However, many younger countries go through a period of cultural rootlessness. By younger, I mean countries that developed later than the rest of civilization. The oldest civilizations include Persia (modern-day Iran), China, Egypt, Ethiopia, and similar nations. Now this isn’t to look down on Native American and other native cultures. They have the deepest roots of all. For my purposes, I’m focusing on nation states.

Japan is a relatively young nation compared to Persia, China, and even Rome. The Jomon period, dating around 1000 BCE, involved hunter gatherers that eventually formed tribes and kingdoms. Somewhere between the 4th and 9th century CE Japan coalesced into a nation state under the first Emperor. For perspective, the nation of Rome was founded perhaps in 753 BCE (or perhaps 814 BCE). That means Rome predates Japan by about 1,100 years. China’s earliest written records appear as early as 1250 BCE. The first dynasty of China begins at around 1600 BCE, 2,000 years before the first emperor of Japan. America was founded in 1776 CE. That’s 3,376 years after the first dynasty of China was founded and 2,529 years since Japan’s first emperor. Egyptian records date all the way back to 5000 BCE or 3400 years before the first dynasty of China. The States is a young upstart nation.

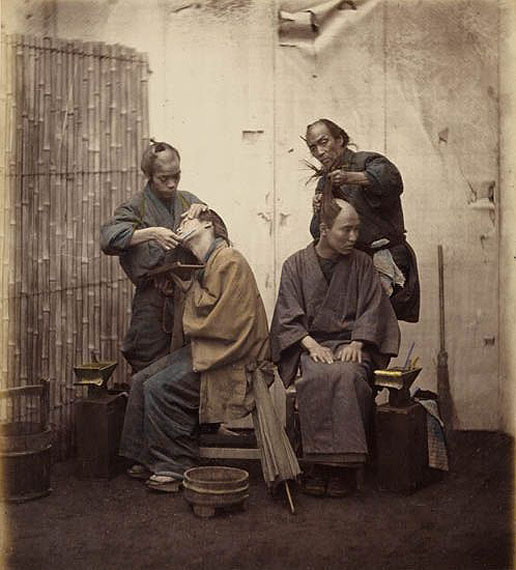

When Japan became a nation state, the aristocracy looked toward China as an example of what civilization meant. The Chineseness of Japan, if you will, reached its height during the Heian period where Confucian ideals, Chinese dress, Chinese writing, and other elements of Chinese culture became the norm. Japanese literature flowered with the influence–you see the Tale of Genji, the Nihongi, and other works of classic Japanese literature. The writers often seemed concerned about their relative newness as a culture and tried to insert Japan into Chinese history.

The sense of rootlessness happens whenever a culture feels disconnected from its history or when its history is too recent. Lack of community adds to this rootless feeling. The US deals with both of these factors. The nation is barely 250 years old, and our communities have fragmented because of our economic situation (encouraging mobility over rooting) and political situation. Ben Sasse, in his book Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal, sees three divisions in the US: the stuck, the rooted, and the nomadic. The stuck include people who can’t escape their situation because of economic and cultural headwinds. The rooted, the minority, are the foundation of a stable society. They form the communities and cultural framework. While the nomadic hop around the country chasing work and lack the feeling of community. The erosion of the rooted has shredded American’s societal framework and the shared belief in the American ideal: that all people are created equal and given by their Creator certain inalienable rights. Stuck people focus on survival and feel left out of the ideal. Survival situations often make people tribal. The nomadic are likewise too busy and too fragmented to engage in discussions based in the ideal. Only the rooted have the ability to come to civil disagreements. They know their neighbors well and have the stability to discuss issues without falling into tribalism. I suggest you read Sasse’s book if you want more details about this division.

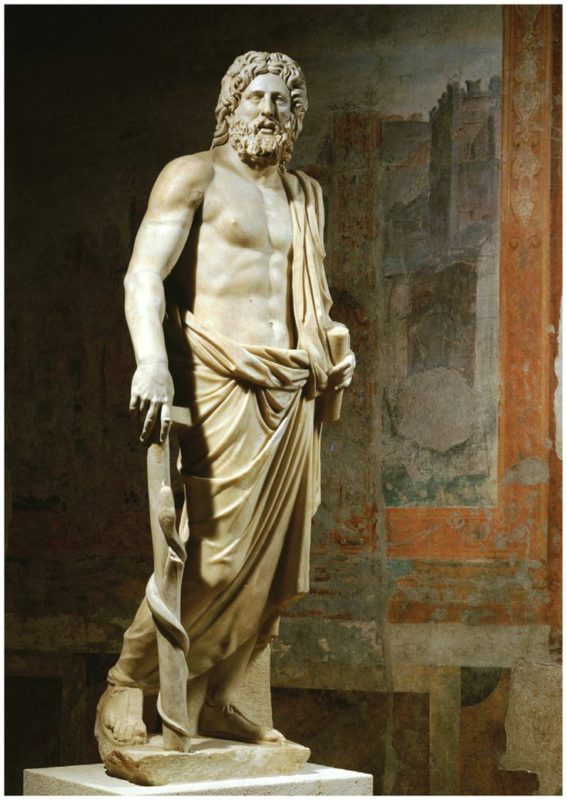

I feel drawn to cultures like Japan that have deep histories, but I cannot become Japanese. I can’t become Egyptian, Roman, British, or even Scottish despite being a Scotsman genetically. I grew up in American culture so any other culture I would adopt would be bolted onto that identity. Heian period writers may have emulated and absorbed Chinese culture, but they remained Japanese. When you compare the folktales from China and Japan that date from that period, you see a certain Japanese aesthetics despite the tales’ similarities. Whichever culture we happen to be born and grow up within forms the foundation for our perspectives. Even people I’ve met who grew up across two or even three cultures have a primary cultural perspective. Of course, that doesn’t mean we can’t adopt different views. My American perspective continues to change as I study Japanese culture, language, and perspectives. It continues to change as I dive deeper into the culture and language of the Roman Empire and early Christianity. But some aspects of my thinking, including the structure of my brain, remain a result of growing up as an English speaker and living in American culture. I feel rootlessness when I look at American culture as it is now, but I feel rooted when I see that culture as a continuation of the cultures that influenced it: Rome, France, Germany, England, Africa, and yes Japan and China. Studying history helps dispel rootlessness.

