Talismans, amulets, and good-luck charms appear throughout anime. Japan isn’t unique for having these–every culture has their own version–but Japanese charms have become a bit more international with their appearance in manga and anime. Some work similar to the American lucky-rabbit’s foot. Others are rather different.

Talismans and other charms overlap with toys in Japanese culture. Some objects intended for children find their way into temples and shrines, blurring the division between charm and plaything (Kyburz, 1994). Toys and charms often fall under the category of “folk toys” as Saito Ryosuke (Kyburz, 1994) characterizes the category:

- Made of cheap, everyday materials like clay, wood, bamboo, paper etc.

- Handmade and represent the local craft

- Sold in shrines and temples. Often associated with folk beliefs of protection from disease and misfortune, wishes for a happy and long life, prayers for abundant crops.

- Linked with local costumes and home rituals such as seasonal festival decorations. Have a strong link with seasonal events.

- Beginnings trace to the Edo or Meiji period, prior to industrialization.

It’s a little confusing, but think of the Daruma doll as an example of a folk toy. Children play with it, but it also has the properties of a good-luck charm. The doll is supposed to be the likeness of the Indian Monk Bodhidharma, who is a legendary patriarch of Zen, sitting in meditation. This explains why the dolls don’t have legs or arms. It symbolizes the idea of recovery and to ward off misfortune. In the Meiwa era (1764-72), a priest had so many requests by peasants to reproduce the charm, that he entrusted the farmers with its production, giving them a wooden sculture of Daruma as a model. The farmers eventually combined their paper-mache Daruma dolls with children’s weighted tumbler toys to make the Daruma we know now (Kyburz, 1994). The dolls is both a toy and a talisman.Talismans come in many shapes and sizes. The well-known cat statue seen in shops and homes, called a maneki-neko, is a good-luck charm.

Amulets are another common talisman. One of the most common in Japanese history is the netsuke. Netsuke are small sculptures that secured the cord of a carrying-gourd or carrying-box to a person’s sash. Kimono and other traditional Japanese clothing lack pockets. The sculptures had various properties based on their shape. The gourd-shaped netsuke is said to prevent the wearer from stumbling and falling. It dates back to at least the Genroku period (late 1600s) and were warn by the elderly until at least the early 1900s. Gourds were often used to preserve and protect things, so the association of its shape with these uses carried over the the netsuke. The shape would ward spirits that would make people fall (Holdburgh, 1919).

While we can think of netsuke and daruma as good-luck charms, the Japanese concept of luck differs from our Western idea of luck in a few ways. Luck “implies the existence of agency, good or bad, outside the control of the human individual. (Daniels, 2003).” Charms and rituals provide a means to beseech those agencies to act in our favor. In my area of the United States, we “knock on wood” to ward off misfortune, for example.

In Japan, the spiritual is present in all areas of life, and people may use religion to help them achieve success and prosperity (Daniels, 2003). Most religions have a prayer system designed to intercede–to create luck, if you will–for us. But most religions, including Shinto, have professionals that control access to spiritual power. Talismans and good-luck charms let people interact with the spiritual world without needing those professionals. The spirit world can be engaged in simple actions like ringing bells, offering money, or rubbing statues.

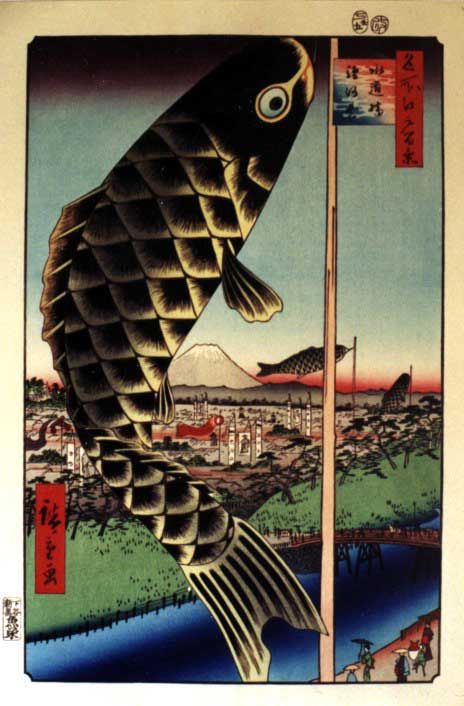

“Luck plays a significant role in everyday life in contemporary Japan,” according to Daniels (2003). For example, during the New Year period, people purchase engimono, things that bring good fortune. Shines and temples sell good-luck arrows and the brocades silk charms we in the West associate with Japanese good-luck charms.

So luck appears everywhere, and it is defined by a mix of two different ideas (Daniels, 2003):

- The Buddhist idea of karmic causality.

- The Taoist idea of time’s cyclical nature.

The Japanese idea of luck involves some responsibility for your actions. People can change their destines through rightful action. Bad luck can be averted by taking spiritual precautions. These actions can help you curb the cyclical nature of misfortune.

Engimono act as spiritual precautions, allowing people to connect to certain deities that can provide help to those that seek them. Notice that this isn’t a passive system. It requires action. Sacred rice-scoops, made from sacred trees on the island of Miyajima, connect with the veneration of the deity Benzaiten, a good-luck deity, for example.

Engimono can be anything, but they don’t have to be connected to a specific deity or sacred site to work in the Japanese concept of luck. Tools and utensils are the most common–again, to tie together the idea of action with luck. It also ties with Buddhism’s respect for all inanimate things. Less is more too. Engimono reduce in power as you collect more of them. It’s a matter of quality over quantity.

Christianity has its own version of engimono. Think crucifix necklaces, prayer beads, lucky horseshoes, rabbit’s feet, and other items.

Good-luck charms of every sort remain a part of being human. Every culture has its own rituals and charms to beseech the realm we encounter but rarely. Japan has charms for cat health, dog health, human fertility, good luck, prosperity, long life, and just about every other human concern. Good-luck charms and talismans are physical representations of prayers and the well wishes of other people.

Some self-styled modern people scuff at the idea of good-luck charms and talismans, but it does us well to have a little mystery and appreciation in our lives. Charms teach us this and teaches reverence for the objects around us. In our age of mass-produced consumer goods, we’ve lost appreciation for how objects make life more comfortable and the life hand-made objects have. The act of making something by hand transfers a small part of the maker’s life into that object for you to possess (their time, their skill, their thoughts). Finally, receiving a charm as a gift (as I have several times) shows how much the giver is thinking of you. They want you to be well, happy, and prosperous. Gifting charms can be a signal of love.

References

Daniels, Inge Maria (2003) Scooping. Raking. Beckoning Luck: Luck, Agency and the interdependence of people and things in Japan. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 9 (4). 619-638.

Holdburgh, W.L. (1919) Note on the Gourd as an Amulet in Japan. Man. 19. 25-29.

Kyburz, Josef. (1994). “Omacha” : Things to Play (Or Not to Play) with. Asian Folklore Studies. 53 (1) 1-28.