Japan, like nearly all nations. has a history of slavery. Many Western historians in the past believed the concept of freedom was imported to Japan from the West. This misplaced, Western-centric view states the West wrestled with its heritage of slavery and awoke to human rights and freedom before showing the rest of the world. This view is false, as we shall see.

Japan, like nearly all nations. has a history of slavery. Many Western historians in the past believed the concept of freedom was imported to Japan from the West. This misplaced, Western-centric view states the West wrestled with its heritage of slavery and awoke to human rights and freedom before showing the rest of the world. This view is false, as we shall see.

Japan has long been a destination country for slaves, especially sex slaves, and still remains that way today (Botsman, 2011; Queen, 2015). Human trafficking to Japan traces to at least the 7th century. The lowest class of people within Japan were legally bought and sold. However, it was illegal to force a Japanese person into this class by kidnapping them, but this protection, such as it was, didn’t extend to foreigners. The system was disbanded during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) (Queen, 2015).

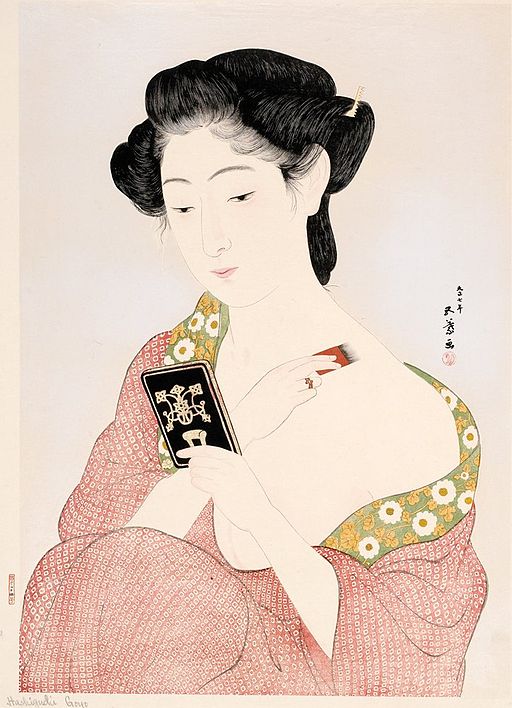

After a brief respite from institutional slavery–don’t doubt that slavery still existed during the Kamakura period–the Jesuits brought it back to Japan with a focus on exporting Japan’s lowest classes. Portuguese sailors in the 1500s found cheap slaves within Japan and high demand back in Europe, especially for Japanese women (Botsman, 2011; Queen, 2015). The Jesuits exported slaves from Nagasaki. Some of the first Japanese to enter Europe were women destined to be sex slaves.

However, this backfired on the Jesuits when the Toyotomi Hideyoshi used the slave trade as evidence of Christianity’s negative influence upon Japan. He issued a series of expulsion orders against Jesuit missionaries and a formal ban on the sale and export of Japanese slaves. This wasn’t because he had moral qualms about the slave trade. Rather, he wanted to build a stable society, and slavery drained the country of potential workers. The ban of 1587 prohibited the export of slaves and the domestic slave trade. Slavery more or less ceased in Japan by the end of the 1600s (Botsman. 2011). So much for the Western narrative, right?

Slavery again became a problem at the end of the Tokugawa period, if in a different form. When Japan opened to the world in 1858 with the Harris Treaty, the problem of human trafficking also returned. The West began to institute a cooly system, cheap and exploitable labor, within Japan’s poor and lower classes. These workers, who could be considered slaves or debt-bondage labor, worked the plantations and other areas in the Western colonies, such as the sugar plantations of Hawaii (Botsman, 2011; Moen, 2012). During the Meiji government’s early years, domestic debt bondage became more visible within the sex trade. Japan still fights this problem within its sex industry, but I will examine that problem in another article.

The Meiji government saw the existence of slaves within Japan, through the cooly system and sex slavery, as shameful. The government eventually issued the “Emancipation Edict for Female Performers and Prostitutes” to liberate women and girls in the sex trade. When the brothels resisted and demanded financial compensation for their losses, the Meiji government pointed to the Tokugawa slavery bans, like those of Hideyoshi, as evidence that the brothels operated illegally (Botsman, 2011).

The edict didn’t ban prostitution. A new legal framework for the world’s oldest profession developed. The edict was also overshadowed by the 1871 “Order to Abolish Outcaste Status Designations.” This order removed Japan’s outcaste system–outcaste were the classes that the slave and cooly system exploited–by raising those people to the level of commoner, reducing their level of legal exploitation. This move also removed the legal discrimination they faced because of their low social status and professions. It also removed their status as lowly and impure within the society’s framework.

