What Exactly is Cosplay?

Cosplay involves more than donning a costume. After all, people don’t consider Halloween costumes a part of cosplay culture. We can define cosplay as a performance art. It involves more than dressing up. It involves people taking on the physical and mental role of a fictional character (Bainbridge, 2013). Cosplay expresses a fan’s adoration of a character. In a study of cosplayers, over 70% of people surveyed became fans of a specific character because the character possessed traits the fans wanted to have as well. The fans expressed a desire to “get inside the skin” of the character. Many of the fans surveyed (79%) stated they learned to draw by copying commercially produced drawings of their favorite characters (Rosenberg, n.d.; Manifold, 2009).

We call people who dress up like this cosplayers. The focus on the word play in both labels emphasizes two points: fun and performance. Cosplay involves 4 points (Winge, 2006; Bainbridge, 2013):

- Narrative – the personality and story of the fictional character

- Clothing – the design of the outfits and the community surrounding this design

- Play – mimicking the mannerisms of the character as accurately as possible

- Player – the character and identity of the cosplayer

Cosplayers identify wth the personality and story of their favorite characters, and this is the main drive behind cosplay (Rosenberg, n.d.). It’s fun to dress up as someone else! It helps when you admire that character, even if it’s just a cool outfit you like.

![By greyloch (Flickr: Superman) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://japanpowered.com/media/images//Smiling_Superman.jpg)

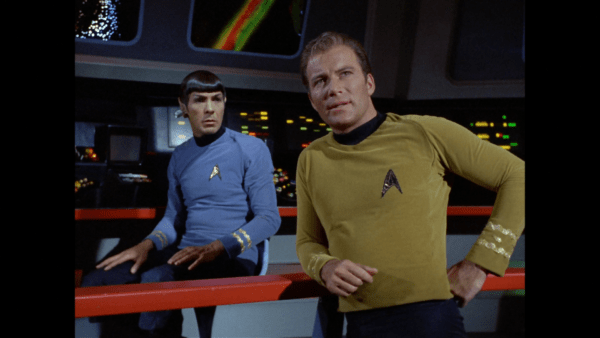

Authenticity can be difficult to achieve which the cosplay values it. Many character designs feature physics defying clothing. Especially busty female characters. Other characters sport details or designs that can be difficult to mimic, such as Samus Aran’s suit. This touches on an important point, cosplay doesn’t limit itself to anime and manga characters. It encompasses American superheroes, Star Wars characters, Star Trek characters, and video game characters. This hearkens back to the origins of cosplays as we shall see.

I have to note that Renaissance fairs and war reenactments are not considered cosplay. These costume events seek to recreate historical reality. Cosplay focuses on fiction, much like a Shakespearian play focuses on fictional characters (Caffrey, 2015).

Cosplay and Self Identity

Essentially, an anime or manga cosplayer can be almost anyone who expresses his or her fandom and passion for a character by dressing and acting similarly to that character (Winge, 2006).

The community aspect of cosplay matters. Making your own outfit ties the cosplayer together with the greater cosplay community. Competitions and donning the character’s mannerisms acts as a way to express yourself and fit into the community. It’s not unusual to see Bleach’s Ichigo square off in mock battles with Final Fantasy VII’s Cloud or other crossovers. These impromptu skits, when done well, earn praise from other cosplayers and create a sense of belonging. Shared interests cement people together. Who you chose to cosplay as–the word acts as both a noun and a verb–creates a statement about yourself: your likes, values, and interests ( Bainbridge, 2013).

The character provides a (protective) identity for the cosplayer, which may allow for more confident and open interactions. Moreover, cosplay dress and environment(s) permit the cosplayer to role-play the character he or she is dressed as and engage in such social activities within a “safe” and “supportive” social structure (Winge, 2006).

Taking on the persona of a manga character allows the cosplayer to express their interests and act in ways they may not normally behave. A normally shy person who admires a boisterous character like Naruto has a reason to explore a different way of behaving in an environment that would encourage Naruto-like behavior. Narratives play an important role in building self-identity. Heroes and villains help us learn different ways of navigating through life (Manifold, 2009). Impersonating them gives us a chance to see what life is like through their eyes.

Of course, with all of this we can’t forget, cosplaying is fun. The age of cosplayers ranges from the usual teens to middle-age adults and even some senior citizens (Caffrey, 2015). Fun transcends age.

The Origin of Cosplay

Now that we have cosplay defined and explained, let’s look at how it all started. Japan didn’t develop cosplay in isolation. Although, some elements of cosplay developed before its official birthdate in the 1980s. Fan cultures in the United States developed other elements which eventually merged with the Japanese to form cosplay as we now know. Let’s look at the Japanese side first.

Girls left a prominent mark on anime and manga culture, including cosplay. Shojo, or girls comics, laid the groundwork for cosplay through its full-body fashion illustrations. The post-WWII artist Junichi Nakahara pushed manga character design toward fashion with these full-body illustrations. He continued a trend started by the shojo artist Yumeji Takehisa who designed his own lines of clothing, stationary, and accessories. Shojo manga became a type of fashion magazine in addition to telling stories. Girls could buy clothing that matched their favorite characters. At the same time, girls shifted the types of stories and characters manga had through their fanfiction. Many girls would write, draw, and print their own manga to distribute at fan conventions (Kinsella, 1998; Brainbridge, 2013). This opened the door to fan-driven character identities and alternative story-telling. The combination of fashion and fan-written stories became important creative factors for cosplay.

