Japan’s sex industry exists because of the narrow definition of prostitution found in the 1956 law that ended licensed prostitution in Japan. Namely, the law defines sex as penile-vaginal intercourse which allows the legal offering of most other sexual services (Koch, 2016). In turn, the existence of the sex industry encourages human trafficking of children and women.

Japan’s sex industry exists because of the narrow definition of prostitution found in the 1956 law that ended licensed prostitution in Japan. Namely, the law defines sex as penile-vaginal intercourse which allows the legal offering of most other sexual services (Koch, 2016). In turn, the existence of the sex industry encourages human trafficking of children and women.

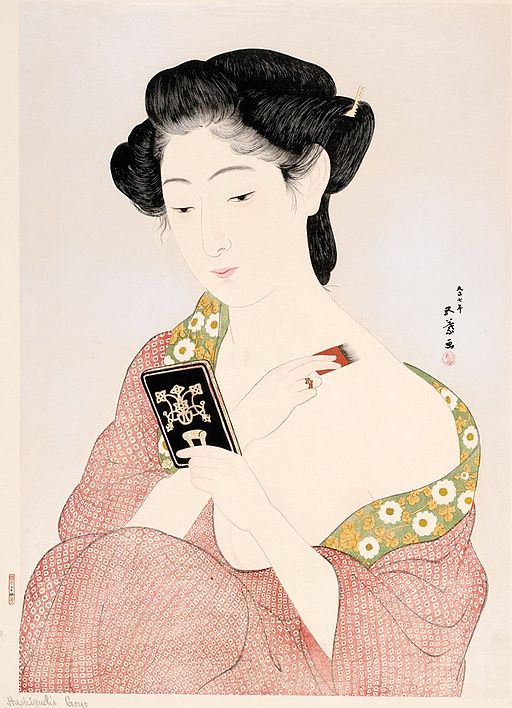

Japan’s sex industry has existed on record since the 7th century, and sex slavery has remained a part of it. Portuguese sailors in the early 1500s purchased Japanese women to sell in Europe. Some historians believe the first Japanese to step onto Europe were slaves (Botsman, 2011). During the Edo period, red-light districts like the Yoshiwara appeared to offer state-licensed sexual services. Girls were sold into indentured prostitution by their families to pay off debts or ease the strain on the family’s food supply. Wives would also be forced into prostitution to pay off her husband’s debts.

Today, between 75-80% cross-border human trafficking involves women and children destined to work in the worldwide sex industry: “…women provide a good cheap labor for the slave industry because selling a woman is no great loss to a society” (Moen, 2012; Queen, 2015). Japan is a destination country for sex slaves. Japan remains a hub for the production of child porn and has a variety of sex services, including brothels, hostess/host clubs, escort agencies, strip theaters, soaplands, and other venues. Many of these are owned by yakuza (Moen, 2012).

The yakuza used to deal internationally to set up sex tour packages and source girls for their own businesses (Moen, 2012):

The involvement of the Russian or the Italian Mafia, the Chinese Triads or the Japanese Yakuza, as well as other organized groups such as Ukranian and Albanian organized crime networks is a well-known fact. Therefore, many trafficking victims, both foreign and Japanese, are reluctant to seek help from authorities for fear of reprisals by their traffickers, who are often members or associates of Japanese or foreign organized crime syndicates.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the yakuza organized sex tour packages for wealthy Japanese men with destinations in Taiwan, South Korea, Philippines, and Thailand (Dinan, 2002). However, as Japanese feminist groups protested this and brought it to light, demand for these tour packages decreased, driving the yakuza to import women from those countries and building networks with other organizations across the world. This also drove the yakuza to look at Japanese women as targets.

Foreign women in the sex industry often struggle with debt bondage and other forms of manipulation. Debt bondage involves recruitment costs, travel documents, travel expenses, food, accommodation, bribery charges, purchase price, and high levels of interest. This is designed to make the debit impossible to pay back. Most women are led to believe the work is in a different industry. The Polaris Project Japan describes their treatment (Moen, 2012):

Once the women and children are brought into Japan, a process of ‘seasoning’ or breaking them down occurs, usually consisting of gang rapes, beatings, forced drug administration, and informing the victims of debts they now owe the traffickers and how they must pay them.

Of the countries the yakuza targeted, Thailand was the most important during the 1990s for the pink-light district of Koganecho in Yokohama. The women wore costumes while they solicited: high school uniforms, china dresses. bikinis, and other costumes. Next to Koganecho, in Wakabacho, businesses catered to the needs of the Thai sex workers: karaoke bars, food delivery, dance clubs, grocery stores, video stores, and gambling houses. A little Bangkok appeared where Thai women could hang out with their friends, boyfriends, and regulars. In this way, the importing of sex workers changed the local culture of this district and others across Japan (Yoshimizu, 2015). It’s easy to forget that these women often had lives outside their professions, forced into the profession or not.

Japanese girls are also victims of manipulation as foreign slaves become more difficult to smuggle. However, many Japanese sex workers are willing workers. Remember how Japanese daughters and wives were responsible for family debts in the past? Many Japanese women enter the sex industry out of a similar sense of responsibility toward their families. The sex industry is one of the most lucrative, short-term work available for women, even though it remains stigmatized and seen as a sacrifice for the family (Koch, 2016).

