The Season of Horrors

It may seem strange at first that summer is the prime time for ghost stories in Japan. We tend to associate summer with pleasant things… but imagine you’re living in early modern Japan.

You have no iced drinks, no electric fans, no convenient water taps. There’s basically no way to keep cool at night. So you lie awake, too hot to sleep, too hot to breathe, and listen to the buzzing of mosquitoes just outside the net around your futon. The next day you drag yourself to work again, through streets flaring with sunlight. It hurts your eyes and gives you a headache. Things go bad fast, and they smell. The next night brings no cool either, the air remains thick and stale and sticky like old sweat, and the mosquitoes are still buzzing… I wouldn‘t be surprised if I started seeing things after a while.

Also, if someone tells you a good ghost story and you get that shudder down the spine, wouldn’t that be refreshing at a time like this? It would possibly work as “a psychological form of air conditioning“.[i] Finally, in August you have O-Bon, the week-long festival of the Dead. So, a number of summer customs related to the scary and supernatural has arisen. For example, there is hyakumonogatari kaidankai, a meeting to tell one hundred ghost stories in a room with a hundred lighted candles. For every story told, the group extinguishes one candle, and when the last flame dies, it is said, a monster will appear.[ii] Also, the theatres and later cinemas of Japan traditionally offer horror stories in their summer programme, and that’s where O’iwa enters the picture.

The Birth of O’iwa

In 1755, the man who would later be known as playwright Tsuruya Nanboku IV was born in Edo as son of a dyer. Aged 25, he married the daughter of Tsuruya Nanboku III, but it took him another 20 years to write a successfull play. He then excelled at mixing well-known plots and settings with new elements, creating new types of characters and sharply observing the lives of the lower-class townspeople.[iii] His best-known work only premiered in 1825, four years before his death: Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan (The ghost-story of Yotsuya on the Tōkaidō (Eastern Sea Road)). Onoe Kigurorō III and Ichikawa Danjurō VII, two of the most famous actors of the day, played the lead roles.[iv]

The plot of Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan

The play is set in the same sekai (“world“: the historic situation and characters used) as Chūshingura, the story of the 47 rōnin, and was often staged alongside it. Iemon, a good-looking young samurai, has murdered the father of the woman he desired in order to be with her. However, his lord has to commit suicide (this is the Chūshingura plot) and Iemon loses his position.

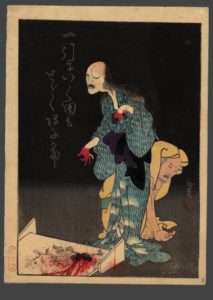

Forced to eke out a living as a paper umbrella maker, he grows tired of his sickly wife and child. Meanwhile, the daughter of a rich neighbor falls for Iemon. She sends a ‚medicine‘, actually a deadly poison, to O’iwa, so she could marry Iemon. But O’iwa survives, becoming horribly disfigured in the process. This prompts Iemon to leave her, and she dies, vowing revenge.[v] Iemon kills his thieving servant Kohei and nails the two corpses to a door which he throws into the river, to make it appear like a lover’s double suicide.

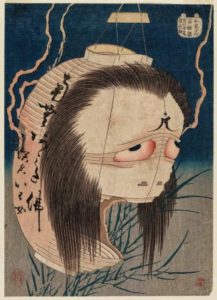

But O’iwa and Kohei return from their wet grave to haunt the murderer. They appear at Iemon’s wedding night, causing him to slay his bride and new father-in-law. Later, while fishing, he catches the very same door with the two corpses on it. The two ghosts keep appearing and accusing him, eventually driving him mad. In the last act, O’iwa breaks out of a burning paper lantern, an iconic scene often depicted in woodblock prints. Only when Iemon is finally slain, the ghosts are satisfied.

This story has been adapted and cited many times since then, in plays, prints, stories, movies, and anime. Even the ghost of Sadako in Ringu has some features of O’iwa.[vi] What made her scary then and still scary now?

The three horrors of O‘iwa.

Pollution

The female body itself is threatening to the patriarchal mindset. “Ancient worldviews frequently equated the female with the impure, often with evil itself. Given that her body was the site of

discharges and emissions, of miraculous change and transformations, she has been suspect of harboring all that is dangerous and threatening.“[vii] Childbirth and menstruation were stigmatized as polluting, which made women threatening to male ‘purity‘ – even outside the role of the seductress.

Mother and Monster

O’iwa has given birth shortly before the beginning of the second act and as such is affected by this pollution. The disfiguration of her face by the poison might be a visualisation of the disgust Iemon feels towards her. In addition, her last day is a bloody nightmare. As an effect of the poison, her hair falls out in bloody clumps. When Iemon tears the mosquito net out of her hands, he ripps off her fingernails. Finally, she dies by the sword. These events not only make her more and more polluted; they are also already part of her transformation into a monstrous ghost.

