Flashes of magical energy engulfed my cohealer, and an explosion rocked the top of the tower. The creature–a disembodied head and hands the size of a house–smacked the warrior holding her in place. I raced to heal his wounds and my own just as another explosion hit us. Where was the other team? I glanced around to see the other two teams of eight people were dead. Without my cohealer, my magic was strained, and two of my party members hit the dirt. My remaining companions, knowing I had to keep myself and the warrior alive, did what they could to not strain my dwindling strength. They also knew that they had to fill our limit break energy before my magic expired if we were to have the chance to live through this battle.

Explosions continued to shake the tower.

My magic strength gave out. In desperation, I downed the last potion I had and used a final skill to boost me in the short term in exchange for a long-term negative effect. I had no other choice.

But the creature’s damage output was designed for 24 people to share. Not a remaining party of five.

My magic strength gave out again. My warrior noticed and activated his Hail Mary skill to give himself another 30 seconds to live. We both know when he goes down, I would be next. But the damage dealers had managed to fill our limit break reserve. I squeezed out one last heal and dashed toward the center of the battlefield to give myself a few more moments of life when the warrior drops.

With a swing, the creature breached my warrior’s final defense. He went down.

The creature turned toward me.

I channeled the limit break energy. Wings sprouted from my shoulder blades, and energy surged through me. I touched the ground, feeling the energy dash from me and toward my fallen teammates, flooding them with life. The creature swung for my head.

I went down.

The newly revived warrior and teammates attacked and burned down the creature, clearing the dungeon.

Back when I played Final Fantasy 14, I had many experiences like this as a healer. The rush of saving a dungeon run from defeat pumps the same dopamine real-life experiences cause. The comradery of the moment, the teamwork, gives you warm feelings.

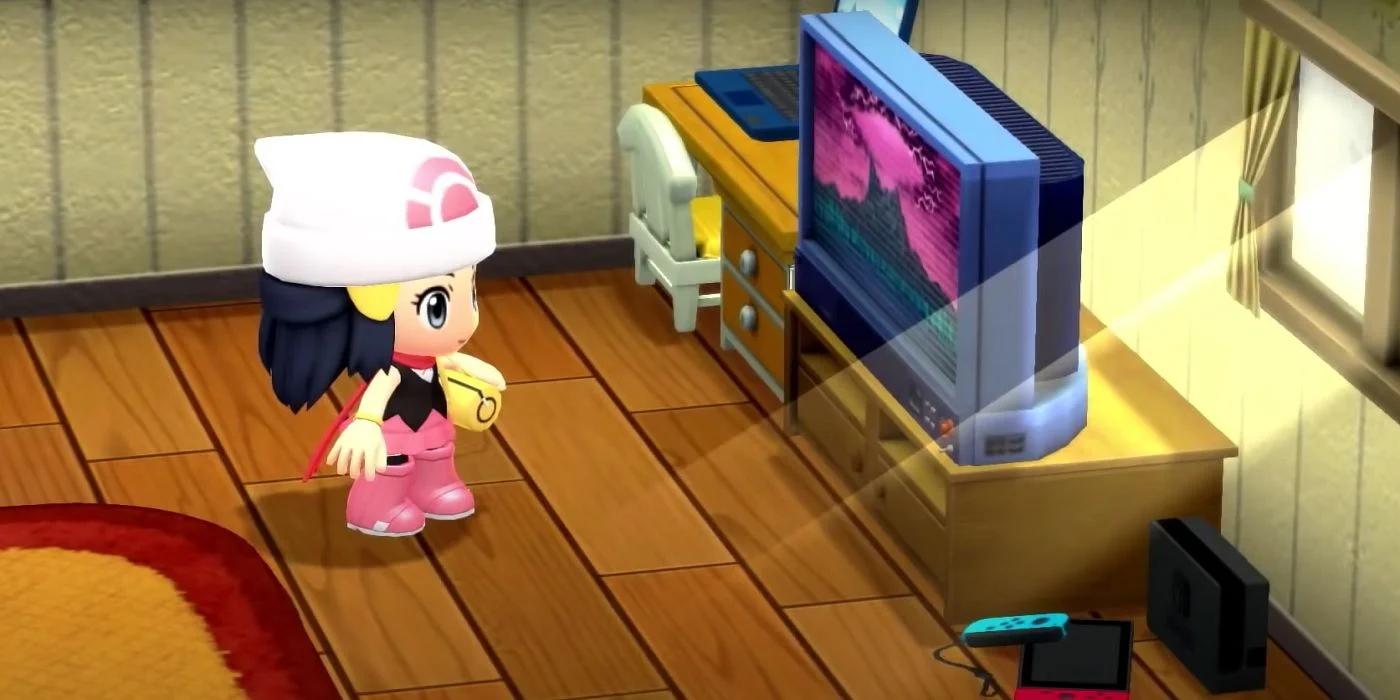

I spent many, many hours playing video games. Sometimes, I feel guilty about all this time spent gaming. After all, these hours are gone and I have little to show for them. I didn’t learn any skills that carry over to anything outside of playing video games. However, I usually played games instead of watching movies and television. Yet I also came away with memories and ways of thinking from the games I’ve played. I’ve written about how The Legend of Zelda has influenced me. But how do such experiences compare to real life?

