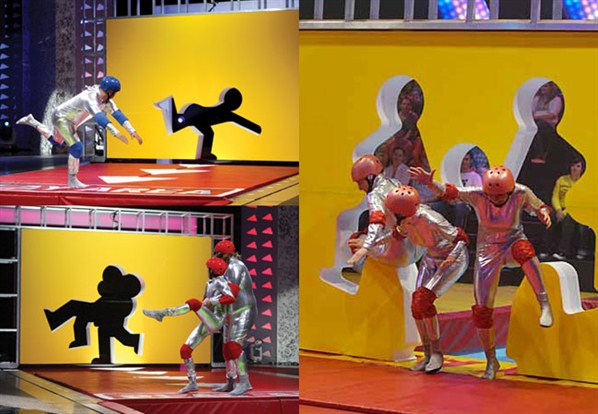

Okay, the title of this post is click bait, but from a Western perspective, Japan is strange. Most lists focus on the rare oddities of Japanese culture like panty fetishes, vending machines, and game shows. Let’s approach the topic from a different angle. There are some strange aspects of Japanese culture that go beyond the typical list.

Cultural Affection for Animation

In the US, studios aim animation at children with a few exceptions like Family Guy and The Simpsons. However, in Japan, as any anime fan knows, people accept animation. Cute animated characters serve even as logos. If anything, the American view of animation is weird. I view animation as a storytelling medium as valid as live action. But let’s set that topic aside and look at Japan from an American Western perspective.

Japan’s acceptance of animated fictional characters has roots in Shinto, Japan’s main religion. Shinto teaches everything has a spirit, much like Native American beliefs. This includes rocks, trees, water, and other elements of nature. This makes it easier for Japanese to feel personal connections to inanimate objects like anime characters. They too can have a spirit. While this isn’t a conscious idea, the environment Shinto beliefs create sets the stage for an unconscious view. Marketing efforts also contribute to the idea. Companies in Japan pitch cute characters frequently to adults. This allows adults to feel an affinity toward the character, much like sports team branding does here (Baseel, 2014). The Edo period’s popular woodblock prints and puppet shows contribute to Japan’s embrace of animation. Woodblock prints laid the foundation for manga, and puppet shows often performed the stories woodblock prints retold.

It helps that Japan loves Disney. Walt Disney, after all, inspired the father of anime and modern manga Osamu Tezuka. Disney’s Frozen became Japan’s third highest grossing film, after Titanic and Spirited Away (Blair, 2014). Two of the highest grossing films came from animation studios. Whereas here in the US live-action superhero movies blow out box offices.

Long History of Robot Obsession

Speaking of puppet shows, Japan has a long history of using robotics as a form of entertainment. Called karakuri, these devices were used to trick or tease people. Karakuri came in various types. Japanese puppet theaters featured automated puppets for centuries. Other puppets served tea or shot arrows. Nihon Shoki — known in English as The Chronicles of Japan, the second oldest book of Japanese literature–mentions the first karakuri: the South Pointing Chariot, made in 658 AD. It always pointed south and acted as an early compass. The technology came from China through clocks and marionettes. This ancient form of robotics took off when the Christian missionary Francisco de Xavier introduced Western mechanical clocks around 1551. Japanese clock makers began to use clock springs to store energy, allowing karakuri to move on their own (O’Shea, 2015; Yan, 2009).

The most famous karakuri ningyo, or mechanized puppet, is the chahakobi ningyo, the tea-serving doll. A host places a teacup in the doll’s hands, and it moves toward the guest. It stops in front of the guest who takes the cup and drinks. When they return the cup to the doll, it turns and walks back to the starting point. A book from 1690 describes this robotic doll, and in 1662, hosts used tea-serving dolls to entertain people. Takeda Ohmi introduced marionette performances that featured these mechanical actors. Troupes focused on this continued into the Meiji period.

Another doll called sake-kai, designed by Iidzuka Igashichi, automatically walked into a sake shop and buy sake, but no examples survive. Another doll picks up an arrow from the table and shots it from a bow and then repeats the motion. Still other dolls could write calligraphy and perform other actions.

