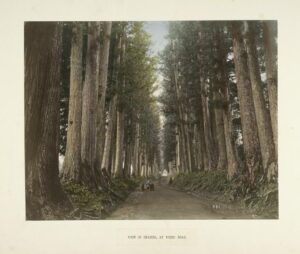

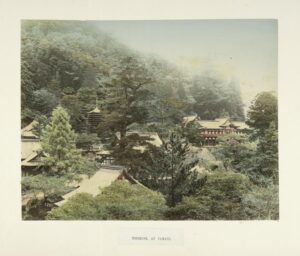

The mid-to-late 1800s marked a shift in Japanese history: the Meiji Restoration. The old guard, the Tokugawa Shogunate, with their isolationist attitudes were overthrown, and Japan began a miraculous modernization movement. When you consider the shift, it is amazing. Japan went from being primarily agriculturally-based in 1853 when Commodore Matthew Perry of the US forced Japan to open to trade to the modernized military juggernaut of World War II just 86 years later. Most of us focus on military developments during this time, but the arts also flourished. Photography entered Japan just as woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, were the main form of popular art. Ukiyo-e laid the groundwork for Japanese photograph and their lovely hand-colored work.

The mid-to-late 1800s marked a shift in Japanese history: the Meiji Restoration. The old guard, the Tokugawa Shogunate, with their isolationist attitudes were overthrown, and Japan began a miraculous modernization movement. When you consider the shift, it is amazing. Japan went from being primarily agriculturally-based in 1853 when Commodore Matthew Perry of the US forced Japan to open to trade to the modernized military juggernaut of World War II just 86 years later. Most of us focus on military developments during this time, but the arts also flourished. Photography entered Japan just as woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, were the main form of popular art. Ukiyo-e laid the groundwork for Japanese photograph and their lovely hand-colored work.

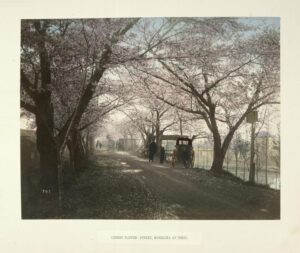

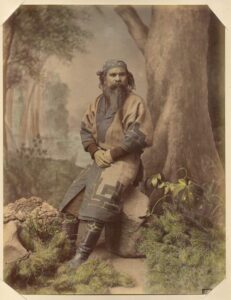

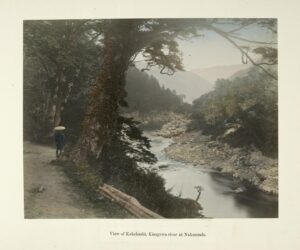

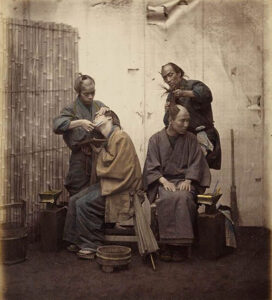

Photography entered Japan through Nagasaki, the only trading port where the Tokugawa government allowed foreign traders, in 1848 (Gartlan, 2006). In 1854, photographer Eliphalet Brown Jr. return with Perry and took the first known photograph in Japan (Luppino, 2009). Soon after Japan opened, other photographers invaded, and they discovered a culture open to their art. The subjects of ukiyo-e–actors, geisha, sumo wrestlers, and landscapes–became popular subjects for the new tourist photography market. The port city of Yokohama became the center of this new industry. Almost 90% of photographs exported from Japan at the time came from Yokohama (Luppino, 2009). At the time, Westerners were fascinated by Japanese culture. Photographers saw the business opportunity of providing souvenir photos for tourists and selling photo books to people in Europe who weren’t able to travel to Japan. Felice Beato was the first to capitalize on this interest.

