Steve Shives, a Star Trek YouTuber, released a video titled “Fan Service Leads to Fan Entitlement” where he outlines how catering to fans causes problems. He argues that fan-service, defined as giving fans what they want, can make fans entitled. Entitled fans demand the story, characters, and lore to develop as they want it to develop. Shives illustrates this as fans demanding a professional sports league to throw out their team’s loss and to repeat the game until their team wins. Shives speaks specifically of people who demand and petition studios to reshoot movies that weren’t as good as many wanted them to be or played out differently, such as the Star Wars films and some Star Trek series and films.

Naturally, as I watched the video my mind turned toward anime fandom. The fan-service Shives examines differs from anime’s concept of fan-service in content, but his definition holds: fan-service gives fans what they want. Like me, Shives doesn’t have problems with fan-service if done well. It can even be fun to see hidden references. The problem, as I’ve also argued, appears when fan-service becomes the norm, the expectation, and disrupts the story and characters.

Shives points out how everything in modern life points to “the customer is always right”: making everything easy and self-focused and convenient. You can watch nearly anything you want at nearly any time. You can demand food to be delivered to you, rides to appear. I suspect part of the problem is the Internet and social media. Everyone has become accustomed to voicing their opinions as soon as they have them and otherwise having a say, however small, in how everything, including companies, function. Protests work.

While this can be good; the mob isn’t wise. As Shives’s video discusses: the audience doesn’t know what it wants until it sees it. So that means mob rule, creating by committee, leads to continued blindness. It creates a cycle of fan-service without new ideas.

New ideas come from individuals, not groups. As the Japanese proverb states, “People are people; I am I.” While everyone has a unique perspective to offer, it can only be offered as a dictatorship. As soon as you express it to the group, you become subject to group dynamics and approval; most people bend to the group under that sort of pressure. Creators have to be strong enough to dictate: this is my vision, my story, like it or not. Of course, once the vision has been dictated, it belongs to the audience. However, this doesn’t mean the audience has the right to demand the creator change her vision of the story. It’s perfectly fine for you, as the audience, to use fan fiction or some other means to show how the direction you wished the story went. This isn’t the same as what Shives discusses. Fan fiction isn’t entitlement: demanding the creator to change their ideas to match yours is entitlement.

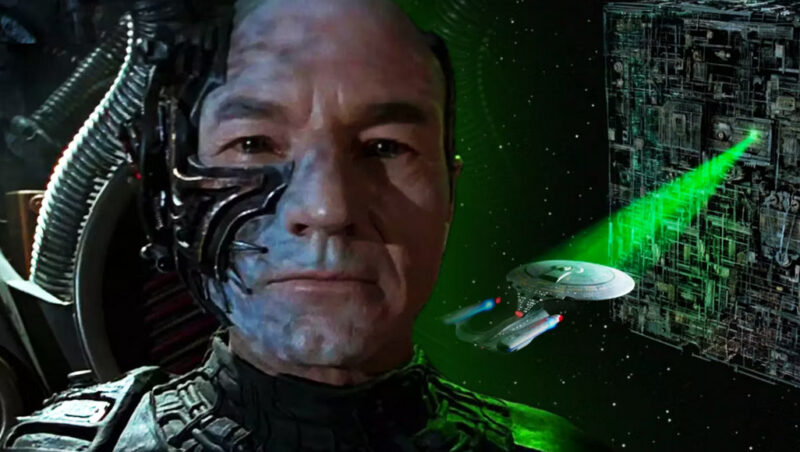

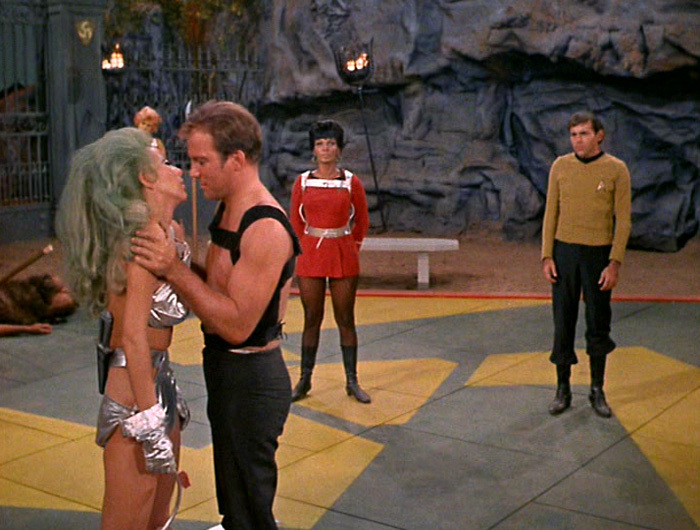

By demanding a creator to match your vision, you invalidate the creator’s message. You may not agree with that message or story, but that disagreement doesn’t give you the right to invalidate the creative ideas of others. Instead, write fan fiction. In this regard, the anime and manga community does better than the fandoms Shives deals with. If you don’t like how a story ends, you write your own version of the ending. The otaku fandom grumbles a bit, but the fandom doesn’t usually demand the author to reshoot, rewrite, and recreate. Part of this, I suspect, results from the fragmented nature of the fandom. Anime and manga encompasses a wide range of stories; whereas the DC, Marvel, Star Wars, Star Trek fandoms are more monolithic. They have set stories, lore, and characters. The properties are revisited far more often than any anime or manga properties would be. With such monolithic properties entitlement becomes more of a problem because the fans feel they have more ownership of the property but without the outlet fan fiction provides. There’s a lot of Star Trek and Star Wars fan fiction, of course, but it doesn’t appear to rise toward audience-level canon as anime and manga fan fiction can. I’ve read many Star Trek novels that are basically fan fiction, and quite enjoyed the alternative visions they provided, but those novels don’t typically enter the canon of Star Trek.

