Japan’s turbulent history was marked by a series of internal wars among various noble factions, vying for the title of Shogun. While most of its history was spent fighting itself, the greatest threat to Japan came from outside, in the guise of Kublai Khan. Grandson of the infamous Ghengis Khan, Kublai succeeded to the throne of the Mongol Empire in 1260. He focused the wrath of the Mongol hordes against the Sung dynasty in China, using a combination of Mongol warriors and Chinese defectors to turn the tide against Sung defenders.

Even as Kublai Khan was wreaking havoc across China, he turned his eyes to Japan. The Japanese had long been trade partners with the Sung dynasty, and this financial support was vital to continued resistance in China. Kublai Khan sent envoys to the Japanese in 1266 and 1268, demanding them to become part of the Mongol Empire and to cut all trade ties to the Sung. The Shogunate rebuffed the Mongol offer and summarily executed the Khan’s representatives.

Kublai Khan could not let this insult go unpunished. The fury of the Great Khan was aimed squarely at Japan.

The First Divine Wind

Kublai ordered his vassals in Korea to construct a great fleet to punish Japan for its insolence. Some 900 ships strong, the fleet would transport 23,000 Chinese and Mongol soldiers and 7,000 Korean sailors.

The force set sail on October 3, 1274, only 120 miles of the Korea Strait between them and the Japanese home islands. Their first target was the island of Tsushima, situated in the middle of the strait. Its tiny garrison was easily overwhelmed. The garrison at the island of Iki, closer to the main islands, was also soon overwhelmed. By October 14, the fleet attacked the port of Hirado, positioning itself to launch the invasion of the main island.