Felice Beato, Father of Japanese Photography

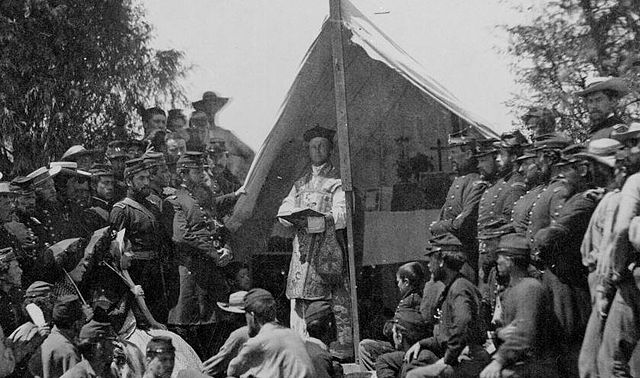

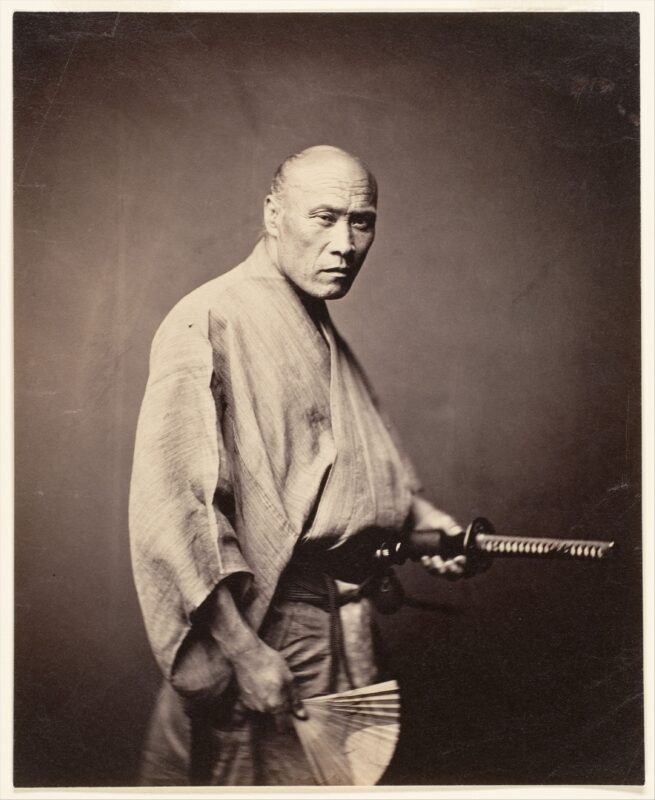

Born in Corfu, Italy Felice Beato (c1825-1907) became the first photographer to specialize in war photography. We know little about his early life, but he was known as an eccentric who favored colorful language and business scheming. After learning photography from his brother-in-law James Robertson–who married Beato’s sister in 1855, Beato joined Robertson on an expedition to photograph the Crimean War between Britain and Russia. The next year, Robertson sent Beato back to photograph the war’s aftermath, where Beato started his practice of arranging corpses for emotional effect. Robertson and Beato used a secret dry-plate method that allowed them to photograph in the field. The wet-plate photography at the time wasn’t suited for weather conditions and other issues associated with war photography. Their new technique allowed them to do what previous photographers couldn’t. Robertson and Beato traveled around the Mediterranean until Beato left for India in 1858 to photograph the massacre of Indian rebels fighting against Britain. Over the next 2 years, he worked as the semi-official photographer for the British army.

In the same year, Chinese tried to stop Britain’s export of Indian opium into China, and the British retaliated by attacking and sinking most of the Chinese navy and invading China. Beato traveled with the army throughout its campaign, taking photos of the aftermath of the war. His 100 photographs are the only surviving images of China before the 1870s. After returning to London, Beato decided to travel back to the Far East and settled in Yokohama, Japan for the next 20 years where he made several hundred images of Japan. Beato’s photos ranged from Japan’s landscape and architecture to its people. Considered the father of Japanese photography, his work provided the only record of the country during the 1860s. He retained his interest in war photography: in 1871, the United States Navy appointed him the official photographer for their attack on Korea. After losing all of his money at the Yokohama silver exchange’s speculative market, he settled in Mandalay, Burma where he founded a photographic studio and sold local arts and crafts through the mail. He died in Burma in 1907 (Wilson, n.d; Gartlan, 2006).

Beato’s Influence on Japanese Photography

Beato’s studio set the standards for Japanese photography at the time, and his work shaped how Europeans and Americans viewed Japan. His work also shaped how Japan developed a new self-identity as the country transformed from a feudal society to an industrial society. Beato’s photographs helped Japan become aware of its appearance to the rest of the world. Luckily, he took Japanese culture seriously and tried to educate Westerners by adding descriptive captions below the photos. Instead of following western photographic conventions at the time, he tried to bring a Japanese aesthetic to his work. He like to photograph moments on the streets of Yokohama and arrange them in his studio when he could not (Luppino, 2009).

