Journals help with mental health, self-development, and, for the purposes of this essay, understanding history. Few people start a journal with the belief that mundane, daily concerns will prove to be a historical treasure. After all, who wants to read about teen angst, small concerns, trifles, or anything else some stranger wrote? I’ve kept sketch journals since I was a teen, and I don’t want to revisit any of them! Yet, these journals, centuries later, reveal minds, customs, events, and literature that prove invaluable for understanding long-lost eras.

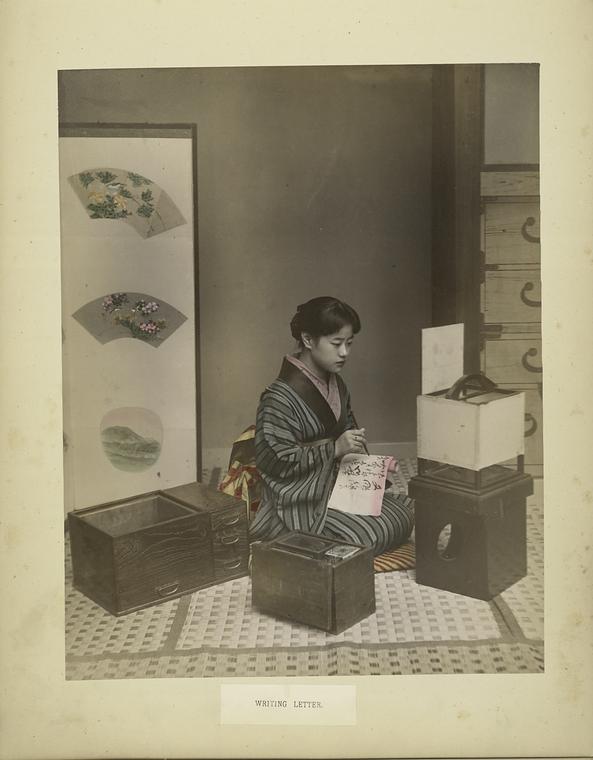

That’s the thing about the mundane: we take it for granted. But what is normal and mundane now will be exotic, confusing, misunderstood, or forgotten in the future. After all, what’s taken for granted typically isn’t recorded, except in personal journals. Precious few journals survive the passage of time because they are lost to weathering and decay, discarded by people, buried and never discovered, and a host of more reasons to discard than to keep. Because, again, who cares about great-great-great grandmother’s teen diary? Only some of the most valuable Japanese works of literature are journals of a sort: the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagen, The Diary of Lady Murasaki, and The Confessions of Lady Nijo. These journals were meant to be read by others, so they aren’t journals as we think of them, but they are journals in that they record the daily concerns and experiences of the women who wrote them. As any amateur history enthusiast knows, women’s voices rarely appear in the historical record, especially as candid as these journals offer.

Candor makes journals invaluable for history. Lady Nijo’s journal provides a look at the dark side of the Japanese court and the role of women within that system, yet it also reveals the education opportunities she and other women had. We get glimpses of fashion from Sei Shonagen, and, while not a journal, the letters between Hideyoshi and his wife Kitanomandokoro, provide an interesting side of Hideyoshi, who many historians usually show as singularly bloodthirsty. In her journal, Lady Murasaki shows how she didn’t care for Shonagen. All of these details give us not only a glimpse at the people behind history, but also the details of how they lived.

It’s easy for forget that history isn’t about dates or facts or events. History focuses on people and their stories. After all, those stories and personalities shape events that we call history. Sadly, the majority of people disappear from our awareness, yet their work enabled the names we know, such as Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Takeda Shingen, and other so-called movers of history. It it wasn’t for the forgotten masses who enacted their policies and plans, the movers of history wouldn’t have moved anything. While for most of history, the common people left no written record, few educated people in history left records. Any surviving journal or fragment can provide a glimpse at something people took for granted and so fail to appear in the official histories.

