the artist’s lifetime (do we mean the designer, carver, or inker?), but if the publisher uses the same wooden blocks to make a modern print, is it an original? Likewise, if you make a print with 100+ year old blocks, but one had been recarved recently, is the print original?

David Bull, a modern ukiyo-e carver, explains how the idea of original doesn’t really count for prints. He argues that publishers own the designs and often use old blocks. From this perspective, all prints made using traditional techniques, are originals. It might be more useful to consider posthumous printing against prints done during the designer’s lifetime. Age tends to make items more valuable. But for casual collectors, the question of “authenticity” isn’t that important. After all, I’ve visited museums that showcase later reprints of ukiyo-e. I own several that would likely match the museum’s criteria for display because of their age, yet they are not “originals.” For example, I own several Hiroshige works dating to 1896 that are in good condition. Yet I also own a Hokusai dating to 1820 that no museum would want because of its condition.

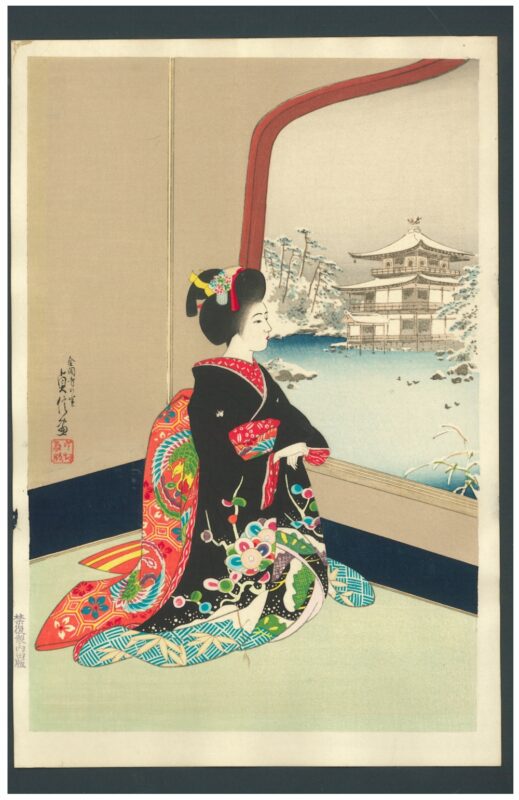

When casually collecting, you have to decide what you want to collect and what conditions you can tolerate. I view the Hokusai I own as a rescue. Luckily, the question of authenticity and condition allows you to buy old works for reasonable prices. I paid $40-200 at auction for each piece in my collection. They aren’t in pristine condition, nor are they all “authentic,” that is, printed during the designer’s lifetime. But they are all “original” woodblocks. You can’t own famous oil paintings for anywhere near that price. The mass produced nature of woodblock prints works in your favor. You will find terribly overpriced works for auction, but if you are patient and are willing to buy lesser conditions, you can find deals. For example. I own a Hiroshige snowscape that auctions for between $500-$1500 in pristine condition (I’ve also seen it for $5000). The one I own has a small tear from the corner and a little foxing. I paid $50 at auction.

Foxing is when paper deteriorates as it ages. It creates red-brown stains and spots. Because I’m a librarian and see foxing all the time, I find it quite charming. It also works with the idea of wabi-sabi. Luckily, foxing can be controlled by careful storage of the work.

I collect landscapes. I don’t care for images of actors or wrestlers, although I own a few works of maiko and geisha. You have to decide what works you prefer. You can also buy shunga and even entire books of woodblock prints. You also have to decide on the sizes you want. Many later reproductions are printed on quarter sheets. Because of their small size and lack of “authenticity,” they don’t cost much, and you can find them for sale in themed lots. When you buy prints, beware high-end digital prints. Sometimes these are printed on washi paper. A true woodblock print will have its inks bleed through and feature embossing from the ink-transfer process. When you touch a woodblock print, you can feel the ridges of the blocks pressed into the paper.

I prefer oban sizes. This size was among the most common in the Edo period, and it displays well. Artlino has a wonderful breakdown of ukiyo-e sizes.

Speaking of display, I don’t recommend framing originals. With proper framing, ukiyo-e can survive for years, but sunlight fades them. I prefer to make high-quality color copy and frame that. That way, I don’t have to worry about the print fading or otherwise aging. I also save money on framing. I buy black Walmart and Dollar Tree frames. Professionally framing the original print can run hundreds of dollars depending on the glass and other preservation materials you choose. I also scan each woodblock as an image so I can easily print another one if I need to.

I store the originals in archival sleeves designed for storing artwork. The acid-free paper and clear, non-reactive plastic protects them and slows foxing. I keep the sleeves in an archive art box to protect them from sunlight. Finally, I store the box in a dry, inner closet so the environment stays relatively constant. It’s not a complete archive solution, but it works on a budget. A single box can hold many prints, and a single sleeve can protect several smaller prints. Don’t stack the prints inside the sleeve, however. Large prints need their own sleeves.

If you want to collect original art but aren’t a millionaire, ukiyo-e offers a great option. As with any collectible, prices will rise and fall with demand. I don’t recommend buying ukiyo-e as an investment. Their mass-produced nature keeps them from holding value outside of a few pristine, authenticated originals. As with anything, read and study before you jump in. Books dedicated to ukiyo-e provide a great starting place for learning what you like and don’t like about the medium. You might like wrestlers but not landscapes, for example. People still make prints in the traditional way but with modern topics. David Bull’s work is quite nice. I appreciate the chance to own sheets from Japan’s history, and that, in particular, is the pleasure of collecting ukiyo-e. If you aren’t careful, you home will quickly look like a museum!