![By greyloch from Washington, DC, area, U.S.A. (Ryuko Matoi 2) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://japanpowered.com/media/images//Ryuko_Matoi-533x800.jpg)

American science fiction merged with shojo fashion to create cosplay in 1984. When Takahashi Nobuyuki, founder of an anime study called Studio Hard, attended the scifi WorldCon in Los Angeles, the costumes of trekkies impressed him. When he returned to Japan, he wrote about the costumes and the convention’s masquerade. In his articles, he encouraged his Japanese readers to add costumes to their anime and manga conventions. He coined the term kosupure, or costume-play, for these events because the Japanese word for masquerade means “an aristocratic costume party” which was far different from the costume competitions he saw at WorldCon (Winge, 2006;Caffrey, 2015). And so Western science fiction costume competitions merged with manga fashion designs to create cosplay as we know it.

Actually, the first known costume of a manga character appeared in the US a few years before Nobuyuki’s visit. In 1979 at San Diego ComicCon International, 6 fans led by Karen Schnaubelt appeared in full manga costume. Schnaubelt dressed as Captain Harlock and her friends dressed as other Star Blazer characters (Bainbridge, 2013). However, manga and anime characters didn’t become popular until after Nobyuki’s visit to WorldCon.

Reception to Cosplay

Despite anime fans viewing Japan as a wonderland of cosplay and cosplay shops, the practice isn’t acceptable. While Akihbara and Harajuku districts of Tokyo are famous for their daily cosplay and shops, the United States accepts the practice more readily. In fact, Winge (2006) writes: “In Japan, cosplayers are not welcome in certain areas beyond the convention, and some conventions request that cosplayers not wear their dress outside the convention.” Whereas here in the United States costumes are perfectly acceptable. I remember a few years ago I saw a pair of Klingons walk into a Burger King, and the restaurant erupted into smiles and oos and aahs.

In Japan, otaku suffer from negative stereotyping. Otaku culture lacks the same negativity in the US. It helps that the US has a long tradition of Halloween and masquerades like Mardi Gras. The popularity of Star Trek also helps with this. By the time cosplay began, Americans have been dressing up as superheroes and Star Trek heroes for over 20 years (Bainbridge, 2013). Japan hadn’t adopted Halloween until recently while the US has enjoyed it in some form since the nation’s founding.

American and Japanese cosplayers differ in a few areas. For example, American cosplayers perform onstage skits as part of cosplay competitions. Japanese cosplayers strike a signature pose or recite the motto of the character. American cosplayers wear their costumes outside of conventions and put on impromptu skits. Japanese cosplayers are not welcome outside of conventions because they are seen as individualists in a culture that focuses on community values (Caffrey, 2015).

Like anime, cosplay comes from a merging of American and Japanese media culture. The emphasis on fashion found in shojo mixed with American Trekkie and superhero costumes. While Nobuyuki encouraged cosplay in Japan, Americans were pulling manga into their science fiction conventions with Karen Schnaubelt and her friends’ debut in 1979. Cosplay soon became a part of anime and manga fandom and a staple in conventions across the world.

References

Bainbridge, J., & Norris, C. (2013). Posthuman Drag: Understanding Cosplay as Social Networking in a Material Culture. Intersections: Gender & Sexuality In Asia & The Pacific, (32), 6.

Caffrey, C. (2015). Cosplay. Salem Press Encyclopedia,

Kinsella, S. (1998) Japanese Subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and Amateur Manga Movement. The Journal of Japanaese Studies. Vol 24, 2. 289-316.

Manifold, Marjorie C. (2009) Fanart as craft and the creation of culture. International Journal of Education through Art Volume 5 Number 1 doi: 10.1386/eta.5.1.7/1

Rosenberg, R. & Letamendi, A. (n.d.) Expressions of Fandom: Findings from a Psychological Survey of Cosplay and Costume Wear. Intensities: The Journal of Cult Media.

Winge, T. (2006) Costuming the Imagination: Origins of Anime and Manga Cosplay. Mechademia 1, Emerging Worlds of Anime and Manga. Pp. 65-76.

Hello,

First of all, I’d like to introduce myself. I’m Amandha and I work for Santillana Educação, here in Brazil. Santillana is part of the Group PRISA.

We publish educational books and textbooks, and our material are very well recognized and accepted in public and private schools throughout Brazil.

Right now we are working in a material named RICHMOND SOLUTION EXPERIENC 3EM, and to enrich even more our material we’d like to use the following tex:

Text: What Exactly Is Cosplay?

https://www.japanpowered.com/otaku-culture/the-history-of-cosplay

We’d like to use this text in the printed and digital version of the material, for 5,000 books and access.

As you can see it is a very modern and dynamic project that is making learn much more fun.

So, we’d like to know how we should procedure to get the authorization to use it.

Best wishes.

The correct spelling of the 1979 costumer is Karen >Schnaubelt<, not Schaubelt

Thanks for the correction!