Beato’s studio inspired Japanese photographers to open their own studios, but the first native studios suffered from lack of resources and expertise. Shimooka Renjo (1823-1914) opened the first Japanese-operated studio in Yokohama. Uchida Kuichi (1845-1875) managed to attract the attention of Yokohama’s foreign residents but failed to get the interest of rich foreign travelers (Gartlan, 2006). However, Beato also employed many Japanese as assistants, giving them the training and connections they would need to succeed where other Japanese-owned studios failed. Beato hired ukiyo-e artists and colorists to paint photographs. In fact, Yokohama photography became associated with fine hand-colored photographs, painting details as fine as fingernails. These assistants became the pool that allowed Japanese photography to move away from foreign studios. Among these assistants arose Kusakabe Kimbei.

Kusakabe Kimbei, The Most Prolific Yokohama Photographer

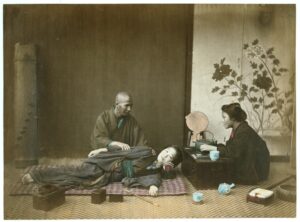

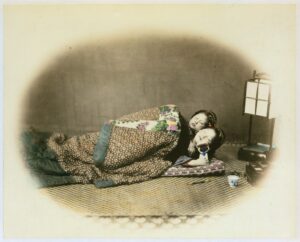

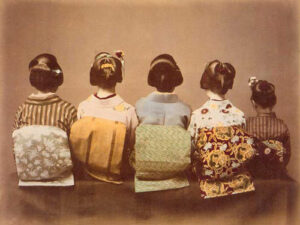

Kusakabe Kimbei (1841-1934) left his home in Kofu at the age of 15 or 16 to work at Beato’s studio. After 18 years of working with Beato, he set out to found is own studio in 1881 where he would produce 60% of surviving Yokohama photographs, making him the most prolific photographer of the time (Newton, 2008; Wakita, 2009). While Beato had respect for Japanese customs and tried to capture Japanese aesthetics, Kimbei used photography to capture the vanishing world of traditional Japan. At the time, women across all social classes were adopting Western hair styles and dress. Kimbei preferred to photograph tradition fashion, and he resisted Western introduced poses, such as women holding interlocked hands and other romanticized poses (Wakita, 2009). Instead, Kimbei embraced the bijinga, or pictures of beautiful women, tradition in ukiyo-e and adapted the woodblock print’s compositions.

He primarily hired geisha to pose for him for several reasons. First, social class mattered, and ordinary women wouldn’t pose because of their awareness of their class and of the wide audience the photographs would reach. Geisha were more comfortable with this because of their social status and because of their profession’s visibility. They also didn’t subscribe as readily to the concerns surrounding photography during its early years. Some people thought photography would steal the model’s life-blood, or cause a man’s shadow to weaken–I’m not sure exactly why this is a concern. Some thought every third person sitting in a photograph would die or suffer a shortened life span for each sitting they did (Wakita, 2009).

Because of this, Kimbei resorted to using just a few famous geisha. In fact, we even know their names: O-en, Ponta, Momoko, Tsumako, Azuma. and Miyako. However, this association of geisha and photography led to the public viewing geisha photographs as erotic works. A story in Tokyo shin hanjoki talks about the embarrassment of young boys who were teased by other people as they tried to buy photographs of geisha (Wakita, 2009). Despite this, bijinga photos became popular. He often depicted women painting, reading, and playing instruments– the same type of scenes found in ukiyo-e. Women appeared as cultivated and traditional.

The Importance of Yokohama Photographs

Beato and Kimbei’s work, in particular, defined the period and how people thought of Japan at the time. They provided a window for the West to look into. At the time, Japan was an exotic place few knew anything about. While the Yokohama photographs catered to this audience, they also showed a country in a state of change. Old customs fell away as new, western ideas entered and mingled with tradition. Admittedly, some photographers of this period created works that would later be used to fuel the racial profiling and ranking by those in the West. On the whole. Yokohama’s wonderful hand-colored photos introduced a level of artistry that changed how people in the West considered photography.

