“In all things, do not have preferences.” Miyamoto Musashi wrote this in his work Dokkodo: The Way to be Followed Alone. His work is a collection of practices he learned in his life.

The statement struck a chord in me. I’m an opinionated person despite my best efforts. I view my knowledge as an asset, which leads me to “teach” and otherwise have preferences about many topics. Most of my preferences are half-baked at best. Musashi’s idea to not have preferences extends to opinions and toward your own viewpoints.

We mistake preferences for reality, and we hold onto our preferences. After all, that is the nature of preference! We wouldn’t prefer them if we didn’t hold to them or like them. Musashi was Buddhist, and embraced the idea of nonattachment. Nonattachment is the idea that we shouldn’t hold tight to anything in life because everything in life is temporary. We hold preferences as close as objects. Perhaps even closer. Instead, Musashi suggests we shouldn’t hold those viewpoints and ideas. Rather, we should remain open to opposing views. Nonattachment extends to our thoughts. We ought not to favor our own thoughts and hold onto them as truth.

Whenever we feel defensive, we are holding onto a preference; we defend instead of listen. Agreeing with a view differs from listening. In reality, you are unlikely to convince people to change their minds, to let go of their preference. After all, how hard is it for you to let go of your own preference? People reason through their preferences just as the same as you do. Perhaps their reasoning is flawed, but it’s possible your own reasoning is flawed. By letting go of preferences, you can better adapt your thinking if your logic turns out to be flawed. Of course, this isn’t easy! A person without preference will listen and consider rather than hear and defend. This takes practice, and listening doesn’t mean you internalize the other person’s view.

One of the female warriors of the upper social classes in feudal Japan.

Marcus Aurelius, one of Rome’s best emperors, also advocated not having a preference in your perspective:

If someone is able to show me that what I think or do is not right, I will happily change, for I seek the truth, by which no one ever was truly harmed. Harmed is the person who continues in his self-deception and ignorance.

Not having a preference allows you to seek the truth and be mindful of your own thinking fallacies. Of course, it can also make you more subject to other’s whims if you want to please them. But pleasing people is a preference too!

Not having a preference allows you to exist in reality as it is. Here’s a small example: I was taking a roadtrip recently, and I prefer to listen to podcasts instead of music. However, I use Google Maps as my GPS and wasn’t going to play with my podcast app that day. I became frustrated, but then reminded myself not to have a preference. I allowed Pandora to play instead and ended up with a pleasant drive. While this is a trite example, we often allow small preferences spoil a day. Our work is more hectic than we’d prefer. You dropped a coffee cup and broke it. The store was out of bagels. When you don’t have preferences, you shrug and order a breakfast muffin instead. It avoids ruining your day.

I often have to remind myself to have no preferences when I begin to get upset with something. During my roadtrip, I got behind a slow-driving semi for many miles. The semi-driver was also inconsistent in speed. I would’ve preferred the driver to be consistent in speed or travel at the speed limit. I had to remind myself not to have this preference every so many miles. My irritation with the driver began to erode my enjoyment of the countryside. By reminding myself to avoid a speed preference, I could focus more on the slow-moving landscape.

Having no preference means you are flexible to meet the moment as it is instead of applying how you think it should be. This applies to people too, and I find this quite difficult. As a Christian and a reader of philosophy, I often think about how I and others should act in a given event. Reality and people rarely play out according to shoulds. Having no preference doesn’t mean you disregard your morality. It means you approach the moment without trying to enforce the shoulds. Morality guides your actions, and your actions are all you can control. The rest of the shoulds are out of your control and need to be beyond your preferences. Having a preference that doesn’t match reality hurts your ability to address that reality when needed. It can even hurt your ability to be a moral actor in a situation.

Musashi seems concerned about these shoulds in his writings:

You must understand that there is more than one path to the top of the mountain.

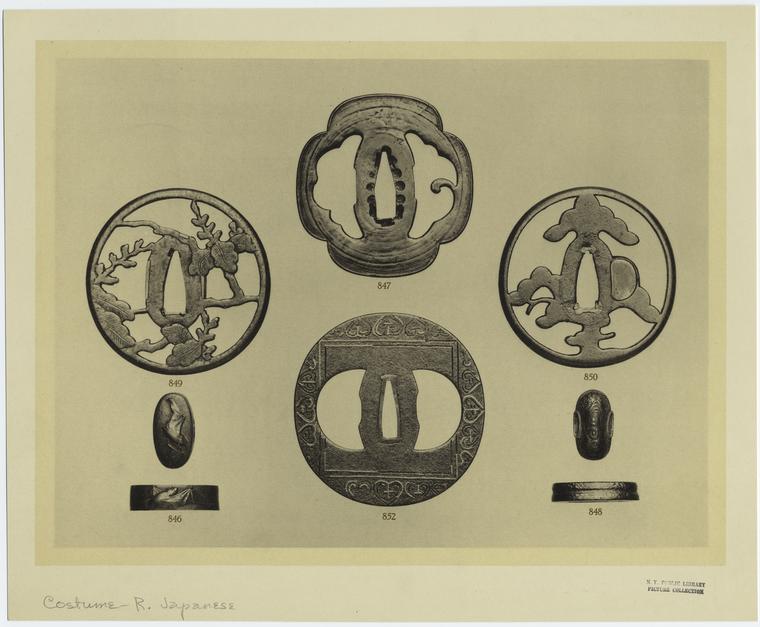

The primary thing when you take a sword in your hands is your intention to cut the enemy, whatever the means. Whenever you parry, hit, spring, strike or touch the enemy’s cutting sword, you must cut the enemy in the same movement. It is essential to attain this. If you think only of hitting, springing, striking or touching the enemy, you will not be able actually to cut him.

Musashi basically says you shouldn’t try to cut an enemy, or hit, or strike, or anything in a certain way. Rather, you should cut by whatever means needed instead of following a should-cut. He also explains how you need to be calm and considered in your approach to fighting and to life, to not be tense nor relaxed, to not be biased:

Both in fighting and in everyday life you should be determined though calm. Meet the situation without tenseness yet not recklessly, your spirit settled yet unbiased. Even when your spirit is calm do not let your body relax, and when your body is relaxed do not let your spirit slacken. Do not let your spirit be influenced by your body, or your body be influenced by your spirit.

“To not have a preference” means you need to be calm, flexible, and open to reality as it is. It means you avoid applying your shoulds to events. You can only control yourself. Reminding yourself not to have a preference helps you back away in the moment. It means you have the right to not have an opinion. Preferences can blind us to reality and to our logic fallacies. We end up acting upon what we think rather than upon reality. We act upon illusion instead of truth. Musashi phrases this idea in one more way:

Truth is not what you want it to be; it is what it is. And you must bend to its power or live a lie.