I have to agree with Shives’s assessment that fan-service leads to entitlement among a sliver of the audience. Not everyone, but a significant percentage of people fall into this. Anime lacking a beach-and-swimsuit episode would cause a few fans to rage, for example. The larger problem with entitlement stems from how selfish the perspective can be. The idea that my ideas are the right ideas, even if the my is collective, is nothing more than arrogance. If those ideas are so good, make something with them. Some elements of my novels came from my dissatisfaction with how some stories progressed. When I wrote similar scenes, I took them in a different direction. This is a proper use for dissatisfaction, not spouting off online or starting online petitions. Create your own work.

Spouting off on social media is easier, however, than putting your opinions into action. Anyone can click to sign an online petition, but not everyone can write a fan fiction or a novel worth reading. It takes practice and time and failure to create a worthwhile piece of art. Those who rage online forget that they will die. The time spent raging over a piece of entertainment cannot be retrieved. It belongs to death. It’s better to spend that time on something constructive and creative or writing a piece aimed at raising awareness like I aim to do here. As Hojo Shigetoki wrote, “Man’s fate is like the dew, and follows the uncertain wind of life and death.” You will die, so don’t waste your time spouting off online about how a film or series or story didn’t go the way you wanted. Don’t be entitled because all any of us are entitled to is death. So why rush it? Create your own version so you can learn and inspire others who are dissatisfied with your vision to create. That constant riffing is what art is about.

Sonic the Hedgehog is the number one name to know in something becoming a slave to its so-called fandom. Many video games are like this, actually, from Smash Bros. to practically anything. I take a shot whenever I see someone comment about a game not being asked for. It’s reached the point where I as a creator myself have refused to listen to other people’s opinions.

I’ve bemoaned the weirdness of some of Sonic the Hedgehog’s world but honestly I’m not familiar with that world it past what was available in 2 of the childhood cartoon series or the best Genesis games.

For me when they made the full 3d Sonic Adventure on Dreamcast or something is when I started to feel disjointed from what I thought had been the entire Sonic world. It was so weird to see a black Sonic clone holding a gun- like what is this gameplay even about. But perhaps I’m falling prey to the entitlement?

Not to take Chris’s essay here off on some tangent, but since these are good examples of what he’s saying, care to briefly describe what the issue with Smash was?

You are super entitled. You cry when the littlest thing doesn’t meet your standards.

Re: “You are super entitled. You cry when the littlest thing doesn’t meet your standards.”

You think so? That seems like a lot of conjecture, but anyway would you be willing to tell me about Smash Bros? I’m super curious…

You’re right about how Sonic the Hedgehog has fallen victim to kowtowing to fans and to the detriment of the property. Committee-created content tends to be more wishy-washy than an idea with a strong, singular vision behind it.

@Chris, that’s what I meant in my comment – it didn’t seem like there was a central core to the identity of that IP. When you say wishy-washy I say scattered.

But, I clearly have no idea where it was capitulating two fans. When I was young there were two totally different Sonic the Hedgehog cartoons with extremely different tones. One was more loose and light-hearted shenanigans (they even had to give Sonic a trademark food that he loved – chili dogs!) while the other one was very serious and cool. So there were already two very divergent visions of who and what Sonic was.

Do you have any details on how it gave in to fans?

I’m too old to know anything about the Sonic cartoons, and I never cared for the games. I can’t really comment on how Sonic has been ruined for fans because of fan-service, other than I’ve read many complains online to that fact.

Hullo @Taylor,

I’m not sure about your hyperbole, but I am very curious about Smash Bros- do you care to share how fans ruined it? Even though I haven’t owned a system in over a decade, I love playing it any chance I get, so I’d love to hear anything you feel like sharing about it

Wow, shots fired by saying that we’ll all die someday. The thing is that most Western fans hate thinking about death and/or don’t know how to talk about it in a way that helps and heals.

When I studied Bushido, I was surprised at how the adage “remember death” underpinned all its moral philosophy. It would do society well to take up that adage in a healthy way. We might see less needless infighting, fruitless living, and other problems if everyone would hold death in mind and use their limited time well. It isn’t a comfortable realization, however.

I suppose American politics could be considered the ultimate form of fan service, its messages written to conform to committee surveys. More interesting to consider is what motivates the creators, and ultimately the resources behind them. Art can certainly emerge as a new or profound creative expression; but few artists survive for long without patrons. And that implies that there always exists some pressure for an artist’s work to degenerate over time, evolving into an echo chamber for those to whom it appeals. Perhaps this explains much about why the Kubricks, Kurosawas and Miyazakis appear as rare exceptions, with most profound works existing as sporadic episodes recognized only after the deaths of their creators (or of their franchises).

That’s a good point about American politics! Except, unlike with media, the promises of fan-service aren’t always delivered. You’re right. If you look at history, few artists were able to make a living with their art without a patron. The greatest artists of the Renaissance all had wealthy backers. Michelangelo had the Catholic Church and the Pope, for example. Writers rarely made a living through their writing, and those that did often had to write what they didn’t like to write. Their best works were side-works in many cases.