Remember, O‘iwa has just experienced all the transformations of pregnancy. Now her body transforms again, and in this state of in-between-ness, she dies. That may be one reason for her dangerousness as a ghost: “In most religions, the passage from one stage of life into the following one is seen as dangerous and demands support in the form of rites of passage. If such protective measures are lacking and a person dies during the transformation, this yields an enormous potential of threat for the community of the living.“[viii] O‘iwa dies in transformation. This makes her more powerful as a ghost, and thus scarier.

Rebellion

Class…

O’iwa is meek and obedient as long as she is ignorant of Iemon’s deeds. However, his betrayal of her ignites a fury so strong she returns again and again to haunt him. She is now in control, he is her victim: an inversion of the social order. As a kizewamono (‚naturalistic‘ play), Yotsuya Kaidan portrays the social problems and societal fears of its time. One of those is the decline of the feudal caste system and the fear of social unrest, when those who are meant to obey rebel against their „betters“ for being treated badly – as O’iwa does against Iemon.

Fourty years after Yotsuya Kaidan premiered, the samurai of Satsuma and Chōshū would rise against the Tokugawa government. Thus they ignited a civil war which led to the opening of Japan in the Meiji restoration of 1868. Yet, the seeds of this upheavel were already growing at the time of Yotsuya Kaidan. Enough perhaps to transfer the fear of power being turned upside down from a level of gender to a political level.

…and gender

Besides being potential political commentary, O’iwa shows the limits of a woman’s abilities to gain justice. “One of the chief ways in which women who have been trampled on become empowered is to turn into vengeful spirits after they have died.“[ix] She has to transform to become a monster and vengeful ghost, in order to gain power over Iemon. In life, she was at his mercy, caught within the confines of society and her role as woman and wife. She can only escape them through monstrosity and death.

At the same time, the woman exacting revenge on her deceitful, murderous husband is basically a conservative morality tale. In addition, it is not O’iwa but her sister’s fiancé, a male character, who actually kills Iemon. Thus in the end, societal norms and morals are reinforced, and the fear of social upheaval and female empowerment is banished.

Otherworldliness

One of the Japanese words for monster/spirit/uncanny being is bakemono or obake, literally „changing thing“. This allows the conclusion that transformation itself is a key element in Japanese concepts of horror, and especially ghost stories. When it comes to female ‚changing creaturues‘, „[i]n almost every instance, the mutation from benign, subservient female, into something ‚else‘/Other is motivated by a violent act of betrayal and murder“.[x] This exactly fits the situation of O’iwa, who transforms from obidient human wife into something terrible and Other. In her haunting of Iemon, she assumes a male position of power, another factor in the fear of rebellion and gender role reversal I discussed above.

An onryō…

But also, O‘iwa is the first woman in a line of revenging ghosts (onryō), who wreak havoc among the living for an injustice suffered before or in the manner of their deaths. As such, she has become so iconic that she overshadows her male predecessors such as Sugawara no Michizane (now deified as Tenman Tenjin, God of Learning) or the Taira warriors.[xi]

Carmen Blacker describes onryō as follows: “Most dangerous of all, however, are those ghosts whose death was violent, lonely or untoward. Men who died in battle or disgrace, who were murdered, or who met their end with rage or resentment in their hearts, will become at once onryô or angry spirits, who require for their appeasement measures a good deal stronger than the ordinary everyday obsequies.“[xii] A sudden or violent death, in contrast to a death of old age or disease, leaves the departed soul with some remaining energy. This is even more volatile if the soul harbours resentment, e.g. for their killer.[xiii] Nanboku cleary alludes to this type of ghost in his construction of O’iwa and her postmortal empowerment. She dies poisoned, betrayed, disfigured and furious – the ‘best‘ conditions to become an onryō.

… or another other scary creature?

However, male onryō usually caused disasters and plagues rather than appearing in human form to the object of their grudge. O’iwa‘s appearance refers to the classical shape of the female yūrei. (Long disshevelled hair, often white burial robes and the triangular headpiece assoicated with them, etc…).[xiv] In addition, she appears as corpse on the door, as a rat (her zodiac sign) or a lantern monster, further adding the category of yōkai/bakemono to her repertoire. The tangible person undergoes a series of painful transformations and turns into an unstable avanging ghost – ethereal in ist substance and mutable in its form. Woman, ghost, rat, lantern; onryō, yūrei, yōkai: O’iwa invokes the fear of all that is intangible and beyond our understanding.

The Burning Lantern

One of the features which brougth Kabuki ist popular appeal are keren, stage tricks which made stunning transformations of scenery and character possible in front of the live audience. Yotsuya Kaidan features a numer of keren, but one of the most iconic is chôchin nuke. In this scene in the drama’s last act, O’iwa appears in, or through, a burning paper lantern. For this, a slightly enlarged lanters is set aflame on stage, and the actor playing O’iwa emerges from it. He “slides through the burned-out aperture from behind the scenes, his timing in perfect accord with the man who does the burning”.[xv] As with other keren, finely tuned teamwork is essential to produce a credible illusion of the incredible and fantastic. In contrast, artists only needed colour and paper for their fantastic image.