Yokohama’s photographs helped lay the foundation for the export of anime and manga and other Japanese media. They introduced a sliver of Japanese culture that allowed people in the West to become familiar with the culture, even if at a superficial level. Over time, Japanese aesthetics, with a little Western convention to make them comfortable, became accepted. It wasn’t such a big deal to see people in kimono. This gradual trend sped up after World War II when the United States had more direct contact with Japanese culture during the occupation. However, Yokohama and the work of people like Lafcadio Hearn, who introduced the West to Japanese stories, laid the groundwork for the anime and manga we enjoy now. Yokohama photography marks the first time a Japanese-Western product was made and exported. Manga and anime are also Japanese-Western products. Yokohama photographs tell stories in their own way; again, as manga and anime does.

Whereas Yokohama photograph combines Western technology with Japanese aesthetics, anime and manga reverse this. Anime and manga pull Western aesthetics, particularly those of Walt Disney, and combine with them Japanese technology. Over time, this created its own confluence of Japanese and Western styles we simply call the anime or manga style.

Finally, behind the photographs are people. We know next to nothing about Kimbei’s geisha models, but we can see them. We know their names more than a century later. Yokohama photographs, although they were meant for tourists, provide a glimpse at the lives of people long gone. They provide a glimpse at their stories. While today we don’t think images are a big deal–they are everywhere, after all–at the time they were shocked, awed, interested, frightened, and inspired. They allowed people to save a memory or see something they would never otherwise see. The demand for Yokohama photos and their subject matter reveals the interest people in the West had for Japan. The uniqueness of Japanese culture captured the imagination of the time and catered to an interest in something “pure.” That is, untainted by industrialization and mercantilism. Yes, this was an idealization, even a fetishization, of Japanese culture, but it came from a genuine interest in learning how other people live. The reasons behind why a photograph was taken matters as much as the subject of the image.

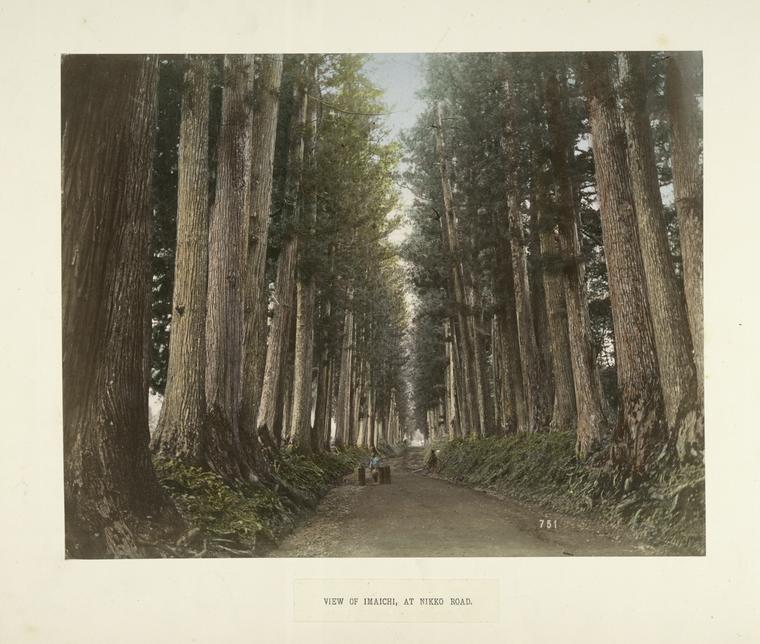

All of this aside, the Yokohama photos are simply beautiful. I’ve included a collection of them for you to enjoy.

References

Gartlan, Luke (2006) Types or Costumes? Reframing Early Yokohama Photographyt. Visual Resources 22 (3) 239-263.

Luppino, Tony (2009) Koshashin” A New Collection of Early Japanese Photography Captures a Moment of Change in 19th Century Japan. Arts of Asia 39 (3) 142-149.

Newton, G. (2008). Local heroes of early photography in Asia and the Pacific. Artonview, (53), 36-39.

Wakita, Mio (2009). Selling Japan: Kusakabe Kimbei’s Image of Japanese Women. History of Photography. 33 (2). 209-223.

Wilson, Michael (n.d.) Beato, Felice. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/41130

You can find most of these photographs at the New York Library Digital Collections, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection.

Photographs