Japanese professional wrestling has roots in American pro-wrestling. Many of the holds and brawling seen in early matches came from the various styles popular in the United States. The origins of Japanese pro-wrestling traces to Rikidozan, a former sumo wrestler who switched to it in 1951. Two of the most important wrestlers trained under him. Antonio Inoki and Shohei Baba. Although Inoki and Baba wrestled as a tag team, they had different approaches and ideas about pro-wrestling. They each founded their own company so they could focus on their vision of what pro-wrestling could be. Baba founded All Japan Pro Wrestling, AJPW for short, in 1972, after Rikidozan’s death (Lindsay, 2016).

Baba saw AJPW as a means to showcase what came to be called King’s Road Style and even managed to invite American wrestlers like Terry Funk to work for the company (Lindsay, 2016). Unlike what we know about professional wrestling–the exaggerated costumes and personalities and bombastic dialogue–King’s Road focused on physical storytelling. Most of the tension and drama happened in the ring. Of course, everything was planned. Pro-wrestling is, after all, a planned competition that tells a drama. In many regards, pro-wrestling is similar to opera with the character melodrama and spectacle. Baba planned matches and wrestler career arcs months and years in advance (Lindsey, 2016). This allowed him to build a story around a wrestler as he struggled up the ranks of the company. In his booking, wins and losses mattered for wrestlers. Newcomers could move up the ranks with rare and hard-won victories against veterans, all to the delight of the crowd.

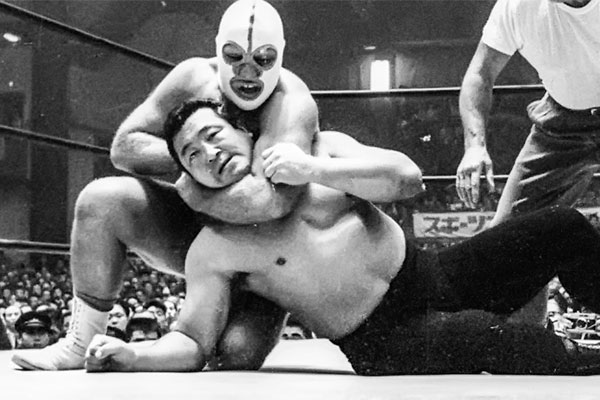

Baba and the wrestlers focused on massaging the crowd with the logical way matches flowed. Matches began tentatively with wrestlers trying to feel out each other’s strengths and weaknesses with strikes and other light moves. Then they would attack the weakness (such as a leg) with various moves while the other did his best to reverse and attack. This would continue until one developed enough “fighting spirit” to do his finisher and win the match (Lindsay, 2016; History, 2018).

This match drama even extends to the wrestlers. As a rookie wrestler faces off more often against a veteran, he becomes more resistant to the veteran’s moves. For example, in their first fight, the rookie is put away with a single finisher from the veteran. The next time might take 2 finishers. The third time might turn the finisher into just another move, until the veteran has to use his strongest attack (Lindsay, 2016; History, 2018). As you can tell, action anime tends to structure itself after King’s Road.

The AJPW liked to use the formula of an indomitable Japanese wrestler eventually winning against the larger and stronger gaijin wrestler. But this formula had to change as the American wrestlers became familiar to fans, and when in 1989 the WWF, the World Wresting Federation (now the WWE, World Wrestling Entertainment), dominated the wrestling scene in the US. But relying on native wrestlers for the narrative helped point the company toward its golden age.

In 1990, AJPW lost many veteran wrestlers to another company, but this allowed for a change that benefited the company. Four young wrestlers, known as the Four Pillars of Heaven by fans, stole the show. Their names were Misawa, Taue, Kawada, and Kobashi. They brought excitement for the fans and developed the King’s Road Style further. New wrestlers had to fight their way up the ranks until they could challenge the “Elite Four” themselves. Remember how the wrestlers built up resistance to special moves in the match narrative? This was designed to maximize the emotional payoff for the fans of each wrestler. So when an up-in-comer challenged one of the Elite Four, the fans revel even when their favorite up-comer is defeated. If one of the Elite Four has to resort to his strongest finisher to win, the up-comer basically won to his fans. The up-comer gained a lot of respect for forcing such a strong move. Any wrestler that survives three finishers and still gets up was seen as a force to be respected (Lindsay, 2016).

Let me take a moment here to point out what you are likely seeing. Pokemon seems to structure itself after King’s Road Style during its heyday. You are an up-in-coming trainer who has to fight her way up the ranks until she becomes strong enough to face the Elite Four. Matches in Pokemon also follow King’s Road Style (at least if you are playing the game without any foreknowledge). You have to feel out the weaknesses and strengths of your opponent before using your finishing attacks. Each opponent also has a specialty, like in King’s Road. Action anime often follows this method too. The protagonist will be defeated several times by this main rival, becoming a little more resistant and stronger each time. Eventually, he has enough “fighting spirit” to win. Ichigo verses Ulquiorra is a good example.

Many fans lost interest in the slower pace of King’s Road, against the fast spectacle of Strong Style and American styles. But the influence of the style remained in the pro wresting world and within video games and anime.

Pro wrestling has gained popularity lately on the Internet. In 2012, Bushiroad, an entertainment company known for its trading cards and anime characters, bought New Japan Pro Wrestling (the company Baba’s tag team partner founded). With the increase in overseas interest in anime and all things Japan, they started pushing NJPW online (Nakamichi, 2019):

“Pro-wrestling, card games and animation — they were all seen as subculture 20 years ago, but they’ve since grown into a mainstream culture,” Bushiroad’s Chief Executive Officer Yoshitaka Hashimoto said.

According to Nakamachi (2019), 4 in 10 NJPW fans are women, compared to a male dominated audience a generation ago. The increase in diversity reflects an increase in interest in a physical means of telling a story. While it isn’t as popular as Strong Style (as represented by NJPW), King’s Road has a chance to flourish with the increasing interest in pro wrestling.

References

History of King’s Road Style. YouTube: Dave Knows Wrestling. Posted December 26, 2018. Accessed May 17, 2020. https://youtu.be/k2FpNXx1dyM

Lindsay, Mat (2016) King’s Road: The Rise and Fall of All Japan Pro Wrestling. Vulturehound. https://vulturehound.co.uk/2016/08/kings-road-the-rise-and-fall-of-all-japan-pro-wrestling-part-1

Nakamichi, Takashi, and others (2019) Japan’s Next Cultural Export After Anime Might Be Pro-Wrestling. Bloomberg: Business Source Premier.