Hokusai’s O’iwa

While a number of depictions of the chōchin nuke scene and other kabuki ghost scenes exist, Katsushika Hokusai’s (1760-1849) print is unique in that is is not a portrait of a specific actor. Ukiyo-e of kabuki characters were usually a kind of early modern movie poster, something you hung up on your wall because of the star actor you were a fan of, who was captured at the hight of his art in a striking pose. In contrast, Hokusai does not show an actor and his O’iwa does not emerge from the lantern. Instead, she is the lantern, and this completely changes the direction of the image.[xvi]

To this end, Hokusai merges the character of O’iwa with an only mildly scary yōkai, the chōchin obake or monster lantern. Chōchin obake are a subclass of tsukumogami (monsters born from objects wither discarded thoughtlesslly, or used for more than 100 years), ad are usually depicted with a mouthlike parting in the middle or lower, a rolling tongue and (usually) one eye. As such, they are more funny than threatening, but still good for a jump scare. Chōchin O’iwa, therefore, is an image full of allusions, some more playful, some rather scary.

Interestingly, O’iwa‘s depiction as monster lantern did not transform the category, as it did with onryō. Monster lanterns stayed the same, and the ‘monster lantern version‘ instead became a subordinate image for O’iwa.

Modern Representations: Ayakashi and beyond

I already mentioned the influce O’iwa has had on modern female ghosts such as Sadako.

Moreover, she appears in the anime Hōzuki no Reitetsu (2014) as the monster lantern. Even if she did not introduce herself, she is clearly recognizable by the eye swollen shut, the yūrei-style hair and generally non-comical features which set her apart from the usual chōchin obake. Most striking, however, I found the adaptation of Yotsuya Kaidan in anime form in Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales (2006), which features rats and doppelgangers and of cause the scene where O’iwa emerges from the lantern, and there’s nothing funny about that.

What made, and still makes, O’iwa scary, I think, are the feelings she evokes in us. Against her we are powerless, helpless, on many levels at once. Most of us have at some point done someone a wrong and can imagine Iemon’s guilt. We feel his fear, understand his flights, cover-ups and denials – all that while being aware what a despicable human being he is. In contrast, O’iwa in her onryō state is utterly alien. You can never be sure in what shape or manner she will appear next; it could be anyone, anything, anywhere. She destabilizes categories, perception and thus reality itself and drives you mad. And you cannot reason with her, reach her, or forcibly stop her. You are completely at her mercy, and she has none for you. What could be more horrifying?

Notes and References:

[i] Anderson & Ritchie, as quoted in Elisabeth Scherer: Spuk der Frauenseele. Weibliche Geister im japanischen Film und ihre kulturhistorischen Ursprünge. Bielefeld: transcript, 2011, 98.

[ii] If you like Japanese monsters as much as I do, check out the amazing website named for this event.

[iii] Shirane Haruo (ed): Early Modern Japanese Literature. An Anthology, 1600-1900. New York: Columbia UP., 2002, 844. See also http://www.kabuki21.com/nanboku4.php.

[iv] http://www.kabuki21.com/nakamuraza.php#jul1825

[v] The exact circumstances of her death vary between different summaries of the story. Sometimes she commits suicide, cutting her throat. Sometimes Iemon kills her, but in the only version I had access to, Mark Oshima’s translation of acts 2 and 3 for Shirane 2002, while grappling with Iemon over the objects (such as her bedding and mosquito net), he intends to sell in order to make her leave him, she accidentally falls into the Kohei’s sword, which had remained stuck in a pillar from an earlier fight.

[vi] An interesting article on this topic: Valerie Wee: „Patriarcy and the Horror of the Monstrous Feminine. A Comparative Study of Ringu and The Ring“. In: Feminist Media Studies 11 (2), 2011, 151–165.

[vii] Rebecca Copeland: „Mythical Bad Girls: The Corpse, the Crone, and the Snake.“ In: Laura Miller und Jan Bardsley (eds): Bad Girls of Japan. Houndmills, Balsingstoke, Hampshire, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, 14–31, 17-18.

[viii] Scherer 2011:50-51, my translation.

[ix] Samuel L. Leiter, as quoted in Richard J. Hand: „Aesthetics of Cruelty. Traditional Japanese Theatre and the Horror Film“. In: Jay McRoy (ed): Japanese Horror Cinema. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2005, S. 18–28, 24.

[x] Wee 2011:154.

[xi] For a definition of onryō, see http://yokai.com/onryou/, where you can also find an article about Michizane. For a story about Taira-clan onryō, see https://hyakumonogatari.com/2013/10/07/heike-ichizoku-no-onryo-the-vengeful-ghosts-of-the-heike-clan/

[xii] Carmen Blacker: The Catalpa Bow. A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan. London: Allen & Unwin, 1975, 48.

[xiii] Scherer 2011:40-41

[xiv] For a first look, see http://yokai.com/yuurei/. There are whole books on the different types of yūrei… This one, for instance.

[xv] Samuel L. Leiter: „Keren. Spectacle and Trickery in Kabuki Acting“. In: Educational Theatre Journal 28 (2), 1976, S. 173–188, 188.

[xvi] Scherer 2011:112, 114.