To answer the title’s question in two words: parasocial relationships. Okay, you can return to your regularly scheduled livestream!

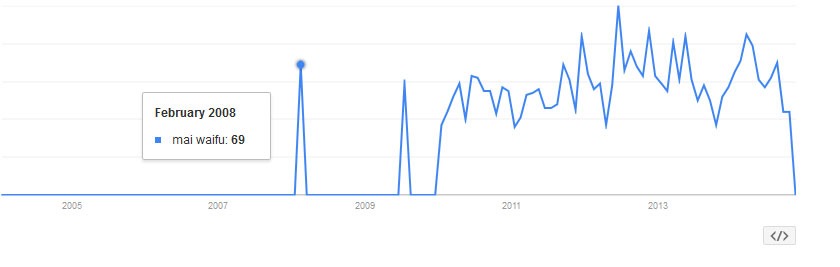

Parasocial relationships (PSR) are a common part of media consumption for many, so much that few of us stop and think about it. These types of relations extend to celebrities, politicians, livestreamers, and even fictional characters like waifus. Speaking of waifus, the use of the term has been changing since I wrote my article about waifuism. Lately, the term refers to any attractively design female anime character. It refers less to the spectrum of emotions people feel toward such characters. Waifuism is an extreme form of a parasocial relationship, but people can experience lesser forms of this relationship too.

Parasocial relationships are defined as one-sided relationships between a spectator and the persona of a performer. The definition uses the term persona because the true personalities of livestreamers, politicians, and celebrities aren’t always evidenced in their presentations. The one-sided nature makes this relationship distinct from other relationship types, which involve some sort of shared and reciprocated interaction. Performers and fictional characters cannot reciprocate (Boyd, 2024; Kim. 2024). But like standard relationships, parasocial relationships take time to develop. In the past, researchers considered TV as the main avenue, but the idea has expanded to include radio, literature, sports, politics, and social media. Livestreaming, in particular, is prone to encouraging parasocial interactions. Boyd (2024) defines parasocial interactions as:

Parasocial interactions, on the other hand, have come to be defined as the self-contained interactions that occur between a viewer and a performer, confined to the duration of the media exposure.

Parasocial interactions over time can accrete toward a PSR. In the studies I found, livestreaming was defined as playing a video game while broadcasting live, but we know there are many other types of livestreams nowadays (Sherrick, 2023). Twitch, in particular, seems to encourage parasocial interactions with its features like community-only emojis and live chats. These encourage a sense of community and interaction, as opposed to passive watching, with the performer and the rest of the viewers. This fulfills people’s natural need to join or form communities which fulfill the needs to belong and for safety. Most communities have one or more people who are seen as authority figures–usually the livestreamer in this context. All of this encourages parasocial interactions and a sense of intimacy (Sherrick, 2023):

This shared intimacy between streamers and viewers creates a unique relationship that often keeps viewers coming back to watch and can create digital communities based around those streamers.

OnlyFans and other live chats work in a similar way, and research shows this live interaction leads to more enjoyment, future viewing, and even financially supporting the livestreamer. Parasocial relationships develop over time and can develop into lasting relationships. Twitch and other two-way systems strengthen parasocial interactions and relationships because they allow viewers to consider the relationship as social whereas the livestreamer does not. This can lead to viewers sharing personal details with a livestreamer because livestreamers often share details of their lives, such as broadcasting from their homes or bedrooms–which are seen as personal spaces (Sherrick, 2023):

As one example of how this plays out on Twitch, viewers sometimes share personally traumatic experiences (i.e., trauma dump) with livestreamers, even though the livestreamer does not know the viewer personally and may not want to hear those experiences .

Livestreamers set the tone of their communities according to their persona and their authority status, but the dynamics of the group can also shift their perceptions through shared emotional connections and history (Sherrick, 2023).

Literature shares much in common with parasocial interactions with livestreamers. Reading is an active interaction with text where the reader generates characters, settings, and situations internally. This internal generation can be an even more intimate interaction than you can experience with another person because of the nature of imagining and character engagement. Character engagement involves 4 steps which can be stepped through in any order (Grizzard, 2022):

- Attention – how much attention is given to a character.

- Appraisal – how a person perceives a character’s traits and their shared similarities.

- Affiliation – the amount a person sides for or against a character according to the character’s behavior and motives.

- Assessment – how a person views a character’s behavior.

