Because speech emerges externally from internal activity, whenever you are restless you speak thoughtlessly. You’re apt to be garrulous and flippant, speaking immoderately, talking too much, perhaps making up tall tales for the occasion, perhaps angering others by intemperate words. -Yamaga Soko

Yamaga Soko (1622-1685) wrote many bits of wisdom to the samurai he knew. That wisdom remains relevant for us today. American society values talkativeness. As Susan Cain wrote in her book Quiet:

The U.S. is one of the most extroverted nations, according to studies, and our society is skewed toward favoring extroverts. Our culture, including schools, social institutions, and workplaces, celebrates and is shaped around an “extrovert bias”—a belief that the ideal personality type is someone who is highly sociable, self-assured, and enjoys the spotlight.

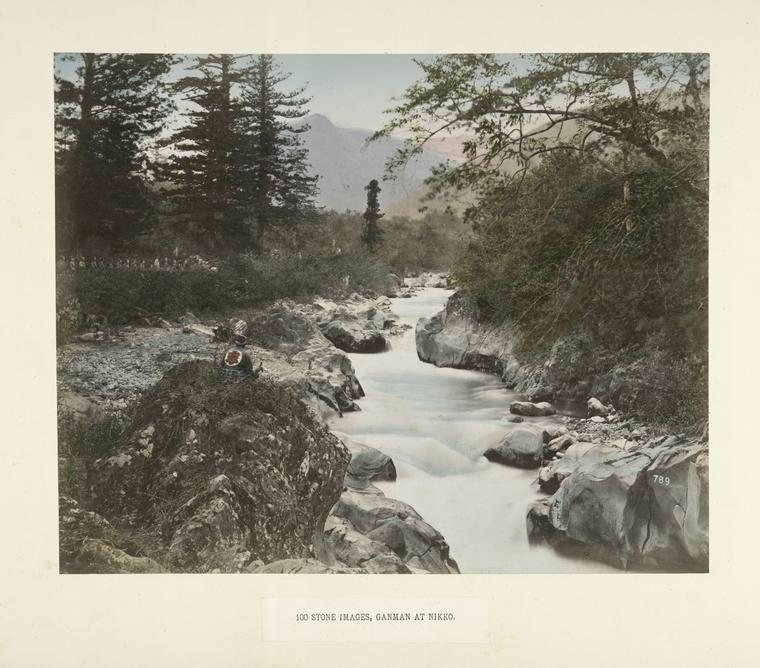

However, whenever you read literature in the past, Western or Eastern, quietude was consider a sign of character and of strength. Now, it’s a signal of weakness, indecision, and backwardness. The contrasts strike me. As a Japanese proverb states: “Numerous words show scanty wares.” I favor the ancients in this: silence is better. Yet, it is hard to practice in modern society despite how silence has been a virtue throughout Western history too. Somewhere along the way, the West lost this tradition, at least in the US. I’m uncertain when this happened. Zeno of Citium wrote during the Roman period:

The reason why we have two ears and only one mouth is that we may listen the more and talk the less.

And Epictetus, another philosopher of the Stoic tradition wrote:

Let silence be your general rule; or say only what is necessary and in few words.”

Fortunately, we have access to these and other writings, and Eastern writings offer another perspective on the art of calm silence. As Soko wrote in the quote above, speech is an external expression of internal activity. In Soko’s understanding, talking too much and talking thoughtlessly signals a restless, anxious, and unbalanced state of mind. Such a mind can lead you to tell “tall tales” or otherwise say something you will regret. Words once spoken can take on a life of their own. You lose control of words. People can interpret them beyond what you intended, fail to interpret them at all, or onlookers can mishear or misunderstand. When you don’t control your words from the start, speech becomes even more of a hazard for misunderstandings, anger, and other problems. Soko wasn’t the only writer who advocated for using few words and remaining calm.

