“Gokitaku hajimete desu ka?”

She wears white stockings and lace, a fantasy in the flesh. You nod and say something vaguely affirmative.

The server bows. Her petticoat and frilly pinafore are immaculate. You see just a hint of her garter. The other servers stop what they are doing and bow toward you.

“Okaerinasai-mase goshujin-sama!”

You have just entered a maid cafe.

Maid cafes are an example of a new type of business, called “affective economics.” Affective economics centers on inviting a customer into a brand community. This allows customers to become emotionally engaged with a brand or product and feel protective of that brand (Jenkins, 2006). Think about one of your favorite fictional characters and how emotionally attached you feel toward that character and story. That is affective economics at work.

Are you a sports fan? Does that loyalty drive you to buy stuff with the team logo? Does that loyalty make you want to watch every game? That is affective economics. It is rooted in a deep emotional attachment toward a brand that is supported by social networks. In other words, you like the stuff because people around you think it’s cool too.

Affective economics often involves payment for social ties. For example, you need to have a certain level of memorabilia to be considered a true fan in some social circles, someone who’s “in.” NFL fan communities and some anime fan communities share this. Maid cafes are all about this.

Maid cafes are built upon customer’s affective attachments toward the fictional characters the servers create. While the cafes sell food, photographs, and other products, customers mainly pay for the ability to interact with the maids. After all, that is why you are there right? This business model appeared in Akihabara in the late 1990s and early 2000s with the rise of otaku culture. The cafes simulated dating, uh, simulation games (they are a simulation of a simulation

). Each maid creates a fictional character she performs when interacting with customers. Customers also develop their own role playing identities (Hochiman, 2008; Galbraith, 2013).

- You cannot ask for a maids real name or personal information.

- No physical contact is permitted.

- No personal cameras.

- No sexual advances.

- You must order one drink.

Food offered a maid cafes are expensive. You don’t go to cafes to eat. You go to talk with the maids. Maids provide various services that center on the master-servant relationship maid cafes build. One common service is drawing a cute word or image on an order in ketchup. The maid will then ask the master, when she presents his order, to join her in an incantation to make the food taste better. The chants vary, but sources say the most common is “moe moe kyun.” Kyun is the Japanese onomatopoeia for a heart beat. Both maid and master make a heart shape with their hands over their hearts and moves their hands toward the food as if shooting a beam of heart energy. The idea is to infuse the food with love. It all contributes to the fantasy (D’Anastasio, 2013; Galbraith, 2013; Mounteer, 2014).

Each interaction costs extra. Cheki (or instant photographs of the customer with a maid (not touching, of course) are common at 500¥ each (Galbraith, 2013).

Maid Cafe Customers

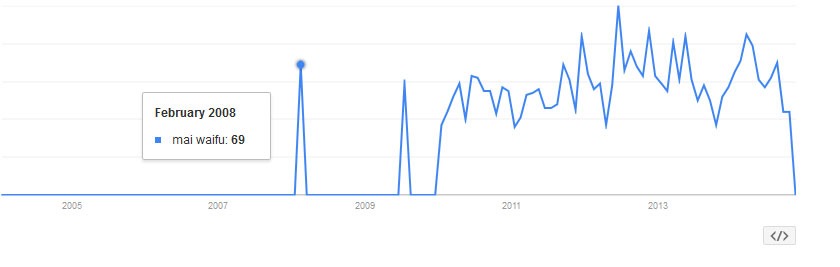

Maid cafes rely on regulars (joren じょれん) to keep the cafe going. Otaku of various flavors compose these regulars. The customers develop relationships with the maids. Well, they develop relationships with the maid’s fictional character rather than the maid herself. Maid cafes are considered 2.5 dimensional spaces (Gailbraith, 2013). They are places where socially awkward, withdrawn, or uninterested people can interact with a fictional character who is physically real. Waifuism deals with people marrying a 2D fictional character. Then you have the typical real world relationships of the 3D world. Maid cafes and similar venues sit between these two worlds. The maids are 3D, but they are fictional at the same time. This allows a person to interact with a fiction that is more palatable than the complex and stressful 3D world.

Maid cafe servers act cute and servile. She exists to please her master. She also adopts a completely different way of speaking and tone of voice in order to appear subservient and cute (Kawahara, n.d.). It is her job to create memorable, comforting, and fun experiences for customers. However, customers cannot be lewd or sexual in any way. Erections, lewd behavior, and other sexual or degrading behavior can cause the customer to be banned permanently from the cafe. Masters are expected to be masters of themselves (Galbraith, 2013).