Here in the United States, we fear and resist robotics. For some they mean doomsday. Think the Terminator movies. For others, they mean job losses. Still others are excited by the possibilities. But we lack the history Japan does with robots. Masahiro Mori, a roboticist, suggests Japan may have had more fertile ground for the acceptance of robotics (O’Shea, 2015):

“Even if Buddhism and Shinto contain nothing that intrinsically promotes robots, the argument goes, they contain nothing to hinder them, whereas Christianity does. Since Japan is dominated by the former, it must have less resistance to robots.”

Mori’s comments link with the reason why animation is more accepted in Japanese culture: the idea that inanimate things have a spirit. Judaeo-Christian tradition teaches against this idea, which underpins some of our resistance to animation and robotics. Modern Japanese fascination with robots also results from science fiction anime. It’s thought stories like Astro Boy and Neon Genesis Evangelion make Japanese culture more open to robotics than American culture (O’Shea, 2015).

We think of robots as machines made of steel and plastic, but karakuri were made primarily of wood. You could say Japanese culture revolved around wood. Mineral resources are scarce. This leads me to the next strange aspect of Japan.

History of Environmentalism

Other than rice, wood was the most important resource of ancient Japan. It was used for construction, heat, and other uses. Considering this, you’d think Japan would be barren of forests. Well, 67% of Japan’s land area is forested (Convention on Biological Diversity, nd).

Japanese culture has a long history of environmentalism because of their reliance on wood and because of their isolation. For those of us in the West, this historical environmentalism strikes us as little strange. We have a habit of clear cutting for farms. Our towns tend to sprawl. In medieval Europe, peasants viewed forests as threatening. They housed bandits and devils. However, Japan wrestled with the same issues we have in the West. Japanese folklore speaks of dangerous creatures lurking in deep forests.

Several times through Japan’s history, deforestation became a severe problem. The amount of wood needed to construct Japan’s castles and cities was enormous. And some of these wooden structures still stand. The oldest wooden structure is a temple Horyuji, made from old growth Japanese cypress. It dates to over 1,000 years old. During the 17th century, Edo ranked as the world’s largest city and would remain that way until the 19th century.Edo was mainly built of wood (Iwamoto, 2002).

However, Japan wrestled with the same issues we have in the West. Japanese folklore speaks of dangerous creatures lurking in deep forests. Several times through Japan’s history, deforestation became a severe problem. The amount of wood needed to construct Japan’s castles and cities was enormous. And some of these wooden structures still stand. The oldest wooden structure is a temple Horyuji, made from old growth Japanese cypress. It dates to over 1,000 years old. During the 17th century, Edo ranked as the world’s largest city and would remain that way until the 19th century.Edo was mainly built of wood (Iwamoto, 2002).

Several times through Japan’s history, deforestation became a severe problem. The amount of wood needed to construct Japan’s castles and cities was enormous. And some of these wooden structures still stand. The oldest wooden structure is a temple Horyuji, made from old growth Japanese cypress. It dates to over 1,000 years old. During the 17th century, Edo ranked as the world’s largest city and would remain that way until the 19th century. During this period, Edo was mainly built of wood (Iwamoto, 2002).

The first effort to stop deforestation was in Kiso after more than 100 years of war.

In 1665, Kiso’s feudal lord introduced seedling protection and selective cutting to preserve the resource. The effort failed. The second reform of 1724 succeeded, allowing Kiso forests to recover while meeting needs for timber (Iwamoto, 2002).

From an American perspective, these efforts to reverse deforestation are strange. Good, but strange. Environmentalism has never been high on our priority list. Mainly, this is because the North American continent is large and rich in resources. It takes disasters like the Dust Bowl for us to take conservation measures. Whereas Tokugawa Japan acted before their environmental problems became disasters of Dust Bowl magnitude. The top-down authority of the period, and people’s acceptance of that authority, allowed the country to move proactively.

This feature of Old Japan feels the most alien for us Americans. We don’t accept orders in that way. Well, we do but we don’t like to think of ourselves as doing so. In any case, Japan’s isolation played a role in this proactive environmentalism. The Tokugawa shogunate had a vested interest in long-term management of forests because wood built the foundation of the country. Without it, they faced death and an end to their long reign.