In our age, the majority of people can write and read–skills once limited to only certain classes of people. Of course, during the Edo period, Japan had one of the highest literacy rates in the world, yet even there we don’t have as much literature as you’d think. How much of our digital information will survive? While we believe the Internet is forever, paper and clay and stone have proven longevity. Under the right conditions, paper can last centuries; whereas, our digital world only lasts as long as electricity flows and file types remain readable. Just how many file types are unreadable already? How much more will be unreadable in 100 years? And 100 years isn’t that long of time. So, all of this is a long-winded way to say, paper journals are superior to digital journals for future historical research. I won’t rule out digital content, but digital is so easy to produce, and we produce so much of it in every moment, historians will struggle to find what represents our true daily way of life. However, written journals take more effort to create than digital, so they are more likely to contain important, or at least contain less ephemeral information.

How do I Start a Journal?

There’s many systems for journaling, including the currently (previously?) popular bullet journaling. But you don’t need a system or anything unless you want to use your journal as a reference. Frankly, if you want to use a journal as a reference source, digital is your better option because it is more immediate in search capability. Journaling is about slowing down and listening to yourself and thinking deeply about a topic. Journals also contain your personal narrative. You don’t need a system. You just need a collection of paper and a pen and a flow of thoughts.

I prefer using sketchbooks for my journals. Leonardo da Vinci inspired me with his random pages of sketches, diagrams, stories, shopping lists, to-do-lists, and diary entries. You may prefer something with lines, however. Lately, I sketch less in these journals, but I like having the option. As for the sketchbook’s size, it can be anything you want. Then all you need is a good pen; it can be anything you like so long as it doesn’t smear. Pencil doesn’t work because it can smudge and disappear.

What do I Write About?

Everything and anything that you are thinking about! My journals contain snippets of philosophy I’m thinking about, quotes, sections of books with my thoughts about them, questions, story ideas, study drawings, landscape sketches, blog ideas, entire sections copied from the Bible and other books, and diary entries. A journal should be an uncensored area for you to dig into yourself and your interests and your thoughts. For a journal to be helpful, however, it shouldn’t be a place for complaining or wallowing. This reinforces thoughts that aren’t helpful. It’s more useful to take a hard look at what you are doing to cause your difficulty and what you can do to ease it. I suggest asking yourself these questions and writing your answers:

- What aspects of this situation are beyond my control?

- What aspects of this situation are within my control? (hint: your thoughts, actions, and emotions)

- Am I focusing too much on what is beyond my control?

- What can I do to change my role in the situation?

I find these questions helpful for difficulties I have. Sometimes the answer, as hard as it can be to accept, is to do nothing. Often no-action is the best action to take, especially when the majority of a situation’s factors sit beyond your control.

How Frequently Should I Write?

Many journaling systems suggest writing daily, but that can become a chore–just one more thing to do. You should want to write in your journal because it is an inviting safe space and not a daily task. I tend to write in my journal most days, but I also have long periods where I write nothing. It depends on how much thinking I need to do and what else is going on. Paper is the most patient of listeners. It will wait for when you are ready and wait for you to work out what you want to say to it. So, when you start a journal, keep this in mind. Use it as you feel you need to use it. The only wrong way to write a journal is a way that doesn’t help you or in a way that feels like a burden.

While your journal likely won’t be a historical find like Lady Nijo, Lady Murosaki, or Sei Shonagon’s writings, you never know! But you also shouldn’t let that stop you from being free and uncensored in your work, unless you plan to allow others to read them as these three women did (although Lady Nijo’s journal doesn’t appear to be aimed a public readership). Journals, however, can help or hurt you. If you use your journal to wallow in self-pity or reinforce destructive thinking, you’re better off not journaling. Instead, use your journal to assess yourself and delve into your interests and the reasons behind your habits. Use your journal to make sense of how you make sense. Just don’t make your journal a job. Your journal should be a friend who listens when you need her. And don’t forget to jot down the mundane. You will soon find the mundane parts of life aren’t so mundane. And, in the process, you might give some far future historian valuable insight into our age.

I think there’s some room for complaining to a certain degree while journaling. Especially for men who struggle to name their emotions/feelings. While I don’t complain much if I do journal, I do make notes about how much I’m at my limit about certain things.

Journaling has helped me a few times when I needed to process things, so yeah, I’m all up for it.

Some complaining is fine. It’s just a bit too easy to fall into filling a page with nothing more than complaints, which isn’t helpful for changing your mode of thinking. I’m guilty of filling a page with complaints and rarely feel better for it!