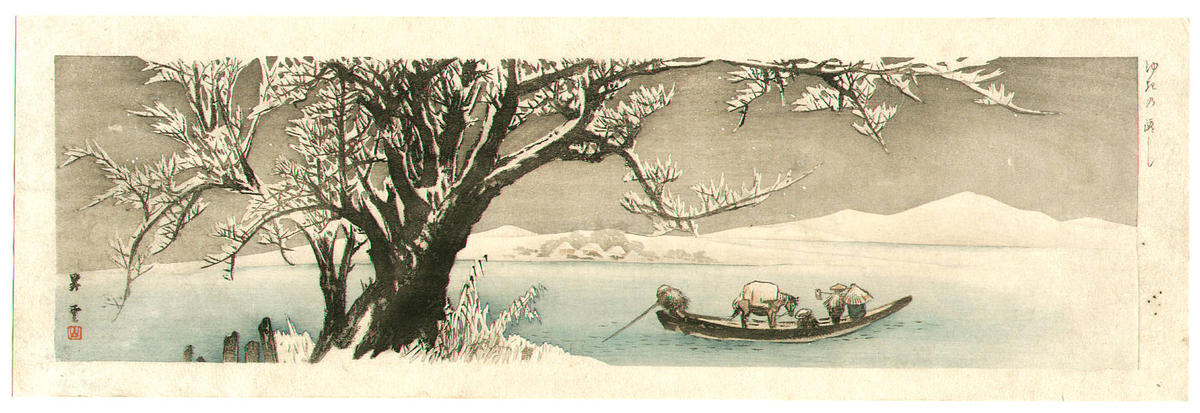

Tsundoku’s etymology is a bit of a mash up. Tsun comes from tsumu–to pile up–and doku is verb that can be used to refer to reading (Gerken, 2018). But the mash up word could also come from tsunde–to stack things–, oku –to leave for awhile– and doku–to read (Brooks, 2017). But in either case, the word doesn’t have negative connotations unlike the Western word bibliomania. Bibliomania–the intention to create a book collection and read all of it–was seen as a problem during the 1800s. Some collectors spent their fortunes on their libraries (Brooks, 2017). Bibliomania has softened a little in its negative feeling, but mania isn’t exactly a positive term in English! It implies lack of control. Some bibliophiles can lack control, but most I know collect based on certain criteria or with certain goals in mind.

Now it would seem tsundoku would be a waste of space and money. After all, you may have the intention of reading the pile, but you never really get to it because it never stops growing. You just shift it around to make space for more. Your good intention to read never matches your time and energy. However, it’s good to have a collection of unread books designed as an antilibrary, a term coined by the scholar Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Taleb calls a person who focuses on unread books an antischolar. These people, Taleb argues, are soothed by the unknown. They focus on what they don’t know and on how to find the information when they need it. So they design the library to fill the gaps in their knowledge. Their libraries focus on what information they could need in the future rather than what they need in the present (da Col, 2015). As you can imagine, this can be hard to achieve. There’s always more we don’t know than we do know. Plus, knowing what we don’t know can be a challenge. While you can argue the Internet is an antilibrary, one that’s on demand, it lacks the depth a good book on a topic can provide. And the accuracy of the information is often suspect; the Internet lacks the vetting done on good books. Fortunately, a good antilibrary only needs a single good book for most topics you don’t know about.

As a librarian and wannabe scholar, I have my own, small antilibrary, but as a (pseudo)minimalist I also only want books that I’ve read and will reread to maximize my space. However, I’ve discovered as a librarian and researcher that many books are unavailable in the library system and limited in print. Often, I can’t find them online either. I’ve started collecting these books when I can for JP articles and other projects. And when I do find these books online, I’ve discovered they’ve sometimes changed against their print versions.