Westerns view Japan as modern and urban, which it is. But the country’s vast forests and rural mountain villages rarely enter our perspective of Japanese culture. Realizing 67% of Japan is forest goes against typical thinking. Japan has another open secret that surprises us: Japan is predominately non-Christian.

Christianity Failed to Make Significant Inroads

Americans like to think of Japan as Western, and Western means Christian. But less than 1% of the population is Christian (Hoffman, 2014). Francisco de Xavier had an initially positive view of Japan when he landed in Kyushu in 1549:

“In my opinion no people superior to the Japanese will be found among the unbelievers.”

However, when he left Japan two years later, he had changed his tune. He called Japanese Buddhism “an invention of the devil.”

The first Christian daimyo was Omura Sumitada, who converted in 1562. His land included Nagaski, which was destined to become a vital trade hub. The economic and cultural threat Christianity posed roused the most powerful lord of the time. Toyotomi Hideyoshi decided put an end to the spread of Christianity. Over a period of 40 years, he executed Christians and drove the religion underground. Christianity never recovered.

How could actions so long ago leave such a long effect? Why does Japan embrace baseball and celebrates Christmas but Western-influenced Christianity languishes? After all, China has 52 million Christians despite regulating the religion. South Korea’s Christian population hovers around 30% (Hoffman, 2014). Today, Japan doesn’t actively persecute Christians. So why doesn’t the religion grow?

According to Minoru Okuyama, director of the Missionary Training Center in Japan, the Japanese focus on harmony is the strongest barrier. They “are afraid of disturbing human relationships of their families or neighborhood even though they know Christianity is best.” Japanese culture values relationships above everything else (Hoffman, 2014). They see Western Christianity as divisive. This is one of the reasons that drove Hideyoshi’s successful effort to tamp down the religion.

For Western Christians, this is certainly strange. After all, we consider Christianity good and healthy. Christianity focuses on the family as well! However, Shinto Buddhism is woven into Japan’s cultural fabric in ways that gives few wedges for Christianity to enter. This underpins Xavier’s frustration with Shinto Buddhism. It seems natural to Western Christians that the religion would spread with baseball, movies, fashion, and other aspects of Western culture. But Shinto Buddhism creates a fabric where Christianity isn’t needed. It encompasses Japanese culture and subconscious. In many regards, it is a part of Japanese identity even for those who are secular.

Japan’s Weird

Weird and strange are a matter of perspective. American culture is weird too. I would say it is weirder than Japanese culture. Strangeness extends beyond the typical targets of panty fetishes, game shows, vending machines, and other surface culture. A different perspective is far stranger and more welcome. Weird ideas may provide inspiration to solve a similar problem. It is strange how American culture relies on business for everything, including environmentalism. Edo period Japan’s approach makes more sense. It involved cooperation from all levels of society for the benefit of all. Some things are more important than short-term profit. Japan focuses on family, community, and social harmony. These three pillars are perhaps the weirdest things about Japanese culture to Western eyes. These ideas, perhaps, shouldn’t be so weird. After all, we too once had these pillars underneath Western society.

References

Baseel, Casey (2014) Why does Japan love fictional characters so much? Japan Today. http://www.japantoday.com/category/arts-culture/view/why-does-japan-love-fictional-characters-so-much.

Blair, Gavin (2014) Why Frozen was such a Big Box-Office Hit in Japan. Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/why-frozen-was-huge-japan-720193

Convention on Biological Diversity. Japan. https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/default.shtml?country=jp

Hoffman, M. (2014) Christian missionaries find Japan a tough nut to crack. The Japan Times. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/12/20/national/history/christian-missionaries-find-japan-tough-nut-crack/#.Vtrcrkf3x_k

Iwamoto, J. (2002) The Development of Japanese Forestry. UBC Press.

O’Shea, M. (2015). Karakuri: Subtle Trickery in Device Art and Robotics Demonstrations at Miraikan. Leonardo, (1), 40.

Yan, Hong Sen & Marco Ceccarelli. (2009) International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms. Springer Science & Business Media.

Always a pleasure reading your well-researched articles. I had a bit of The Matrix feeling though with the paragraph(s) concerning the Horyuji temple. Deja-vu-vu.

Thank you. I wanted to avoid the usual type of list.