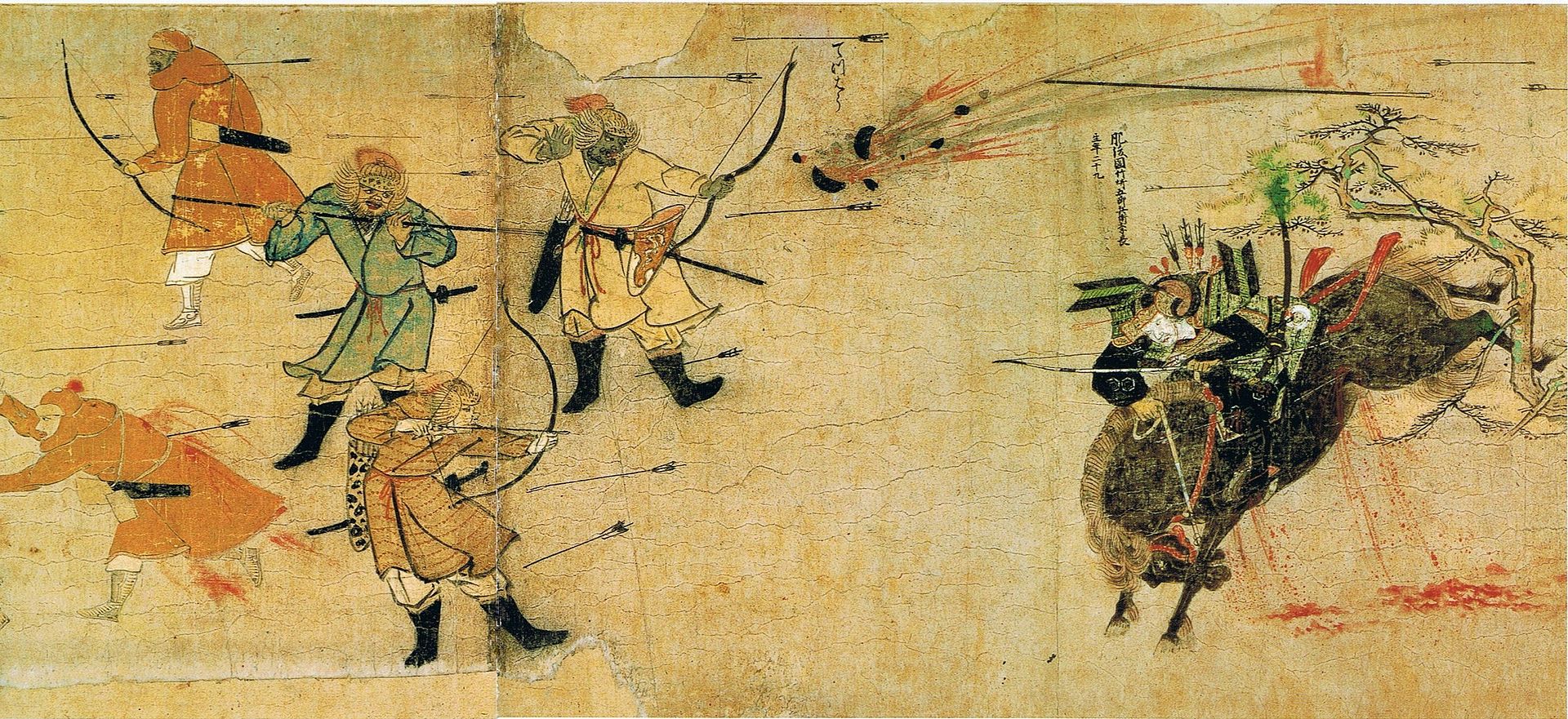

Spies among the Koreans had warned the Japanese that the attack would come at Hakata Bay. Samurai and their retainers rushed to the area, some 6,000 forming up in a hastily assembled army, ready to fend off the foreign invaders. It wasn’t long before the samurai and the Mongol invaders clashed on the battlefield, and their differing approaches to warfare soon became apparent. The samurai, motivated to seek honor, attempted to instigate individual duels, while the Mongol and Chinese forces fought as a unit.

Even so, the samurai fought well, despite being hugely outnumbered. Over the course of a week, the invaders pushed them back from the beaches of Hakata Bay. By the 20th, the Japanese were forced to abandon their position and retreat 10 miles to an abandoned fortress at Mizuki.

The wounded Japanese gathered their strength at the ancient castle, with reinforcements pouring in from the countryside. Meanwhile, the Khan’s army failed to press its advantage. Perhaps they feared a Japanese ambush if they pressed further inland. They certainly feared the weather, which was deteriorating quickly. Korean sailors, familiar with the fickle nature of weather on the Korean Strait, believed a typhoon was on the way. The Great Khan’s fleet would be helpless moored in the rocky waters of Hakata Bay.

Mongol leaders then decided to withdrawal, but they were too late. The storm struck, scattering the mighty fleet and grounding some 50 ships. Samurai promptly boarded the stricken ships and killed anyone they found on board.

Kublai Khan’s invasion was defeated, but barely. In fact, the aborted invasion was a success, as it succeeded in its objective to cut Japanese trade with the Sung. For its part, the Shogunate was made painfully aware of how woefully unprepared it was to stand toe to toe with the world’s largest empire. Knowing that the Khan would not forgive or forget, Japan’s leaders prepared for a second invasion of the homeland. They ordered a 5-9 foot stone wall built along the 25 mile stretch of the bay, set back 150 feet from the beach. Locals were levied to serve on the wall, while fishing boats and their crews were forced into service as an ad hoc navy.

The Second Divine Wind

Meanwhile, the Khan consolidated his hold on China. He sent envoys to Japan again in 1275. The Shogunate had them executed. Four years later, as the Khan finished off the last of the Sung resistance, he sent still more representatives. These were summarily executed on the beach at Hakata Bay, before even meeting the Shogun.

Furious at the insult, Kublai Khan ordered two massive fleets assembled. The first consisted of 900 ships, manned by 40,000 Mongol and Korean warriors and 17,000 sailors. This was dubbed the Koryo Eastern Route Division. The second, the Chinese Chiang-Non Division, consisted of 3,500 ships and 100,000 Chinese soldiers. The world would never seen another sea borne invasion force this large again until World War II.

The Eastern Route Division struck out for Japan on May 3, 1281. They took Iki within a week. The original plan was for both divisions to meet at Iki and strike Hakata Bay as one. But Eastern Route commanders grew impatient, and by mid-June decided to attempt an assault on their own. However, the defensive wall did its work well, and the Japanese defenders shoved the Mongols back into the sea.

The bloodied invaders withdrew to Shika Island. Their pain did not end when they took to the sea. Japan’s re-purposed fishing and trade ships proved to be apt raiding vessels, and the samurai’s skill at close quarters combat proved deadly among the confines of a ship. So harassed, the Mongols were forced to withdraw back to Iki, with their Japanese pursuers not far behind.

When the Chinese Division finally arrived, they combined with the bloodied Eastern Route Division at Hirado. The combined force made for Imari Bay, 30 miles south of Hakata, hoping to bypass the formidable defenses at Hakata. The Japanese were waiting. The forces met on the beach, beginning a two-week long battle. While the land forces fought, the sailors chained their ships together to form a floating fortress. The Japanese coastal navy could do little against the massive armada. Meanwhile, both sides suffered mounting losses in the hard fighting ashore.

At this point, legend and history meet. The Mongols were preparing to launch their final offensive against the vastly outnumbered Japanese. The situation looked impossible. Emperor Kameyama, descendent of the goddess Amaterasu according to legend, pleaded with his divine ancestors to save his people from destruction.

