In Confessions, Saint Augustine contrasts the love of learning with the love of spectacle. His friend Alypius disliked the gladiatorial games of Rome. One day Alypius’s friends convinced and bullied him to join them for a round of games. The excitement of the bloodsport captured him. As Augustine wrote: “Without any awareness of what was happening to him, he found delight in the murderous contest and was inebriated by bloodthirsty pleasure. He was not now the person who had come in, but just one of the crowd which he had joined, and a true member of the group which brought him. (VI: VIII)”

Translators use the English word curiosity for Augustine’s word curiositas. However, Augustine means more than curiosity. Alypius looked because he became curious. However, that normal curiosity developed into something beyond wanting to learn and experience something new. As Augustine writes, Alypius becomes an avoid gladiatorial game-goer. He becomes a lover of spectacle.

Spectacle and learning exist on a spectrum, like most things. Spectacle can spark learning and learning can lead to spectacle. Spectacle is the surface level of experience. It involves high emotions like excitement, curiosity, anger, and other intellectual and emotional highs. However, spectacle doesn’t encourage learning at its extreme. Pornography is perhaps the greatest example of spectacle. Spectacle requires escalation in order to achieve the highs that drew you toward the spectacle in the first place. That is why porn users have to seek increasingly violent, strange, or extreme content. That is why thrill seekers have to get ever more daring. Over time, you become used to spectacle. It becomes boring.

As Zena Hitz (2020) writes: “In the supremely shallow realm of acting for the act of acting and a preoccupation with spectacle, growth is impossible. All that lies there is an endless, repeated sequence of increasingly joyless thrills. Our sense of emptiness and lack of satisfaction are signs that we have not in fact attained any human goods or actually connected with other human beings. The dissatisfaction is a sign that we long to attain real goods, and that we long to bond with others in truth, in the depths, and not remain at the surface of things.”

The love of learning involves the enjoyment of looking deeper, of going beyond the initial spectacle to understand why, how, what goes on. Augustine and his other friends also had seen gladiatorial games. Unlike Alypius, the spectacle sparked them to ask questions and to study what drove people to such events, to question the cultural norm of such violence. Hitz (2020) writes: “But we know by now that the person governed by curiositas is more like one addicted to violent video games, and we might guess that the serious person is one who, like Augustine, restlessly pushes for the better, the truer, the more profound.” Later in her book, she adds: “So too a culture saturated with spectacles appeals to our desire to experience for the sake of experiencing, to dwell at the surfaces of things, to seek out a false communion with others that consists of being mutually spectators and spectacle. We can withdraw from the world, so to speak, and enter a realm of empty thrill seeking.”

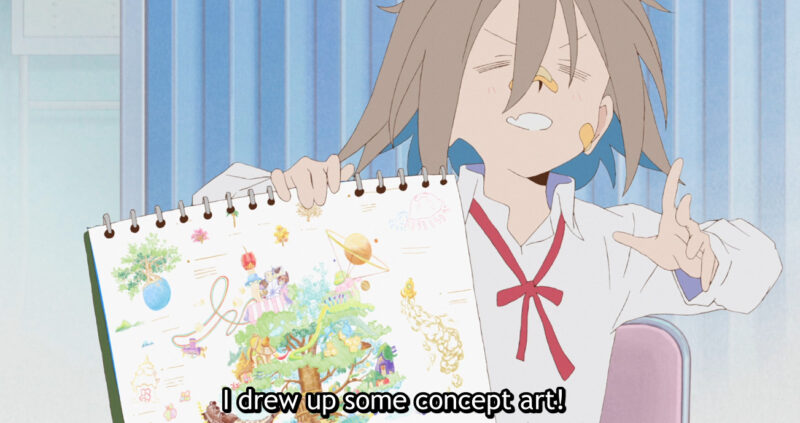

Spectacle and Anime

Hitz and Augustine agree that learning and a rich inner world gives life meaning and pleasure. Learning and a life of contemplation reveals the path to the good. Aristotle also points to how a life of thought leads to happiness: “The life of the intellect is the best and pleasantest for man, because the intellect more than anything else is the man. Thus it will be the happiest life as well.”

Anime can be a spectacle. In fact, many otaku remain at the surface level of their fandom, seeking ever more anime and arguing with others about their favorite characters. Spectacle, as we have seen, involves community. The intellectual life, as Augustine, Hitz, and even Aristotle imply, needs solitude. Now there’s nothing wrong with the communal nature of anime fandom. Humans need social interaction after all. However, when the fandom influences you as Alypius’s friends did, you risk losing long-term happiness. You can get lost in the ever-changing sea of spectacle. Many anime fans remind me of sports fans. Both seek the excitement of the new. Both enjoy the tribalism of siding with their favorite team to the exclusion of others. All of this is spectacle. It is the surface level of understanding.

As a reader of JP, you are interested in more than spectacle. Anime points to deeper cross-cultural, psychological, and literary ideas. Anime points to deeper learning if you follow it. Or anime can lead to the empty thrill seeking Hitz warns against. Of course, a little empty escapism is fine if you do it intentionally. However, a life of it is, to be blunt, a wasted life. As a librarian I see people who spend inordinate amounts of time watching movies. Now, if they used movies to go deeper into learning about cinema, just as I use anime to delve into Japanese literature, then they are living an intellectual life. An intellectual life is about the pursuit of learning for its own sake and sharing it with others who want to learn too. The object of learning, and learning always needs a object, doesn’t matter. Every spectacle can unlock depths of learning. Even pornography or hentai can lead you to study human sexuality, media culture, psychology, cinematography,art, script writing, history, economics, and more. Unfortunately, few people delve beyond the surface of a spectacle that mesmerizes them.

Those who love to learn take pleasure in being proved wrong. Not only does this correct your knowledge, but it can lead to more questions. An intellectual life seeks to be proven wrong. Beware those who don’t want to be proven wrong. They often exist on the level of spectacle without realizing it.

Only you can decide what sort of life you want. Not every spectacle needs pursued for learning. There isn’t enough time to pursue everything. However, love of spectacle differs from enjoying some spectacle. If you have an intellectual life elsewhere, all is well. If you don’t have an intellectual life of some sort, you deprive yourself of the happiest life.

References

Chadwick, Henry, trans. (2008) Confessions Oxford University Press.

Hitz, Zena (2020) Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life. Princeton University Press.

Thomson, J., trans. (1953) The Nicomachean Ethics Penguin Books.