The Japanese fascination with robots might seem strange to outsiders. After all, an entire genre of manga and anime is devoted to giant robots slugging it out (a genre that, for some reason, also likes to make weird Jungian segues into madness.) Additionally, Japan leads the world in the field of robotics.

A brief look at Japanese history shows that this fascination is not anything new. Rooted in ancient Chinese clockwork mechanisms imported via Korea, traditional clockwork puppets–the Karakuri Ningyo– have a long history in Japan.

Ritual puppets

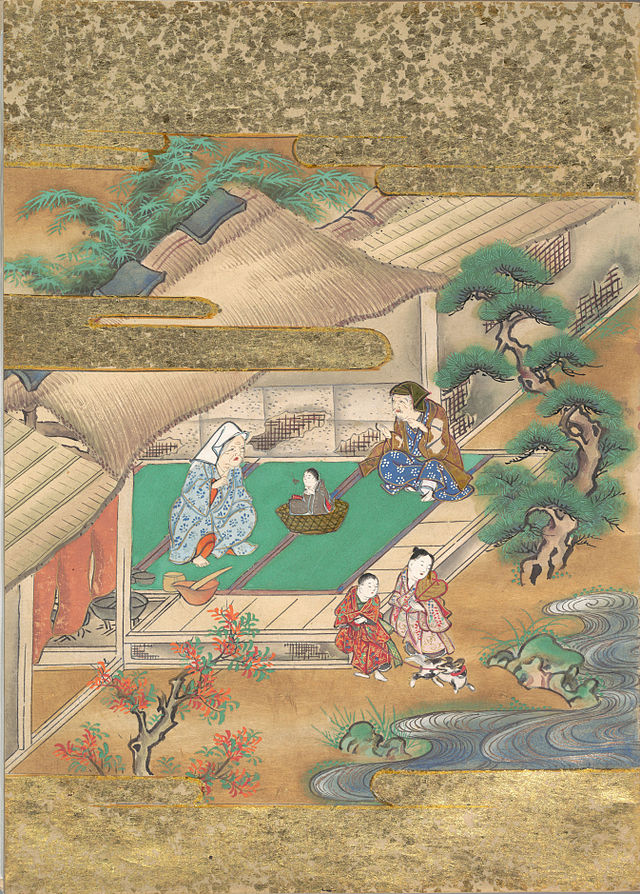

Karakuri Ningyo could serve several functions in ancient Japanese society. Perhaps the oldest was their use in ritual festivals. Puppets had long served an important role in Japanese ritual life. Puppet shows were often used to tell stories of gods, goddesses, and spirits. They personified the overlapping and somewhat contradictory worlds of the human and sacred. These ritual puppet performances were performed before the New Year or the onset of a new season, to call down rain, or to drive of pests and disease. All members of society enjoyed these puppet plays, from the Emperor on down.

With the importance of these puppets in festivals, it shouldn’t be much of a surprise then that when the clockwork technology made its way to Japan, they would incorporate it into their mystical puppet plays. The clockwork would give the puppets an almost magical quality, allowing them to move on their own.

Ritual puppets were featured heavily in festivals held all over Japan. They were built into triple-decker Dashi floats. These floats were huge constructions that required 20 men to pull, and while they did not always sport Karakuri many would. The top stage of Dashi Karakuri would feature up to three puppets performing scenes taken straight from traditional mythology and folklore.

Towns would compete to produce the best Dashi floats. The festivals would be a chance not only to socialize, but to show off pride in a town or village by displaying their Dashi floats.

Puppet plays

While the earliest uses of Karakuri were for religious festivals, the clockwork puppets were also used to perform plays strictly for entertainment, although of course many of these plays had their origins in mythology and legend. It is interesting to note that many plays, especially during the Edo period, were written specifically to be performed by puppets. Noh, Kabuki, and Bunraku theater were heavily influenced by the puppet theater, and often imitated the puppet shows directly. These forms of theater focused more heavily on gesture and movement than the use of language. This, perhaps, influenced the strange sets of hand gestures and poses often seen in anime and Japanese television.

These Karakuri plays became famous after Takeda Omi, a clock maker, put on the first Karakuri play at Dotonbori, in Osaka, in 1662. Plays were performed in the theater for the next 110 years. In 1758, the plays were so popular that the theater ran 27 shows a day.

Domestic Automatons

Perhaps the most famous Karakuri were the Zashiki Karakuri, which were small, domestic clockwork servants. Basically, they were the Edo period’s equivalent of the Roomba. Their mechanisms were far more complex than those used in the plays, and were often built using Western clockwork mechanisms. They could even be steam powered.

The most famous of the Zashiki Karakuri were “Chahakobi Ningyo,” the tea-serving dolls. A host could place a teacup on the tea tray the doll held. So loaded, the doll would roll over to the guest, and stop when the guest took the teacup. When the guest put the cup back on the tray, it would return to the host. The doll would move its feet and nod its head as it moved. The design even included a mechanism by which the host could set the distance the robot could move, giving the illusion that the robot could “see.” The piece was used mainly for entertainment, and was only available to the richest aristocrats.

Another interesting bit of mechanical wizardry from the period was the “Yumihiki Doji,” the archer doll. The doll can pick up an arrow and fire it at a target, which it would hit nine times out of ten. Amazing considering it was “programmed” only using gears.

Sources:

Boyle, Kirsty. “Butai Karakuri.” Karakuri.info. January 14, 2008. Accessed November 1, 2014. http://www.karakuri.info/butai/index.html

Boyle, Kirsty. “Dashi Karakuri.” January 14, 2008. Accessed November 1, 2014. http://www.karakuri.info/dashi/index.html

Boyle, Kirsty. “Karakuri Origins.” January 14, 2008. Accessed November 1, 2014. http://www.karakuri.info/origins/index.html

Boyle, Kirsty. “Zashiki Karakuri.” January 14, 2008. Accessed November 1, 2014. http://www.karakuri.info/zashiki/index.html

Is there any way you could shoot me an email, Trying to figure out your souces for the Jorogumo and they are not posted. Thank you.

That article was before we started our formal citation policy. I did a little digging to find a few of Andrew’s sources and added a few of my own that support the article. I added the sources to the article. I will also email you the citations.