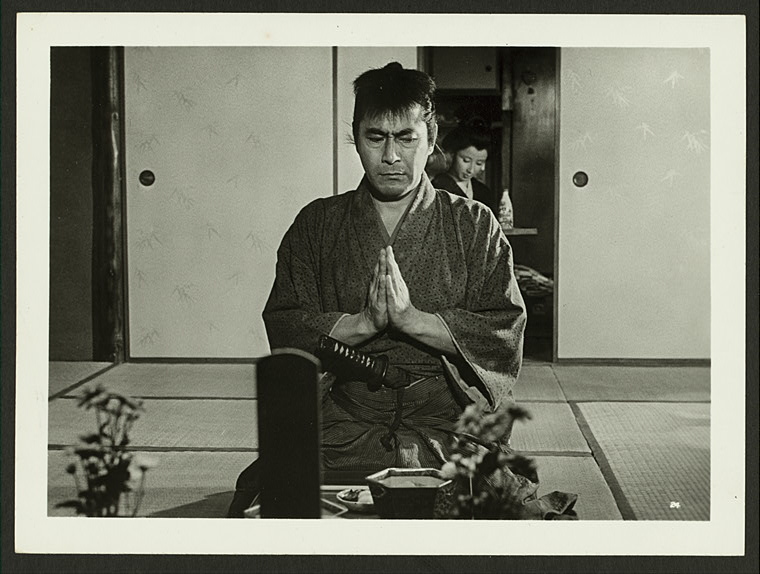

Even at one glance, the dignity of a person’s spiritual stature is apparent. There is dignity in humility and self-control. There is dignity in calm composure. There is dignity in speaking few words. –Yamamoto Tsunetomo

Tsunetomo basically echoes Soko: dignity is found in speaking little and remaining calm. The two can’t easily exist without each other. In order to speak little, you have to check–if you are American especially–your cultural inclination toward chatter. And to do this, you have to remain calm and in control. When you are frazzled, your mind lacks the resources needed to monitor your speech. When you have a habit of chatter, you default to that habit when your mind is rattled.

For example, I developed the habit of chatter long ago, of wearing a social mask, when working with the public. When I’m agitated or frustrated or otherwise lose my calm, I chatter to cover what I’m feeling and to put other people at ease. After all, silence unnerves people. Yet, this chatter comes at a price to my energy; it’s exhausting. And I’ve had my words gallop away, embellishing, speaking hyperbole, and otherwise speaking too much while saying too little.

To counter this, you have to practice calm. Learning to breathe and exist within the moment between an event and your response. You also ought to check yourself. When you want to say something, stop and ask yourself three things:

- Is it kind?

- Is it helpful?

- Is it necessary?

Of course, it’s hard to do this in the moment. But stopping to try this gives you a moment to take control of your internal state before you make it external. Once you make it external, there’s no taking it back. Fortunately, the majority of the time there’s no real or lasting problem with this, but sometimes the damage can be lasting and hard to fix. Words cut.

Silence isn’t an easy practice; practice is an apt word for it too. Even when you have a natural inclination toward it, quietude doesn’t come easily. It takes work to achieve the calmness needed to mind your words within the moment. Conversations should flow naturally, but chatter differs from conversation. Chatter falls into self-focused talk, as Soko pointed out. Chatter seeks to lift yourself in the eyes of others or otherwise cover insecurity or weakness or other troubled internal state. Silence, however, gives you a chance to step outside that internal state to focus on others. That’s why the three questions help. All three questions focus on the other. If it doesn’t benefit the other person, it’s best to remain silent.

Of course, this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t reach out for help if you truly need it. Chatter, however, may be a cry for help, but most people don’t hear it as such because they too are focused on their internal activity. Chatter can be a warning for yourself to pay attention to your internal activity–why you chatter. It could simply be a call for discipline and changing your habits, or your chatter may be a signal you need to seek better mental health. Philosophy offers some guidance. After all, many modern therapies developed from ancient philosophy.

In the end, the modern world needs more silence. While silence makes people uncomfortable at first–it forces people to stop making their internal states external without first paying attention–silence leads to a better life. Calmness reinforces silence and silence reinforces calmness. However, the practice isn’t easy. Silence takes time to learn, and achieving inner silence–the prerequisite for external silence–can be difficult. You have to learn to sit with your thoughts and listen to them without acting upon them. You need to study your patterns of thinking and learn how to direct your patterns toward your practice. And this takes many years of daily, even hourly, work. At least in my case it took about a decade of daily work before my mind quieted (for the most part). Now, I work to counter my public-worker habit of chatter. It helps to remember: your emotions; your responsibility. You are not responsible for what other people feel. This doesn’t give you leave to be callus. It gives you perspective on what you can control and what you cannot. You cannot control what others do, say, and think. You control what you do, say, and think.

Despite the effort, developing quietude improves your life. It also lends you an aura of dignity as a side bonus. You won’t be moved by the whims of marketing, politics, and other social pressures. Quietude doesn’t depend on external circumstances (although external things can make the practice harder). Quietude unlocks gratitude, appreciation for the reality of life, creativity, and a calmer life. But don’t be mistaken, it doesn’t come easily. Silence takes hard practice and internal house cleaning.

I should send this to my students because seriously a chance to breathe is a chance to talk and I really don’t think they can handle silence. Personally I think it’s the constant airpod use giving them all tinnitus.

Most people seem unable to handle silence. I know of many people who have to have some type of noise going at all hours.