Strong and long-term engagement with a fictional character can lead to developing a PSR with that generated character. When a character shares similarities with the reader, such as age, gender, ethnicity, and so on, identification increases. And when a person identifies with a character, the narrative can lead to moral adjustment–when a person’s morality changes thanks to an encounter with a fictional character (Grizzard, 2022). This can happen without the person’s awareness. The amount of moral adjustment and strength of a parasocial relationship aligns to how the reader compares themselves to the character. According to moral foundations theory, moral sensitivities fall into 5 categories–care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity–which influences how people respond to characters. For example, people high in fairness are put off by characters who behave in unfair ways. Comparisons fall into three categories (Grizzard, 2022):

- Upward – comparing to characters who we think perform better than we could.

- Lateral – characters who perform similarly.

- Downward – characters who perform worse than we would.

Grizzard’s research shows people enjoy narratives with characters that allow for downward comparisons. Repeated exposure to certain messages and types of characters makes people (readers or otherwise) believe the the messages, behaviors, and types of people are more common than they are in reality. A good example of this would be the US’s media coverage of transpeople. Transpeople are a tiny population, but the coverage makes people believe they have more influence and population than in reality, which impacts the behavior of people who both support and do not support the population.

Even without the interaction dynamics, passively watching sports, dramas, and anime can lead to parasocial relationships, following the same processes as with fictional characters and livestreamers. Astute politicians and livestreamers understand and leverage these processes to build their followings and to influence those followings. Identification and engagement lead to this development. Scherer (2022) notes:

Because the characters on television cannot relate back to the viewer, this allows viewers to reap benefits such as placing themselves in idealized versions of everyday situations or inserting themselves into social situations, without the demands of being in genuine social situations.

Attaching to a personality shifts your relationship to the information the personality presents. As you feel more familiarity and trust–and if you consider the persona attractive–you view the personality as more credible (Kim, 2024). This can lead to you behaving as a personality suggests. Leaders depend on people who follow them with these connections. Even coercion methods require some people to believe in a leader or to have a parasocial relationship with that leader.

Waifuism, as I mentioned, is a type of parasocial relationship similar to those found within literature. Parasocial relationships can be unconscious as well, such as people who follow sports teams and particular athletes. Attaching to an athlete or a politician is the same as attaching to an anime character.

Scherer (2022) found the likelihood for developing a parasocial relationships depends on attachment styles and personality traits. People who are more open and agreeable are less likely to develop PSR, but neuroticism closely associates with PSRs. People who have higher needs create stronger versions of these relationships. Anxious-ambivalent attachment styles are the least likely to have PSRs, while secure attachment styles are more likely, especially when people feel distrustful. But when people believe these relationships are unhealthy or when others view the relationships negatively, they tend to end the relationship: no longer watching the livestreamer, anime, and so on. However, sometimes, like in the case of a PSR toward a politician or celebrity, the backfire effect can make a person cling harder to their PSR.

Parasocial relationships aren’t inherently negative. They can fulfill needs for belonging, increase self-esteem, improve body image, reduce stress, improve health and fitness, and shift perspectives for the better. The power of literature depends on a reader developing a parasocial relationship with the characters within the text in order to change your perspective. Parasocial interactions also aren’t negative–their a type of connection. But both parasocial elements can be exploited in negative directions and lead to negative perspective shifts. We naturally relate to ideas, people, animals, plants, and things. Parasocial relationships are a natural, sometimes healthy sometimes unhealthy, part of being human. Being aware of your PSRs–their strength, level of benefit, and other factors–matters more than trying to eliminate PSRs, which may well be impossible to do.

When I consider my own PSRs, my earliest are with the characters in Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain. Most of my short-term PSRs trace to books. I had a mild one with a few of the characters of Eureka Seven in my 20s, when I first started getting into anime. These relationships fulfill a variety of needs when they appear. Some PSRs develop during difficult periods, which can help you find sanctuary and wisdom for navigating through those periods. That is the strength of stories, after all.

References

Boyd, Austin, et al (2024) Construct validation and measurement invariance of Parasocial Relations in Social Media survey. PLoS ONE 19(3): e0300356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300356.

Grizzard, Matthew, Eden, Allison (2022) The character engagement and moral adjustment model (CEMAM): A synthesis of more than six decades of research. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 66 (4) 698-722.

Kim, J.; Youm, H.; Kim, S.;Choi, H.; Kim, D.; Shin, S.; Chung, J. (2024).Exploring the Influence of YouTube on Digital Health Literacy and Health Exercise Intentions: The Role of Parasocial Relationships. Behav. Sci. 14, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14040282

Scherer, Hailey, et al (2022) “Leave Britney alone!”: parasocial relationships and empathy. The Journal of Social Psychology. 162 (1) 128-142.

Sherrick, Brett, et al (2023) How Parasocial Phenomena Contribue to Sense of Community on Twitch. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 67 (1) 47-67.