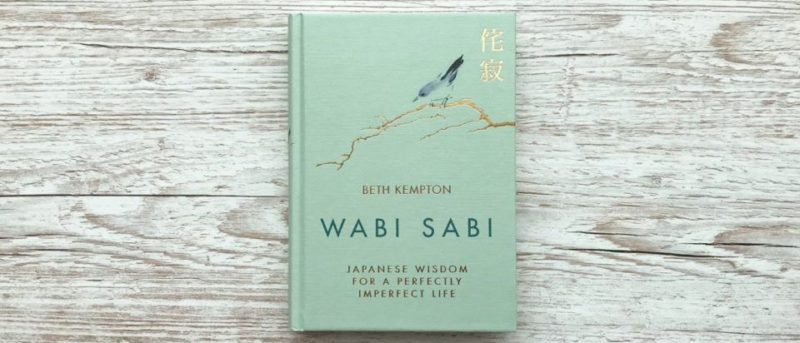

Kempton visits the origin of wabi sabi, defining each word and tracing its connections with tea. Four components make up wabi sabi: tranquility, harmony, beauty, and imperfection. Kempton stresses that imperfection doesn’t mean lower standards. Rather, it means you accept yourself as perfectly imperfect. A wabi sabi life is one of striving to do your best, but also not hurting yourself to achieve that goal. It means you are always striving but never straining. You need to be flexible and slow down to enjoy life.

After laying out these ideas, Kempton spends the rest of the book applying them to various situations. She begins with how to simplify the home. In this chapter, she explains how something can appear wabi sabi, such as a teacup or a rusted bucket but still not be wabi sabi. Remember, it’s a state of mind, of perspective. For example, I’ve seen some heralded wabi-sabi teaware and found it ugly instead of beautiful. It looked overworked, as if the potter was trying too hard to make it imperfect. To me, such teaware isn’t wabi sabi. It doesn’t resonate beauty, harmony, tranquility, and imperfection. Kempton stresses that wabi sabi is a personal matter. Because it stresses slowing down and looking beneath the surface of things, each of us will have a different perspective. You won’t see the same details I do.

The only true “rule” Kempton discusses is simplicity. Wabi sabi shares the same attention to objects as minimalism. We should only possess the objects that we use and find beautiful. Everything else needs to go. I’m a fairly minimal person by nature, but as I read the book, I wondered if I could pare down more. I own quite a few things that I don’t really use. Some are decorative, such as several books I own from the early 1900s. But at the same time, my house could quickly become too spartan, too empty. Kempton offers a quote from one of her teachers about this: “Spaces are ultimate created to be lived in and used, and if they don’t do that well, they are not considered successful.” So a space has to be inviting in order to be used.

Kempton goes on to advocate forest bathing–taking walks in wooded areas. She also discusses how we should bring nature inside our homes. Perhaps the most challenging chapter for people is about letting go and accepting our imperfections. Wabi sabi requires us to accept the past as past and let it go, while still learning from it. Something about modern culture prevents us from truly letting go. After all, we can keep exes and people we never see on our social media accounts. We have a misguided belief that we can control everything, fix everything, be everything. And that belief makes us carry around a heavy burden of memories that never heal over because we keep picking at them. We can’t accept the past as past. Many of us deal with anxiety, panic attacks, and other problems because we can’t accept and let go. According to Kempton:

Acceptance means saying:

- This is what is happening (observe it, don’t resist it).

- This is how much it really matters (if at all).

- This is the beginning of all that is to come, and this is what I am going to do next.

Basically, acceptance is acknowledging: this is where I am right now. She ties the chapter with the next one about reframing failure. She discusses how we should focus on the process instead of the outcomes of those processes. We should pursue excellence instead of success because we are never satisfied with any success we reach. Embracing the process allows us to not focus on perfection. Instead, we focus on learning from our inherent imperfection.

Kempton spends the rest of the book examining relationships, careers, and learning how to cherish moments. Throughout each of these chapters she offers exercises and steps on how to shift your thinking toward a wabi sabi perspective.

I enjoyed the book and came across several ideas I hadn’t considered before. It also reminded me that I need to work on my own practices. With all the busyness that surrounds me and the extra busyness I bolt onto my schedule, I need reminders to slow down. Slowing down is hard for me. In fact, relaxing to an afternoon of movies or just walking without a goal feels like more work than work. Kempton’s book showed me that I need to watch my workaholic tendencies more closely. It’s fine to enjoy writing and all my other hobbies, but I also need to find space to just be.

If you are interested in learning more about wabi sabi and how to start cultivating simplicity, harmony, and the like, I recommend you give this book a read. It’s a relatively short read. I wish she would’ve delved deeper into Japanese history, particularly on the four concepts of beauty. I would’ve enjoyed that more than her personal anecdotes. But I still enjoyed the book. If you are interested in an overview of Japanese wisdom centered on perfect imperfection, be sure to give this one a read.