JAXA, or The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, formed in 2003 with the mergers of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, the National Aerospace Laboratory, and the National Space Development Agency of Japan. The new agency began with the launch of several observational satellites and the ambitious Hayabusa mission. Hayabusa’s goal was to study Itokawa, a potato-shaped asteroid measuring 1,800 feet by 1,017 feet by 900 feet and to test various new technologies, such as a new ion propulsion module (Yeomans, 2006). The asteroid was named after engineer Hideo Itokawa.

As JAXA’s first major mission, Hayabusa was seen as proof of the new agency’s abilities. As McNicol wrote for Discover (2006):

“It’s been bust and boom for Japan’s Hayabusa spacecraft, intended to establish the country as a serious player in space exploration.”

The craft was to orbit the asteroid and touch down to collect a sample before jetting back to earth. Once the craft reached the asteroid, problems began. First, the asteroid was more rocky and unsuitable for touchdown than previously thought. A thruster developed a fuel leak, causing the craft to tumble and sever its connection with Earth for a time. Radio signals took 16 minutes to reach the craft, adding to the difficulties. When the craft did touch the asteroid, the mission team was unable to determine if a sample had been collected (Yeomans, 2006).

Fortunately, the mission team managed to overcome the difficulties of the collection and the samples returned to Earth in 2010. Space missions take a long time!

JAXA continued with other supersonic flight tests, observation satellites, and other Earth-area missions. JAXA worked with NASA to send astronauts into space aboard the Space Shuttles up until NASA retired them (JAXA, n.d.). Japanese astronauts also served on the International Space Station.

JAXA has sent probes toward other planets, such as Akatsuki, which entered into the orbit of Venus in 2015.

Japanese Women in Space

Chiaki Mukai was the first Japanese woman to travel into space. She traveled aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1994, and returned to space aboard Discovery in 1998.

Naoko Yamazaki was the second Japanese woman to travel into space aboard Discovery in 2010 (No space, 2017). She served as the arm operator for the Discovery and for the ISS. Naoko was a mother, and took her daughter with her to the US during her training. Her husband quit his job at one point to stay at home with their daughter. This stands out because Japan remains a country with a large gender imbalance. Gender roles remain traditional: husbands work outside the home, wives work in the home. These traditional expectations contribute to the declining birthrate in Japan, but let’s save that for another article. In any case, Naoko retired from JAXA and went to the Japanese Cabinet Office’s Space Policy Committee with a goal (among many!) of shifting education and the agency toward encouraging more women to enter astronomy (No space, 2017).

JAXA Collaboration

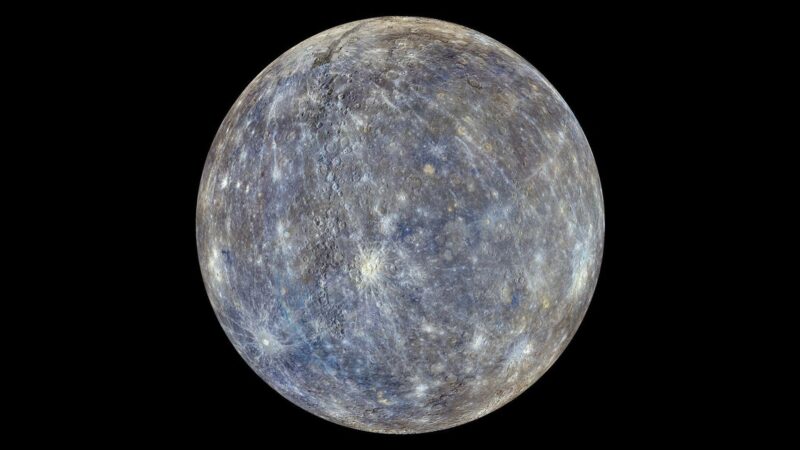

JAXA doesn’t only collaborate with NASA. The agency also works with ESA, the European Space Agency. All three agencies often work together on missions, such as International X-ray Observatory, which aimed to study high-energy space and continue where the Chandra X-ray Observatory left off (Kruesi, 2014). JAXA and ESA launched a joint-mission aimed at studying Mercury in 2018. The craft, named, BepiColombo should begin orbiting Mercury in 2025.

Space is Hard

Space is hard, and that’s quite an understatement. JAXA’s feats shouldn’t be compared with what NASA does. Both agencies work together and have different mission priorities. New Horizons, for example, traveled all the way to Pluto in 9 years. Whereas, the ESA and JAXA mission to Mercury will take 7 years. Mercury sits at 77 million kilometers from Earth; Pluto sits 5.05 billion kilometers. It seems the ESA and JAXA is more “primitive” than NASA, but the missions differ. New Horizons is a flyby; the Mercury mission is an orbiting mission that deals with the heat of the sun.

JAXA’s Hayabusa missions touched down on asteroids and, in the case of Hayabusa 1, return with samples. That is an impressive feat!

Space Matters

Many people consider space technology and research a waste of money. They forget that the smartphone in their pocket, their big-screen TV, their wireless American football broadcast, all came from space research. Space spending yields dividends that cascade down in unseen ways: clothing materials, consumer electronics, entertainment, and even food. JAXA, NASA, ESA, and even Russia’s space agency deserves far more funding because of the technological benefits everyone gains from their research.

Space offers the only way for perpetual economic growth. Earth as finite resources. Outside of entertainment, software, and other intellectual areas there’s a hard limit to economic growth because of the finite nature of Earth. Space, however, offers near-infinite resources. There’s entire planets made of methane; there’s asteroids loaded with gold and rare-on-Earth metals (Steigerwald, 2017):

“However, there are a fair amount of trace elements that are economically valuable like gold, platinum and rhodium,” said Lauretta. “A small, 10-meter (yard) S-type asteroid contains about 1,433,000 pounds (650,000 kg) of metal, with about 110 pounds (50 kg) in the form of rare metals like platinum and gold,” said Lauretta.

Larger asteroids offer more metals. The trick is decreasing the cost of getting into space so mining these resources become more viable. And that requires research. The work these space agencies do pioneers the future. JAXA faces many problems with the state of Japan’s economy and decreasing population, but JAXA remains one of the most important agencies for the technological and economic future of Japan.

References

JAXA History. (n.d.) JAXA https://global.jaxa.jp/about/history/index.html

Kruesi, L. (2014). Has NASA, lost its edge? Astronomy, 42(9), 32–37.

McNicol, T. (2006). Japan Stakes Its Claim in Space. Discover, 27(2), 12.

No space for young women (2017). The South Asian Post.

Steigerwald, William (updated 2017) New NASA Mission to Help Us Learn How to Mine Asteroids. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/content/goddard/new-nasa-mission-to-help-us-learn-how-to-mine-asteroids

Yeomans, D. (2006). Japan visits an asteroid. (Cover story). Astronomy, 34(3), 32–35.