“Pokémon episode 1 screenshot” by DVD of the first season. Licensed under Fair use of copyrighted material in the context of Pokémon, I Choose You! via Wikipedia –

Cartoons are usually seen as harmless entertainment for children. Other than the occasional kerfuffle over violence, most parents have no problems allowing their children to sit and watch the latest adventures of their favorite animated characters. The Pokemon cartoon was among the most popular animated children’s show of the 1990s. The show, which was based on the wildly successful video game series of the same name, followed the exploits of a Pokemon trainer named Ash Ketchum (in the American version) on his quest to become a Pokemon Master. Pokemon meant “pocket monster,” which described the titular creatures. They all exhibited unique characteristics, and would be trained in order to battle other Pokemon.

Most of the happenings in the Pokemon TV show were pretty benign, typical of many children’s shows of the day. But a dark mark on the record of an otherwise wildly successful franchise occurred December 16, 1997, when an episode of the children’s cartoon made its viewers ill.

Episode 38

The episode that aired at 6:30 pm on December 16 was called “Computer Warrior Porygon.” Millions of school aged children tuned in to watch Pikachu—a yellow rodent with electrical powers who is the flagship character of the franchise—and his trainer be transported inside of a computer, where they fought a Pokemon called Porygon. During the battle, Pikachu hit its opponent with an electrical attack that was depicted with a quick series of flashing lights.

The flashing attack sequence appeared on screen at 6:51 pm. By 7:30, 618 children had been rushed to hospitals. They suffered symptoms such as convulsions, altered levels of consciousness, headaches, breathlessness, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, and depression. Reports of the illness spread like a plague, to the point it warranted a report on the evening news. The news reports played the offending battle scene. After the evening news aired, still more children became ill.

The next day, TV Tokyo suspended Pokemon, promised an investigation, and issued an apology. Meanwhile, officers from the Atago Police Station questioned the shows producers on order of the National Police Agency. The Health and Welfare Ministry held an emergency meeting to try and figure out what happened. Video stores pulled any Pokemon videos from their shelves.

If officials were concerned, parents were downright panicked. Many slammed TV Tokyo with angry letters and phone calls, accusing them of putting ratings ahead of the health of their viewers. Some called for the TV station to install electric screening devices to block sequences like the one that caused the illnesses. How these were supposed to work, however, remains unclear.

Even the Prime Minister weighed in on the matter. He made a pretty bizarre statement about the dangers of rays and lasers, since they had been researched as weapons.

During the panic, Nintendo, the company behind the Pokemon juggernaut, saw its stock drop by five percent. However, the vast money machine that was the Pokemon franchise could not be laid low for long, and by April of 1998, the animated adventures of Ash and Pikachu returned to the small screen. TV Tokyo slapped warnings on every Pokemon episode from that point on. These warnings proved needless, because there has not been an incident similar to the December 16 outbreak since.

