For example, otaku culture has its own language. Understanding that language gives you access to the conversations and ideas within the subculture. As ideas change, the language changes–such as the fluid use of the word waifu to include male JoJo Bizarre Adventure characters in various memes. But mastering a language doesn’t mean you master the culture, as many English-learners have told me. They struggle to fully understand American culture’s oddities that I, as a native, don’t give any thought. Kramsch (2013) expresses this problem:

[Language learners] cannot understand the Other if they don’t understand the historical and subjective experiences that have made them who they are. But they cannot understand those experiences if they do not view them through the eyes of the Other.

In other words, language may help you get into a culture, but it won’t help you understand that culture because you haven’t lived it and studied its history. Kramsch suggests that you don’t necessary need to learn a culture’s language to understand that culture. In fact, language learners can’t leave behind the culture of their birth and upbringing. That culture will continue to act as a filter for any language we learn (Kramsch, 2013):

Part of what it means to learn someone else’s language is to perceive the world through the metaphors, the idioms and the grammatical patterns used by the Other, filtered through a subjectivity and a historicity developed in one’s mother tongue.

Fortunately, our filter can expand through the study of other languages and cultures. But all of this suggests language is a part of a culture, but it isn’t the culture.

The Poles of Human Understanding

Culture acts as an expression of human understanding while influencing that understanding. It exists in both our minds and outside our minds in the material world as shaped by our minds (a little confusing, I know).

Mironenko (2018) reduces this complexity to two poles of human understanding:

- The individual human acts as the “pivot of reality,” reality that is observable, measurable, and real.

- Social institutions and other external objects can be fuzzy, liquid, and less real. Social structures and “social facts” exist here.

Let’s break this down. Humans act as a “pivot of reality” because we can observe and measure and define the physical world so we can understand it. Reality exists to us only after we observe it. Germs didn’t “exist” for people until they were discovered. People used to get sick because of an unbalance of bodily humors (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood according to Western thinking).

Social institutions lack the basis of reality. They are ideas people agree upon that cannot be measured or observed objectively. They exist as part of a consensus. When the consensus changes, the social fact changes. Sometimes the changes happen because of a discovery of reality, such as the discovery of bacteria as the cause of illness.

Hard facts exist separate from social facts, that is, human understanding of the physical world. A good example of this sits in today’s gender debate. On the object side, three genders exist based on genetics: XY, XX, and hermaphroditic (I know this word is offensive to some) genetics: XXY, XYY, XXX. Of course, hormones also influence physical gender, but hormones don’t influence DNA. However, social fact deals with people’s perception of their gender as opposed to their genetic gender. Social fact is in the process of changing, so the terms are in flux. But this perception isn’t measurable. It’s based on consensus that is also entangled with the sexual orientation social facts which are in flux. Confusing the two doesn’t help the evolution of gender social facts. But social facts and institutions are messy. After all, the human mind is a messy, unorganized workspace!

These two poles of understanding form the groundwork for culture. Culture extends from reality and general consensus of social facts. Social facts change the individual who also changes those facts according to Mironenenko (2018). Individuals are “empowered to create, destroy, and change the external reality following his purposive plans, desires, and visions….This ‘extrasocial cosmos’ empowers individuals to transform the reality according to purposefully and freely chosen identities – rather than making him obey to the existing rules.”

The sum of all these individual actions eventually create the rules that form a culture and influence the individual’s thought process.

Let me illustrate with the gender debate. People who hold the “old” two-gender social facts are still following their empowerment and freely chosen identity, influenced by past social facts. Two differing social facts clash when one group tries to force the other to “obey to the existing rules” or follow the existing consensus. It becomes a conflict about what rules define the culture, which is why people often grow violent in defense of their side. A change in social facts threatens a person’s sense of self. People have the right the choose their social facts, but they do not have the right to force those social facts on others or discriminate. With time, a consensus will emerge. With more time, that consensus will become the unconsidered norm until some new social fact comes along to upend it. And the process will begin anew.

These two poles of human understanding shape the form of a culture’s material and thought objects. As the understanding of reality changes and as social facts change, you see shifts in architecture, jewelry, literature, language, and even the approach to aging. Successful aging, for example, has changed as human life spans changed. In a world where people lived to 32 on average, the idea of a teenager didn’t exist. By the time a girl had her first period, she was middle-aged. Likewise, teen boys had to become adult men at the same age. But as we discovered germs and sanitation and nutrition, life spans expanded (I must note that this is in debate. Old age was common in the ancient world, but it didn’t appear to extend to the majority of the population as it does now). The concept of being a teenager, including the literature, fashion, and language associated with it developed within culture. Now we consider it a part of normal life.

The expansion of life span has also changed, but the perspective of it also varies by culture. Tam (2014) illustrates that “ideological values matter more than material contributions among Canadian Inuit elders as far as successful aging is concerned” whereas in American culture aging well focuses on health and wealth.