The US is going through the same growing pains Heian Japan went through. If you look at early American literature, you see an effort to create a sense of history, a mythology to provide a ground for a sense of American identity. The American identity sits on the American ideal and the effort to create a “more perfect union,” but people still feel a sense of disconnect. I see this with people who come to the library to work on their genealogy. They want to feel connected to their ancestors and want to visit their home countries in Europe. They want their ancestral soil under their fingernails. As a society, we can’t do anything about the US’s youth. All we can do, as Japan did, is look toward older countries for ideas and suggestions. Most of all, we have to lay a history that future generations can be proud to inherit.

I see where you are coming from in this post. However I dissagree on the rooting aspect you discuss. While it is fascinating to see countries with very long histories, at the same time they seem stuck at times unable to move on. (FYI- I have lived, worked, or traveled to 20 countries) I like the rootlessness being able to move, travel and appreciate things. Not being rooted has the advantage of being able to adapt and change more easily, and not continue things because that’s just the way things are.

Being rooted doesn’t mean you accept things just because that’s the way they are. Although I agree it ends up that way. Rootedness desires for the community to improve, which means the community needs to change. And that change requires people who are more rootless to bring in new ideas. But rootless people also need rooted communities in which to work and live. Both aspects are important for a society to develop a long history instead of stagnating and collapsing or failing to remain in place long enough to develop a rich culture.

It’s an interesting topic. I wonder how much of rootedness is related to the “age” of the culture and how much of it is just how common interaction with history is. I spent a good chunk of my childhood in Britany (France). We kids would meet up on Saturdays by the local chapel, which, while having been restored quite a few times over the centuries, originally dates back to the 12th century. It was just the most obvious point to congregate. Its steeple looms over quite a few of my childhood memories. The history that surrounded us went from the very old to the fairly recent, but it was all around us. We would play hide-and-seek among the 3,000-year-old megaliths in the nearby forest. I asked my first girlfriend to go out with me while we were sitting on top of a WWII German bunker at the beach. etc.

My experience of the US is that, generally speaking, history is separated from everyday life. It is often relegated to museums or sites that are explicitly meant to be “historical”. Meanwhile, the kids congregate at a mall. Or at a suburban park that was either previously entirely wild, or has been wiped clean from whatever historical markers were there before. In short, history just isn’t part of their everyday lives. As a result, that sense of connectedness with the past is only found by the minority of kids who express early on an interest in history, whereas in most of Europe that connectedness doesn’t require any effort at all: even for the least interested in history, it’s just there, as part of everyday life.

Sasse’s book sounds interesting and I’ve added it to my list of books to read. I’d note that the stress on communities caused by economic systems is nothing unique to the US. It’s a common concern in every country I’ve ever been to. The bulk of job opportunities is centred in a few select locations (Paris for France, Tokyo for Japan, etc.) and young adults often leave their communities for those locations, either to never return at all or to return only once they’ve reached a certain age. If they’ve managed to hold communities together better than in the US, it may be for other reasons (perhaps even just simple geography and access to cheap transportation. In France for instance it’s very easy, and fast, to go back and forth from Paris, so those who’ve “expatriated” there have an easier time maintaining contact with their community of origin, which is a bit more difficult in the US given the sheer distances involved.). One promising aspect of this pandemic is that it has proven that distance working is a viable option for many jobs (obviously not all, but many). It’ll be interesting to see whether this might increase the share of “rooted” people, since they would no longer be required to move in order to work the jobs they’re after.

Oh, and as an aside, I also wanted to react to this: “Even people I’ve met who grew up across two or even three cultures have a primary cultural perspective.” I think that varies widely depending on the actual experience of the person. For instance, some kids move around quite often, hopping from one country to the next as their parents get reassigned. Others move far less often. Things like that will significantly influence the cultural identity of the child. Personally, I’m at the intersection of 3 separate cultures. And I don’t think there’s any one of them that stands out as a “primary cultural perspective”. It’s more like clothes. I change them depending on the occasion. I think everyone does this (adapting their behavior and mindset to different contexts), but the extent of the variations is just more extreme when it’s across cultures.

Some people struggle with this. “But who are you really?” etc. I find this rather a shame. It implies that identity is monolithic, which it is not, or that there is some fundamental essence to it, which there isn’t. And it implies that adaptations of behavior are “fake”. Like if you behave one way with your in-laws, but another at work, and yet another at home, then only one of those is “really you” and the rest are lies. To me they’re all just facets of the same person, with none of them being more central to their identity than any of the others. That’s also how I relate to my own cultures. My primary cultural perspective is just whichever one is most suited to the context I’m in. Anyway, that’s just an aside but I wanted to throw in my own perspective on that.

You make a good point about how history is removed from American life. We have statues and cemeteries, but they tend to be limited to certain areas of the country. History in my area has few truly old landmarks. Most of them are graves. Of course, this is a little different toward the old colonies of the US.

The shift toward urban may slow with remote work. In fact, it could be a benefit by driving down the cost of living inside cities as the population pressure decreases. Both of which could increase rootedness.

You make a good point. It seems to be down to personalities. Thanks for sharing your perspective!