Koch (2016) interviewed one worker named Risa who entered the sex industry to financially support her elder sister’s medical degree. It was her parent’s dream for the elder sister to become a doctor, so Risa helped pay for this. She worked at a soapland — an erotic play center focused on bathing with a sex worker who offers sexual services during and after an elaborate bath and massage. Services can include illegal intercourse too. When Koch wrote her paper, soaplands offered some of the highest wages in Japan’s sex industry, but workers also viewed them as a last resort. Women usually preferred businesses that revolve around “lighter” services such as oral sex, manual stimulation, and costume play.

Women such as Risa, whose economic and educational background may at first seem incommensurate with their narratives, reiterate a rationale of selfless engagement in sex work in order to locate themselves within a moral position of filial sacrifice and dutiful daughterhood. Moral expectations around what women’s labor should be for structure what sex workers can say about their motives. This illustrates how economic explanations are never straightforward and are incomplete outside of ethical and moral frameworks. What gets obscured by such narratives, however, is the reality that there are many women working in the sex industry who, like Risa, are middle-class and even college-educated, and who find the financial rewards and flexibility of sex industry labor appealing in contrast to other options.

The filial aspect of the sex industry, as Risa’s case suggests, is still around. Japan’s focus on family duty extends all the way through their culture. But this expectation also translates into a moral shield for working within the sex industry for reasons Koch discusses. Legitimate moral labor is framed as work for a sister or a child and not for one’s own comfort. Male work has the same moral component, aimed toward the family as well, but in a different way than women’s labor is.

Japan’s sex industry can offer every service short of penile-vaginal intercourse. In 2016 (Koch) there were about 31,500 legal sex businesses across Japan. Japanese culture retains some tolerance for male pre-and-extra-marital “play” while women still face ridicule for being a sex worker. The requirements of long work hours and low pay in regular work make the sex industry appealing for single mothers and other women who need more short-term income and flexible hours. Human trafficking and sex slavery and the influence of organized crime like the yakuza remains just under the glitzy facade. The human aspect is important to remember when considering the selling of skin. These women, such as the Thai woman I summarized, have feelings and friends and hopes. Sometimes they develop friendships and relationships with regulars. Moen (2012) interviewed a young Thai woman who was taken to Japan as a sex worker. She eventually returned home:

“I now twenty-two year old. I go Japan five year ago. My agent tell me I make good money in Japan so I go because my family very poor and need money to live. I get Tokyo airport and Japanese man meet me at airport. He take my passport and I get in car and we drive four, maybe five hour. Where I am, where I go, I do not know. We get to some city late night and he take me inside club from back door. I meet older woman inside, she tell me she “mama-san ” and I have to work to pay back her 3,000,000 yen..I say no, that mistake. But she say, no mistake.

I cry and cry but no good. I want to go back to Thailand but no can do until I pay back 3,000,000 yen. I work there every day very hard. I give sex to 10 or 12 men every night. Some men mean and they hit me. Some men drunk and they yell me. Some men no use condom. Some men do terrible things to me I no can tell you. But I know I must to go back home so I do what they want me to do. I no choose. I work there for one year and mama-san say now I get paid for work because 3,000,000 yen paid back. I only work one month more to make money for fly to Bangkok. I no like Japan. I no like Japanese men, very mean. I no human being in Japan. I no see Japan outside of club because they keep me inside all time.”

Japan’s overt sex industry, sometimes hidden behind girls mimicking anime characters, remains a problem. The industry also extends into printed materials, such as hentai and skin magazines, that encourages men to view women in objectified ways. In turn, this view stokes demand for the sex services I’ve sketched. Prostitution can never be eliminated, but it can be reduced by raising men (and women) to be respectful and self-controlled and avoid hedonism. It can be reduced by changing the economic circumstances that encourage women to seek the profession when they lack alternatives.

References

Botsman, Daniel (2011). Freedom without Slavery? “Coolies,” Prostitutes, and Outcastes in Meiji Japan’s “Emancipation Moment.” American Historical Review, 116(5), 1323–1347. https://oh0164.oplin.org:2085/10.1086/ahr.116.5.1323

Dinan, K. A. (2002). Trafficking in Women from Thailand to Japan. Harvard Asia Quarterly, 6(3), 4–13.

Koch, Gabriele (2016) Willing Daughters: The Moral Rhetoric of Filial Sacrifice and Financial Autonomy in Tokyo’s Sex Industry. Critical Asian Studies. 48 (2) 215-234.

Moen, Darrel (2012) Sex Slaves in Japan Today. Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies 44. 35-53.

Queen, E. M. (2015). The Second Tier: Japan’s Stagnation in the Fight against Sex Trafficking. Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, 25(3), 541–570. https://oh0164.oplin.org:2085/10.18060/7909.0030

Yoshimizu, Ayaka (2015) Bodies that Remember: Gleaning scenic fragments of a brothel district in Yokohama. Cultural Studies. 29 (3) 450-475.

Need to work sex movie