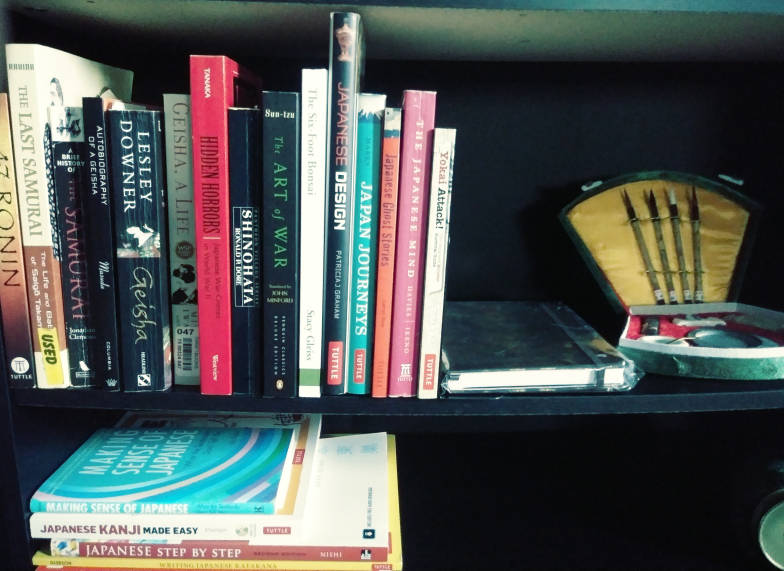

In any case, because I organize for research, I fold my unread books into my collection; whereas, tsundoku typically keep their unread books together. I organize my library by category–Japanese research, Christianity, Buddhism, Classical Antiquity, Art, Fiction, etc. Within each category, I alphabetize by title. Now, as I librarian, I know I am supposed to use the author’s last name. But I find category > title superior for browsing for a book I need in my limited collection. However, folding unread books into my shelves often means I forget about them. But as an antilibrary, this comes in handy. The books await a serendipitous rediscovery when I need them.

Tsundoku points to a strange view we have toward information. We often view it as a property to consume or hoard, as if information is somehow limited in supply. But it is partially right. After all, some books fall out of print and their information becomes lost. Tsundoku points to the joy of discovery and not wanting to spoil the fun of the unknown inside of a book. I’ve stared at an old book wondering what goodies hid inside it–illustrations, stories, and knowledge. Reading the book ends the anticipation and the joy that brings. Tsundoku captures the joy books as an object can bring. After all, the books people collect shows their interests and the gaps in their knowledge. A book collection shows concerns, doubts, fears, joys, tastes, and who a person is.

So do you practice tsundoku? What does your book collection reveal about you?

References

Brooks, Katherine (2017) There’s A Japanese Word For People Who Buy More Books Than They Can Actually Read. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/theres-a-japanese-word-for-people-who-buy-more-books-than-they-can-actually-read_n_58f79b7ae4b029063d364226.

da Col, Giovanna (2015) A Note from the Editor: Tsundoku. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.14318/hau5.2.001.

Gerken, Tom (2018) Tsundoku: The art of buying books and never reading them BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-44981013.

Sanders, Ella Frances (2014) Lost in Translation: An Illustrated Compendium of Untranslatable Words from Around the World. Ten Speed Press.

Thank you for the article, I’m glad to discover there’s a word for this and that it’s not just me!

I tend to store most of my books digitally and then have those that are either illustration based, rare or my favourites in physical (hardcover) where possible. Of course, digital never has quite the same feel as paper itself but it’s good enough with a proper electionic paper device. I also categorise Category -> Title, it’s just easier on the mind when recalling books.

Wonder if “tsundoku” will change in the future to also apply to saved social media posts and internet bookmarks which end up the same or will strictly stay to applying to books?

That’s a good question. Digital to-read lists aren’t as visible, however. Plus, vendors can always delete your posts, bookmarks, and even ebooks from your device. I suspect we may develop a word more associated with ephemera for digital to-do lists. English likes to adopt foreign words, so it’s hard to judge which word will take the role.