On July 30, they answered. A typhoon struck the gathered Mongol ships with hellish fury. The invading armada, moored together as it was to defend against attack, was unable to maneuver in the gale force winds and massive waves. Ships slammed into each other as they tried to escape the narrow bay, sinking into the restless waters with their crews trapped aboard. Only the lightest, most maneuverable craft were able to escape the natural massacre. Japanese legend claims that some 4,000 ships sank that day, drowning approximately 100,000 men. Those who survived and washed ashore were executed. The bay entrance, it was said, was so clogged with debris that “a person could walk across from one point of land to another on a mass of wreckage.”

Even if the extent of the devastation was exaggerated by the Japanese, it was enough to drive back the invaders for good. The defeat was so stunning that Kublai Khan could not muster support for a third invasion.

The Third Divine Wind

The second kamikaze, and the first to be called a “divine wind,” marked a change in how the Japanese saw themselves. The storm could only have been the act of a divine hand reaching from the heavens to influence the affairs of man. The Japanese began to see their islands, and thus themselves, as favored by the gods. This belief in Japanese exceptionalism would later fuel Japanese isolationism and, in the 20th century, the extreme nationalism the characterized Japan during World War II.

This extreme nationalism depended on co-opting history and culture to serve the ends of a fascist regime. When Japan found itself on the defensive in World War II, the leadership hearkened back to the storms of the 13th century that saved the homeland from foreign invaders. But, as with everything touched by their nationalistic fervor, they took a formative event in the Japanese national identity and twisted it to their own ends. The “divine wind” that would save the Japanese from the Allied invaders would not come in the form of a well-timed typhoon, but as young men willing to die for their family and country.

The concept was advanced by Vice Admiral Onishi Takijiro, who recognized by the latter part of the war that the Japanese Air Force could no longer compete with the technologically and numerically superior Americans. So, he proposed using planes as manned missiles, the advantage being that the pilots of the suicide planes would be easy to train. They’d only need to learn how to take off, not land. The Vice Admiral believed that the suicide bombers would terrify the Allies and boost morale among the Japanese populace.

Oddly enough, the Japanese were not the originators of the term kamikaze as suicide pilots. The pilots were dubbed Shinpu. It was American translators who saw the characters forming the word as being an allusion to the nation-saving storms of the past. This slip in interpretation eventually got back to the Japanese, who adopted it as their own.

The third divine wind damaged or sunk 300 US ships and was responsible for some 15,000 US casualties. Thousands of Japanese died executing suicide attacks. Thousands more were ready to die, should Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan, be executed.

In many ways, the third divine wind not only failed to drive away the American invaders, but it helped hasten the Japanese defeat. Qualified pilots died by the hundreds during the program, not to mention the destruction of precious planes. Also, the kamikaze attacks hardened American resolve to defeat the hated Japanese. Finally, the kamikaze attacks factored into Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrendered. No divine wind, man-made or otherwise, could save Japan from bearing “the unbearable” burden of defeat.

Sources:

Clements, Jonathan. “A Brief History of the Samurai: A New History of the Warrior Elite.” Constable & Robinson, Ltd. 2010. pgs 302-303.

Delgado, James P. “Kublai Khan vs. Kamikaze.” Military History. July 2011. Vol 28 Issue 2. p.58.

“The Kamikaze Threat.” pbs.org. 2003. Public Broadcasting System. October 25, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/perilousfight/psychology/the_kamikaze_threat/

Lannom, Gloria W. “Beware the Kamikaze.” Calliope. March 2012. Vol. 22. Issue 6. p.15-17.

What about Typhoon Cobra and Typhoon Viper? Shouldn’t they also be mentioned as Divine Winds which would have decimated a less formidable force than that of the Allied Navys about to invade Japan?

You make a good point. I suspect the typhoons you mention were too similar to storms that struck the Japanese fleets just a few years before. Typhoon Cobra and Viper would meet the same criteria as the storms that hit the Mongol fleets, however. It has more to do with mythologizing. If the US had hit a stalemate against Japan because of the typhoons, it’s possible they would’ve gained the same divine moniker as the Mongol-destroying storms.

Wind in written history, quite a subject to be delved into.

Thank you for a great researched article . Yours was the only I`ve found so far with any historical

content. My studies will continue in men and wind. Kenro

I’m glad you found the article helpful!

Since the characters for kamikaze are 神風 (kanji which would be individually read as kami-kaze; hence the American interpretation), I believe the Japanese term must be spelled ‘Shinpuu’ and not ‘shinpu’, as ‘shin’ and ‘fuu’ are the onyomi readings of the characters.

Great post, by the way! 😀

Thanks for clarifying! Kun’yomi and On’Yomi readings can be a bit confusing as for when they are used. Of course, I’ve seen academic articles from scholars on Japanese history use different transliterations.