Regulars only have one hour intervals like everyone else. Many will leave to only line up again. Japanese society often considers maid cafe regulars and other otaku as unmanly because they avoid fulfilling expected social roles and responsibilities, including having relationships with women (Galbraith, 2013). Men do not go to maid cafes in order to feel like a man. Rather, they go to relate with fictional characters in a cute, safe environment.

Maid Cafe Maids

Servers cannot help but develop some personal relationship with regular customers. After all, a server is still herself under the character. Regulars will celebrate their birthdays and other special events at the cafe. Many regulars visit for years. In such cases, it is impossible not to build some sort of relationship. After all, relations is the main product of a maid cafe. However, for her own safety she cannot give out personal or contact information (Galbraith, 2013; Levenstein, n.d.). Some customers will struggle to draw a line between fiction and reality.

Maid characters are inspired by manga and anime, but these characters are not specific renditions of popular characters. Rather, they are developed by the maid themselves (Galbraith, 2013). This gives the women a means of self-expression.

Maids are paid about 850 yen an hour at the time of Galbraith’s study (2013). This is close to Japan’s national minimum wage. Women are drawn to the work because of their interests and not the money.

Upon graduation, when she quits or is fired, a maid has a special event that includes a small circle of regular customers. Graduation marks the last time she will be seen in costume and character. Customers buy tickets to take part in the event, which varies by maid (Galbraith, 2013). The event is often emotional. It is a turning point and marks the end of the relationship between the maid’s character and customers. Basically, the event marks the death of that maid’s character.

Considering Sexism

At first glance, maid cafes look to be quite sexist. Men are masters (although women are considered mistresses and see the same attention as men) and the maids are servants. Maids act to attract men and meet their needs. That interaction is what the cafes sell. However, this does not necessarily mean there is sexism in the fantasy that is being sold.

First, most maid cafes have strict rules that seek to avoid sexual advances, lewd behavior, and other problems. Although, this suggests such behavior was a problem in the past. The outfits seem tailored for men’s fantasies. However, the maid outfits in most maid cafes are closely related to Lolita fashion. Lolita came out of a backlash against women feeling forced to dress in ways men favored. Female sexuality was expected to be accessible and match the taste of men. Lolita takes these expectations and embraces femininity to the extreme: lace and bows and other things considered feminine. Maid dress in the same way. Lolitas dress the way they do because they enjoy it. It is not done to please men (Steward, 2008). While maid costumes are designed to please the mostly male clientele of the cafes, the outfits are less demeaning than those of American establishments like Hooters. The outfits embrace and express femininity with lace, ruffles, and bows in ways similar to that of Lolita fashion.

Many customers are interested in playing around the boundary of fiction and reality. They go to maid cafes in order to relate to a character and enjoy an hour of escapism. Not all customers visit these cafes in order to feel like a master. There are other outlets for such needs, after all.

Links with History

Maid cafes are related to the famous Japanese tea houses and their geisha. Both the cafes and tea houses sell fantasy and relationships. Geisha and maids both converse with customers and provide a social link a customer may not have otherwise. Granted, maid cafes turned these interactions into commodities more than tea houses. Both geisha and maids are paid to provide social interaction, conversation, and other social needs. Affective economics focuses on how social and emotional ties are developed between people and products. Both geisha and maids sell a branded version of themselves that packages their time and interactions into a product. This seems a bit crass, but social realities are changing. Some people are attracted to fictional contexts, to use a technical term. In other words, people are drawn to fiction more than social reality. This context is related to, but different from reality. That is the attraction of both the Japanese tea house and the maid cafe.

References

D’Anastasio, C. (2013). Parfaits not perverts: inside NYC’s first ‘maid cafe’. Gothamist. http://gothamist.com/2013/11/11/she_just_took_my_empty.php

Galbraith,P. (2013): Maid cafés: The affect of fictional characters in Akihabara, Japan, Asian Anthropology, DOI: 10.1080/1683478X.2013.854882.

Hochiman, D. (2008) Service with a wink to a Japanase Fad. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/25/dining/25maid.html?_r=2&

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Kawahara, S. (n.d.) The phonetics of Japaense maid voice I: a preliminary study. Rutgers University. http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~phonetic/pdf/Kawahara-Onin16.pdf

Levenstein, S. (n.d.) Maid cafe code of conduct chastises creepy clients. http://inventorspot.com/articles/maid_cafe_code_conduct_chastises_creepy_clients_18430

Mounteer, J (2014). What it’s like inside a Japanese maid cafe. Matador Network. http://matadornetwork.com/abroad/like-inside-japanese-maid-cafe/

Steward, D (2008). In her Own Words. Jezebel. http://jezebel.com/5056920/in-her-own-words