What is Culture?

With all of these examples out of the way, what then is culture? Culture is the sum of material objects (the first human pole of understanding) and literature, languages, art, science, and spirituality (the second pole of understanding). It is the consensus of rules people define and are defined by. These rules define how people view reality and approach problems. Culture is internal and external.

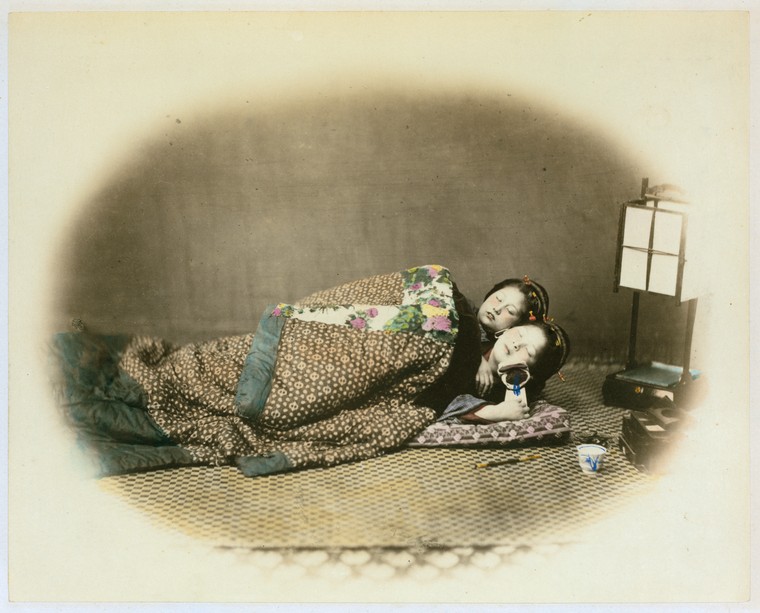

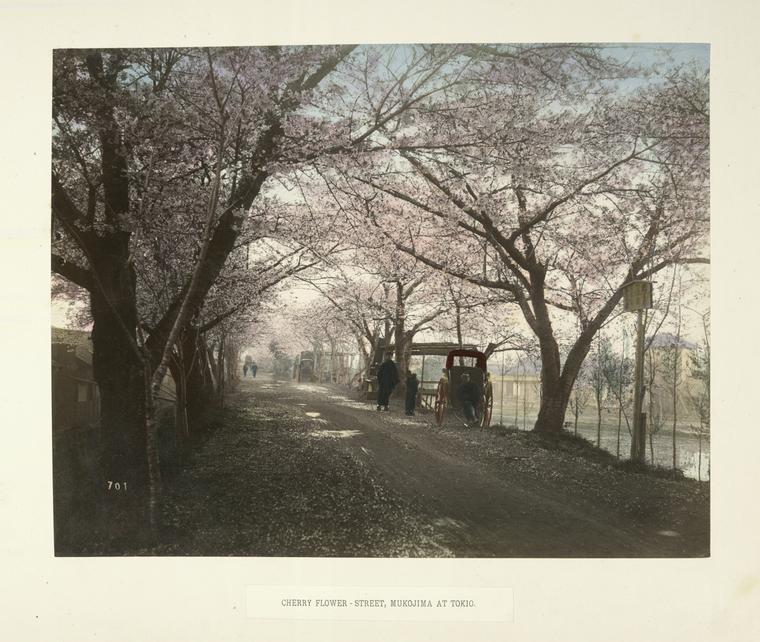

Over time, cultures change and merge based on discoveries in reality and changes in social facts. American culture and Japanese culture illustrate this. American culture merges British, French, Irish, Chinese, Japanese, and other cultural elements with the American people acting as a mediating consensus. Japanese culture consciously merged British, American, French, Prussian, Chinese, and other cultures. Again, mediated by consensus.

Culture is a collective expression of people influencing each other as they negotiate life. Social institutions result from this negotiation.

Subcultures like otaku culture also follow this formula. Culture used to be slow to change, but the Internet has allowed for change to accelerate. This acceleration of change causes much of the conflict we see now. People don’t have time to adjust or consider before lines are drawn and rules are formed. In fact, this acceleration has become a social fact itself. It will take some time for this problem or benefit (depending on which side you stand) to reach a consensus.

References

Kramsch, Claire (2013) Culture in foreign language teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 1(1) 57-78.

Mironenko, Irina & Sorokin, Pavel (2018) Seeking for the definition of “culture”: current concerns and their implications. A comment on Gustav Jahoda’s article “Cultural reflections on some recent definitions of culture.” Integer Psych Behav 52:331-340.

Pagel, Mark (2017) Q&A: What is human language, when did it evolve and why should we care? BMC Biology 15:64.

Tam, Maureen (2014) Understanding and Theorizing the Role of Culture in the Conceptualizations of Successful Aging and Lifelong Learning. Educational Gerontology. 40: 881-893.