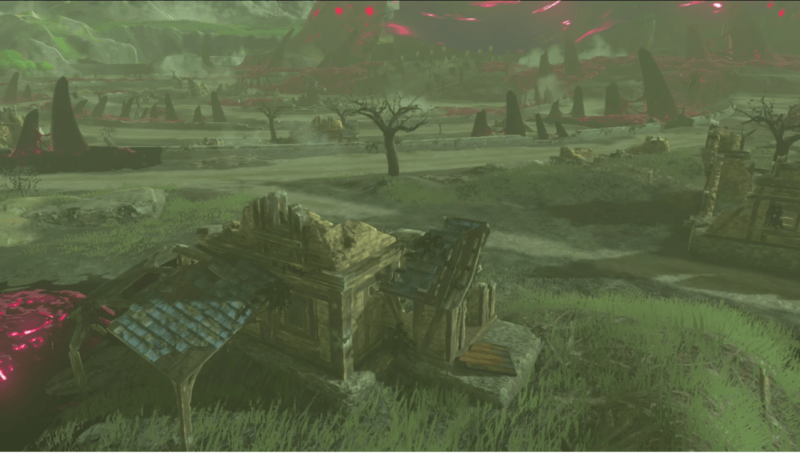

Many people criticized The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild for its lack of storytelling. As I revisit the game, I struggle to understand their viewpoints. After all, Breath of the Wild features more storytelling than any other entry in the series. But all of it is subtle. For example, when I wandered into the Hyrule Garrison on Hyrule Field, I saw the remains of a Guardian surrounded by rusted weapons. The Guardian had cut a trench into the earth, finally stopping against the remains of the wall. In the game, Guardians can only be killed by Sheikah weapons. The fact you see so many Guardians brought down by standard weapons reveals how hard the soldiers of Hyrule died.

According to the game’s story, after Hyrule Castle’s town burned, the remaining soldiers ushered the surviving civilians south to Hatano. They led the Guardians north where they took a final stand at Akkala’s fortress. When you visit the fortress, you find other Guardians with weapons thrust into them. The soldiers died hard, knowing they were distracting at least some of the Guardians from the civilians, their families, to the south. Likewise at Hatano, where Link fights until mortally wounded, you see the common soldiers destroying Guardians on the walls–the final defense against the slaughter of the families. If you look closely, you can see how fights between squads of soldiers and Guardians progressed in the ruins.

How is this a lack of storytelling?

Throughout your exploration of the ruined Hyrule you come across shrines and ruins that hint of stories. The shrines Link encounters house sokushinbutsu, whose stories I already written about. Ruins throughout the land speak of lives lost. The Shadow Hamlet on the cliffs of the Eldin region shows signs of a lava flow forcing people to flee. You see burned out villages that once would’ve been trade hubs because of their locations. And then there’s Link’s story. We don’t know much about Link, other than his father was also a soldier. But consider how he wakes 100 years later after being mortally wounded. Nearly everyone he knows has died. They died in by being incinerated or of old age. Many of the soldiers who fought the Guardians would’ve known Link. They would’ve been his friends and comrades in arms.

All of them dead.

We can assume Link’s father would’ve fought at Akkala if he was still alive, considering the legacy of the hero. Although we can only recover a few select memories in the game, Hyrule’s destruction would’ve held more for Link. The subtle music themes you hear among the silence of the wilds suggests what was lost. What Link had lost. You also have the mysteries of the land itself, such as what burned a hole through Hebra Mountain.

The criticisms toward Breath of the Wild’s storytelling reflects more on the reviewers than the game. People miss subtle storytelling; most of us have gotten used to–what I frankly find insulting–spoon-fed stories. Stories bludgeon us with themes. I’ve been trying to watch The Handmaid’s Tale. Beyond my frustration with the protagonist’s passivity, the dystopia has a cartoon feeling to it. It is too overt to take seriously. A more subtle approach would’ve been more engaging and terrifying. But our media doesn’t allow for subtly. If you watch old horror films, they leave most of the horror to your imagination. Watch The Body Snatcher with Boris Karloff for a good example. But today’s horror films have to show every act of violence and drop of blood. The end result is less horrifying and rather insulting. It prevents the viewers from being as engaged as old horror films.

Good anime hints at relationship factors not shown on screen. After all, we only see a portion of the character’s lives. We Never Learn, for example, suggests a lot more than it shows. Nariyuki has the responsibilities of being an elder brother. Sometimes the anime dedicates an episode to this, but it also hints at it as a part of his daily life. It leaves the viewers to piece together the rest. This engagement allows people to get into a story, to own it. Sure, the viewers’ conclusions will differ from each other and the author’s, but storytelling involves the ownership of the listener. When a writer shows too much, the reader (or player in the case of Zelda) loses the engagement. The writer talks down to the viewer, not trusting her to own the story in her own way.

Breath of the Wild trusts the player. That’s why it has the best storytelling of any Zelda so far. Certainly, the told story isn’t as cohesive as other Zelda games. But the subtle storytelling, the teasing of the player’s imagination, surpasses previous games. It doesn’t spoon-feed you. Instead, it has you discover ruins and leaves you to draw conclusions. I found this approach to storytelling refreshing, but I also felt disappointed that so many people failed to see it.

Yes! I wish more people felt this way. When you have this information, it just makes Link’s memories much sadder. Especially in the case of Princess Zelda. She was responsible to save all of Hyrule, but then you see the ruins and understand why she blames herself

Tears of the Kingdom builds on Breath of the Wild’s storytelling in the same way. Tears shows the story more directly, but there’s all sorts of details scattered around that underlines the events of Breath of the Wild. They are both well done.