The Penal Code of 1907 finished the job of these edicts by forbidding human trafficking. This code remains in effect (Queen, 2015). Of course, illegality never stops behavior. Japanese girls remain victims of human trafficking and debt bondage within Japan’s sex industry (Moen, 2012). Despite the Penal Code of 1907, the Japanese government engaged in sex slavery during World War II. Thousands of young girls and women were forced to serve as sex slaves for the Japanese military. Euphemistically called “comfort women,” the military accelerated the program after the The Rape of Nanking. The Rape of Nanking, also called the Nanjing Massacre, happened during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Imperial soldiers spent 6 weeks looting, killing, and raping the residents of Nanjing, China. The period included the march from Shanghai to Nanjing. According to Queen (2015), “[i]t was a common belief that soldiers should not die as virgins, and many thought that sex before battle protected soldiers against death.” The Japanese military viewed the comfort women program as a way to stop future massacres and rapes.

Comfort women were mainly from Japan’s Imperial holdings. including Burmese, Chinese, Dutch, Filipino, Indonesian, Korean, and Taiwanese women. An estimated 80% were Korean. Japanese women were expected to stay home and have children (Queen, 2015).

After World War II, the new Japanese constitution established human rights for its citizens. In 1950, those rights were extended by the Japanese Supreme Court (Queen, 2015): “[I]t should be recognized that any person who stays in Japan is entitled to human rights which he or she should naturally have as a human being even if his or her entry into the country was illegal.” In 1956, the Japanese Diet passed a law that ended all licensed prostitution in Japan, but it left consensual sex work open, which also left open the problem of debt bondage.

Modern day slavery focuses on forced prostitution with an estimated 75-80% of cross-border human trafficking. Because of Japan’s sex industry, enabled by the narrow definition of sex in the 1956 law, Japan remains a destination country for sex slaves and continues to struggle with domestic debt bondage (Moen, 2012).

As you can see, past Western historians were wrong about the idea of an “enlightened” West teaching Japan the sins of slavery. Japan banned slavery in the late 1500s and had an off-and-on-again relationship with the practice since. For perspective, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, 275 years after Japan issued a ban on slavery. Japanese slavery didn’t focus on Africa like the Western powers of the time. Orientalism, the portrayal of Asian cultures as exotic, undeveloped, yet inspiring, helped fueled the Portuguese and Jesuit trade of Japanese women to Europe. Their exotic nature–compared to European ideals of the time–would’ve acted as status symbols for those who could afford them. This likely added to the stubborn idea of the sexy, submissive Japanese woman that remains in the US and elsewhere in the West. Of course, media doesn’t help matters now, but centuries of thinking can be subtle and hard to excise.

Slavery has been a fact of most cultures of the world, casting a legacy that nations still contend with today. For the US, it influences the treatment and welfare of black communities. For Japan, slavery remains a problem within its sex industry and the unresolved comfort women problem. The Japanese government doesn’t want to admit to the program. The nations have managed to push slavery to the shadows of illegality and no longer embrace slavery as a system. However, human trafficking remains a problem that nations can only address together.

References

Botsman, Daniel V (2011). Freedom without Slavery? “Coolies,” Prostitutes, and Outcastes in Meiji Japan’s “Emancipation Moment.” American Historical Review, 116(5), 1323–1347. https://oh0164.oplin.org:2085/10.1086/ahr.116.5.1323

Dinan, K. A. (2002). Trafficking in Women from Thailand to Japan. Harvard Asia Quarterly, 6(3), 4–13.

Moen, Darrel (2012) Sex Slaves in Japan Today. Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies 44. 35-53.

Queen, E. M. (2015). The Second Tier: Japan’s Stagnation in the Fight against Sex Trafficking. Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, 25(3), 541–570. https://oh0164.oplin.org:2085/10.18060/7909.0030

I found a small typo:

Hideyoshi “issued a series of expulsion orders against Jesuit missionaries and a formal band on the sale and export of Japanese slaves.”

• “band” should be “ban”.

Corrected. Thank you!

prostitution and human trafficking go hand in hand, ”worlds oldest profession” is a slogan used by pimps and lib johns to normalize it and turn more women and girlies into public property for degenerate men.

It is a sad and ugly part of history that we can’t seem to evolve beyond. The human mind takes far too much time to evolve.