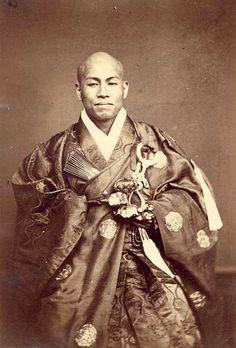

Photographs are everywhere. Every cell phone has a camera stuffed into it. Selfies and photos in general are so ubiquitous that they often lack impact. Even the most stunning photos make us shrug and click on to the next website. But if we stop and consider photos, they are a marvel. Photography captures a moment in time. The moment may be contrived, posed, or spur-of-the-moment, but it is still a glimpse at a time period. It is a glimpse at a person long gone.

Photographs are everywhere. Every cell phone has a camera stuffed into it. Selfies and photos in general are so ubiquitous that they often lack impact. Even the most stunning photos make us shrug and click on to the next website. But if we stop and consider photos, they are a marvel. Photography captures a moment in time. The moment may be contrived, posed, or spur-of-the-moment, but it is still a glimpse at a time period. It is a glimpse at a person long gone.

The number of photos floating around the Internet combines with our ever-onward rush to consume information. How often do you stop to contemplate a picture for more than a few seconds? I am guilty of rushing onward too.

Why is this woman wearing Western style clothing? What was her name? What was her favorite food? She was a predecessor to the moga of the 1920s. Moga is short for modan garu, or modern girl. She was a hip, liberated woman for her time. Moga typically wore one-piece dresses that ended at the knee, high-heels, and sheer stockings. A hat made of soft fabric accented her short hair styled after popular American film stars (Sato, 1993). Our lady has the hat, but her dress looks Victorian. We can only speculate about how she viewed herself. Many of these photographs are for postcards meant to be sold in the West. But they are still glimpses of people and periods lost to time.

We can’t forget the people not seen in these photographs: the photographers. The names of photographers are sometimes as mysterious as the people depicted. What made the photographer set up this shot? What relationship did the photographer share with the people in the picture? We can rarely answer these questions.

These people are gone. These frozen moments tantalize. The toy cat on the right side of the photograph and the thick blankets surrounding the child speak of the mother’s love. The ink paintings in the background are lovely. What do they tell us about the family?

We happen to know who took these hand-colored photographs. Felix Beato, an Englishman, used glass plate negatives coated with egg whites. This technique allowed photographers to capture detail but at the cost of long exposures. It took 4 hours to make a photo. However, Beato figured out a way to reduce the exposure time to 4 seconds. He took photographs in Egypt, China, and many other locations. He lived in Yokohama (Nobuo, 1972).

We rush about both online and offline by our societies. We bounce to and fro, forgetting how to look deeply. Look at these photographs for several minutes. Look into the eyes of these people. Perhaps someday someone will look at photographs of you with the same questions you have. Who is this? What was their favorite food? Favorite color? What were they thinking? Why was the photograph taken?

Or perhaps they will only spend a few seconds glancing into your eyes before moving on without thinking of these questions.

We live in an exciting time. A few clicks pulls up hundreds of frozen memories, but appreciation for this remains low. It’s human nature to grow accustomed to the everyday. It takes effort to cultivate thankfulness and mindfulness. These photos of people long gone reach across time if we stop and listen. I find this exciting and humbling. Even contrived postcards offer a glimpse of a different era and way of thinking. Japan was opening to the world after a long period of isolation under the Tokugawa. These photos suggest anxiety and excitement, a curiosity for the new, and a desire to reach out to the West. For the Japanese at the time, the West was just as alien as Japan was to the West.

References

Nobuo, I. (1972). BEATO IN JAPAN. Image, 15(3), 10-11.

Sato, B. (1993). The Moga Sensation: Perceptions of the Modan Garu in Japanese Intellectual Circles During the 1920s. Gender & History, 5 (3). 363-381.

This is great, I love the style of those days

Yes, I enjoy the look of hand-tinted photographs. If only the style would return!