Bright flashes, epilepsy, and mass hysteria

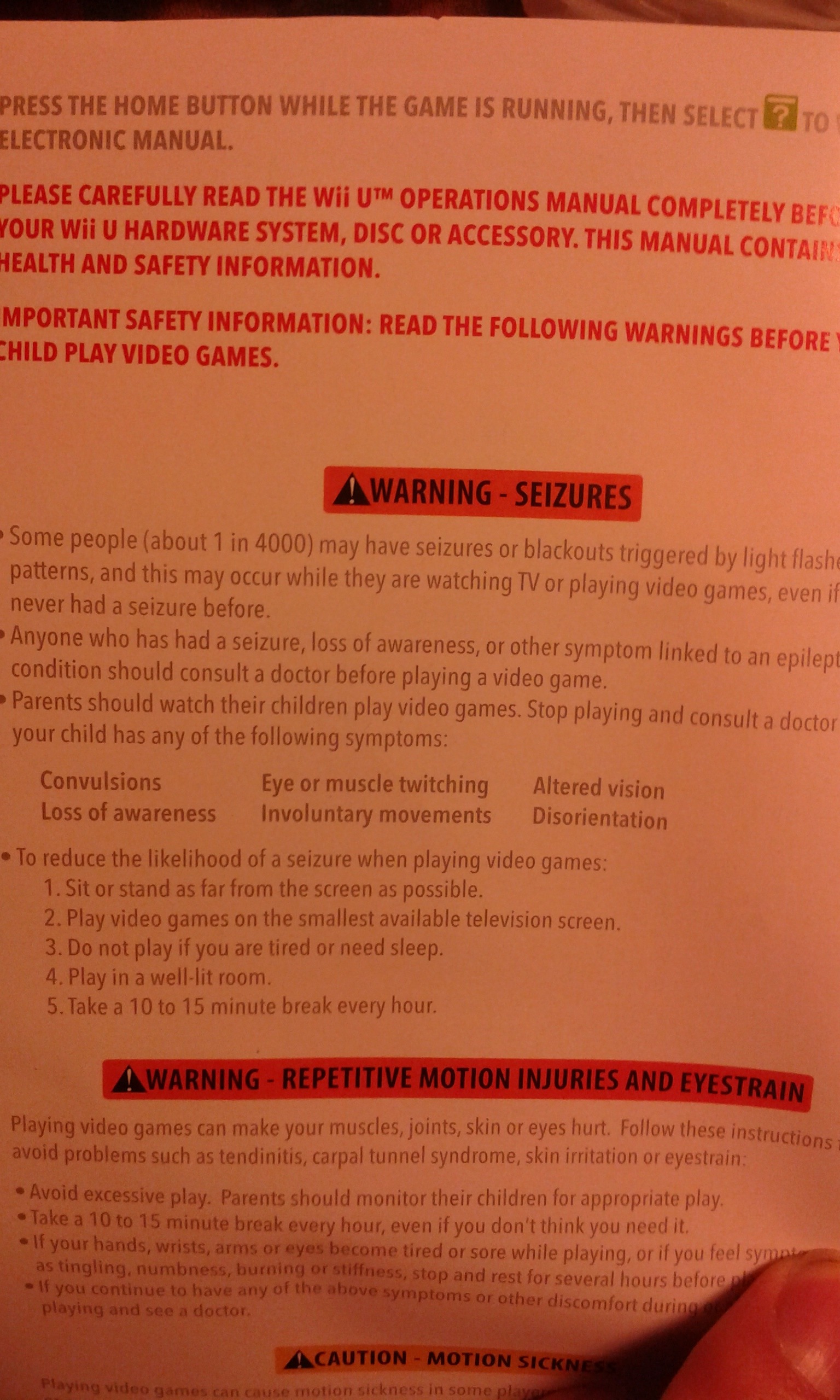

This was not the first time that Nintendo’s products were accused of causing harm to customers. The video game giant placed warning labels on its games after several teens experienced seizures while playing video games.

However, there is a difference between the flashes in the games and those on episode 38. Namely, the flashing technique, called paka-paka, had been used for years in anime, Japan’s distinctive style of cartoons, including in other episodes of Pokemon. In fact, episode 38 featured about the same amount of paka-paka as any other episode of the series.

It is not clear exactly how many victims suffered seizures in any case. In a survey conducted by Hayashi et all in the Yamaguchi prefecture, researchers found 12 victims had no history of epilepsy; of these 10 had seizures during the episode and 2 others fainted. The researchers concluded that 11 of the 12 surveyed showed signs of undiagnosed epilepsy.

Another survey, conducted by Yamashita et al, looked at children in 80 elementary schools in Fukuoka Prefecture. It was given six days after the outbreak. Teachers asked their students if they’d experienced symptoms, and questionnaires were sent to local medical facilities. Of 32,083 students surveyed, half the students saw the episode. One suffered convulsions during the outbreak while 1002 others reported minor symptoms. The questionnaires sent to the medical facilities showed 17 children treated for convulsions.

Yet another study conducted in the wake of the panic looked at four children affected by the outbreak. The researchers diagnosed them with photosensitive epilepsy, and believed that the rapid color changes were responsible for the symptoms.

It is clear that at least some of the children swept up in the panic really did suffer from seizures, in some cases because they suffered from photosensitive epilepsy. As to why this particular episode caused the seizures and previous ones did not, no one really knows. In any case, the children who suffered seizures were index cases, while the other children were afflicted by mass hysteria. They either observed others who suffered seizures, heard about the illness by word of mouth, or saw news reports. Seeing that others who had seen the episode had fallen ill made them believe that they were susceptible to the illness too, and that anxiety manifested as symptoms that were relatively minor and passed quickly.

These symptoms fit with those associated with mass hysteria: headaches, fainting, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, convulsions, and fainting. Some of these symptoms are commonly associated with seizures, though. These include nausea, convulsions, and seizures. However, other common seizure symptoms – such as drooling, stiffness, and tongue-biting– were not present in most victims. They only occurred in patients who were diagnosed later as actually suffering seizures.

The hysteria was primarily spread by the breathless media reports. While media in itself doesn’t cause mass hysteria, it does give it a route by which it can spread from a relatively isolated group to the larger community. Just as the newspaper in Mattoon helped spread the story of a fictional gasser and British newspapers spread the story of a razor-wielding madman dubbed the Halifax Slasher to other cities, the reporting on the Pokemon panic triggered a second wave of illness, especially because the nightly news foolishly replayed the scene believed to have sparked the outbreak to begin with. You have to wonder what they were thinking in playing a bit of video that they even suspected of being harmful, especially to children.

While mass hysteria explains most of the features of the strange Pokemon panic case, there are some questions that remain. There have been no cases like it before or since. Why would paka-paka, a commonly used technique in Japanese animation, cause outbreaks of photosensitive epilepsy in this particular case, when it never had before? With no other case data to go on, there is no real satisfactory answer. The Pokemon panic remains a strange and isolated case in the already bizarre annals of the history of mass hysteria.

Sources:

Bartholomew, Robert E. Little Green Men, Meowing Nuns, And Head-Hunting Panics: A Study of Mass Psychogenic Illness and Social Delusion. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2001. pgs 122-131.