I’m not the athletic type. In fact, I view competition as immature, especially if it is driven only by the desire to win. So I’ve never had anything close to the experiences I’ve had on video games. That rush. That elation. The raised heart rates as adrenaline activates. And the brain doesn’t distinguish between the virtual and the real. For the brain, an experience is an experience. It goes by sensory input, which opens the mind to manipulation by video games and virtual reality (Madary & Metzinger, 2016). So the experience I had on Final Fantasy 14 might as well had happened in reality. In fact, the memory remains vivid despite how it happened several years ago. I have other video games memories like that. They stand out against the backdrop of everyday life.

Of course, I also have memories of real-life adventures, but they don’t hit the same level of adrenaline or elation as what video games achieve. After all, video games are engineered to manipulate us in that way. The combination makes video game experiences addictive. You can be something that is impossible to be in reality. In the end, the experiences you have are real even if they are virtual because of the memories they leave and the way our brains react to them. With online games, we are interacting with real life people, even if it is through a screen. And those interactions are real.

Instead of asking if the interactions are real, we should ask if we are focusing too much on them. I spent too much time playing games in the past. It prevented me from writing, reading, creating art, and other aspects of living in “meat” space. After all, that is where we live. We don’t live in video games or in virtual reality systems. Even when they become more sophisticated, we will remain in our bodies. All of this sounds obvious, but our lives are increasingly moving online. The boundaries blur.

But online living, living in video games, doesn’t create contentment. Studies have found heavy social media users have more depression, and it isn’t a case of the depressed using social media more. Rather, social media seems to cause depression, especially in children and teens (Wakefield, 2018). Video games share many of the same similarities as social media. So it stands to reason that they can also cause depression if misused.

I still play video games, but I limit them to just a few hours a week. The rest of the time, I read, write, draw, and otherwise be present in reality. Video games give you real experiences just as books and movies can, but they can’t replace reality. I consider video games superior to passively watching movies and television because they require thinking (depending on the game you play, of course). Video games can sharpen your thinking and, depending on the game, make your more patient and less impulsive. Our minds are formed by our experiences and the stories we consume, no matter where those experiences and stories come from. Video game experiences are real and do impact us. Be careful of what video game experiences you choose.

References

Madary, Michael & Metzinger, Thomas (2016). Real Virtuality: A Code of Ethical Conduct. Recommendations for Good Scientific Practice and Consumers of VR-Technology. Robot. AI. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2016.00003

Wakefield, Jane (2018) Is social media causing childhood depression? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-42705881

An interesting train of thought.

I guess in terms of multiplayer games, there is a “realness” to your interactions with each other and the relationships you build, although at the same time, compared to a “meat world” experience, there are never going to be as many choices around how to react, and the motivations for acting certain ways will be different too. As the most obvious example, how many people would endanger themselves for the sake of helping others?

I guess rather than it being a black and white real or fake experience, maybe there’s something of a spectrum there and it depends on what we take from it as an individual.

At the same time though, I completely agree with everything you’re saying and I don’t want to romanticise the idea of gaming against the benefits of moderation and seeking real experiences.

PS: I love FFXIV!

I agree with you about the spectrum idea. Few elements are truly binary despite how often we think in binary ways.

Gaming experiences can reinforce our temperaments and habits. After all, gaming is an action, and all actions, whether we are aware of it or not, influence us. Perhaps tanks and healers are a little more likely to endanger themselves to help others ;).

Despite having a physical, “sensation-seeking” personality and not playing video games at all, I spent a great deal of time in college (80s/90s) sitting in front of various computer terminals, hyper-focused on programming mathematical simulations in either Fortran or an assembler. The dopamine experience of getting something to work was perhaps less spontaneous than playing a video-game, but likely no less intense and certainly no less real. The human brain is wired to elicit pleasure, or at least satisfaction, in finding and using patterns. With regard to what we feel in the moment, where the patterns originate seems less significant than that they’re discerned and exploited.

The fact the brain doesn’t care what the inputs are can be both a strength and a weakness. It’s certainly an interesting trait.