Income inequality has become a common concern. Income inequality is the gap in income different segments of a population. Economists argue about how much, or even if, income inequality helps or damages an economy. Some inequality is healthy for an economy. Social status drives some people to found businesses and work harder, both with rippling effects across the economy. Money also attracts itself. Capital, physical and financial assets that generate money, attract money. Those who own capital will have higher incomes than those who do not.

Some economists believe raising taxes on higher-income people damages economic growth, delaying the development of capital. This capital helps workers be more productive, which also increases wages (Henderson, 2020). However, other economists worry the accumulation of wealth to an increasingly smaller segment of society damages the economy. It limits spending. Middle-and-low income spending, because it is a the largest portion of a population, would provide more sustainable growth if the wealth of capital funneled to them in great proportion (Rugaber, 2013). Greater access to income among these income levels would also allow for more small businesses to develop.

These academic arguments often simplify to whether or not wealth should be redistributed by the government or by other means. Other factors play a role, however. Let’s look at Japan and compare it to the US.

Japan’s economic system seeks to balance growth and income distribution to create socioeconomic stability. In other words, Japan wants to avoid high income inequality while retaining just enough to simulate growth. Median net wealth (a family’s assets, such as a home and savings, minus debt) in Japan stands at $104,000. Compare that to the US at $62,000. The average Japanese family is 40% richer than the average American family (Koll, 2020). This trend applies to the lowest income level too: 5.5% of Japanese people own less than $10,000 in assets. In the US, 28.4% of people own less than $10,000. However, the US has two times the number of millionaires (Koll, 2020).

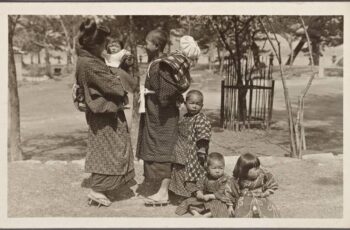

This variation comes, in part, because of Japan’s small labor pool. Small labor pools increase competition among employers for workers, raising their wages. But Japan also has a history of high-income tax rates. In 2015, high-income taxes stood at 45% with inheritance taxes at 55% (Koike, 2015). Japan also has a life-time employment system where companies (Huang, 2020):

- Promise to take care of employees until retirement.

- Wages are determined by seniority.

- Allow labor unions.

This system prevents wide gaps between executive managers and the rest of the company’s workers, divided by seniority. However, it also hurts young workers who are paid lower wages despite higher productivity. Companies are moving away from this system in favor of part-time work (Huang, 2020). Koike (2015) explains that Japanese culture remains sensitive to inequality, driving the richest people to avoid displays of wealth and to not publicly complain about high tax rates:

We Japanese have a deeply ingrained stoicism, reflecting the Confucian notion that people do not lament poverty when others lament it equally. This willingness to accept a situation, however bad, as long as it affects everyone equally is what enabled Japan to endure two decades of deflation, without a public outcry over the authorities’ repeated failure to redress it.

On a global level, income inequality is slowly declining. Inequality is measured using the Gini coefficient: 100 = one person gets all income, 0 = complete equality. Between 2003 and 2013, the coefficient fell from 69 to 65 (Henderson, 2020).

As you can see, income inequality is more complex than the usual socialist vs capitalist arguments. It’s impacted by more than taxes: culture, labor market, consumption trends, and many other factors. For example, if more people would spend less and invest/save more, over time inequality would fall. Likewise if more jobs are created than workers to fill them, incomes would increase.

Commentary

Economics is fascinating in its complexity. Behind all of it is human psychology. Complete equality isn’t possible in large societies; it appears possible in small, tribal societies, however. Humans consume based on social status desires and other motives. Inequality is a driver for growth, but within limits. I side with the economists who believe too much is a detriment. Providing wider access to otherwise locked-up wealth would allow more people to create businesses and also widen spending. Of course, over time this wider spending would pool toward those with capital. Money attracts itself over time. However, governmental redistribution runs into a variety of problems. Corruption would be one example. After all, who would get the funds? Rather, a cultural shift toward saving and investing along with pro-small business laws would empower people along the low-and-middle income levels. Perhaps even a universal minimal income to everyone in a certain tax bracket would also help. Such a system would encourage some free-loaders not to work, but it would also allow lower-income entrepreneurs, writers, artists, musicians, and others to purse their businesses without worrying about starvation. The question would be which group would be the most common. I suspect the latter. Such a plan would require financial education to be part of everyone’s curriculum and a willingness among the wealthy to endure short-term income decreases (they stand to benefit in the long-run as investors).

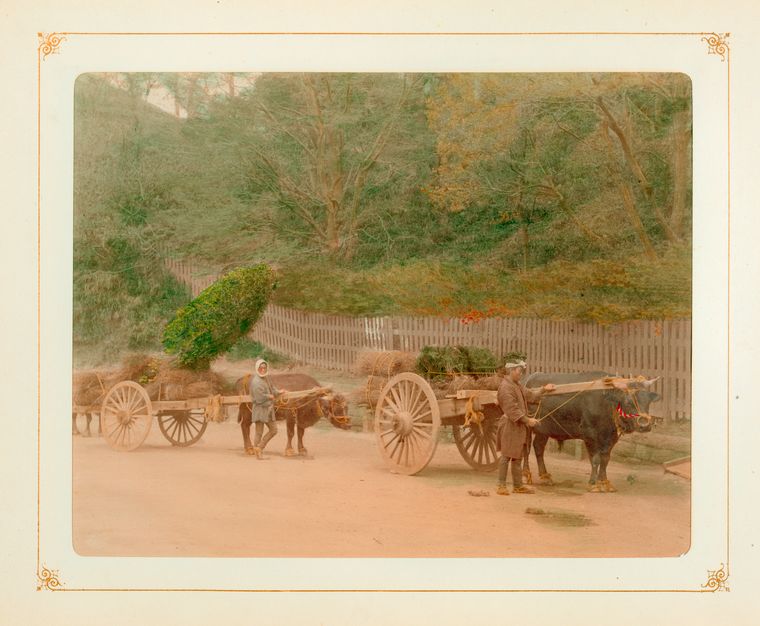

Of course, my opinion is shaped by my Christian perspective more than my study of Japan, although the Edo period redistribution and investing system is interesting. During the Edo period, merchants tried to eliminate all their liquid assets through community projects and spending. This helped them avoid the samurai confiscating their wealth and helped usher a sustainable economic boom. In any case, in my Christian tradition Jesus was blunt. He believed the rich should concern themselves with the poor instead of their riches (Mark 10). Likewise:

All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need… No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had… there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need. (Acts 2:44-45; 4:32, 34-35)

These verses don’t support socialism as we modern think of it, however. In these examples, the wealthy would give some of their assets to help the poor. It doesn’t say these people sold all of their assets. Rather, they sustainably supported the poor in the community. I like to call this responsible capitalism.

This article is a little different from what I usually write. I don’t delve into economics on JP, but I often about the subject. Some online articles speak of how the US could learn from Japan’s limited income inequality. However, Japan has different circumstances than the US as I sketched. The country also has a different set of cultural values which impacts its economic system. The US could gain a few ideas from Japan, but we have to keep these differences in mind.

References

Henderson, D. R. (2020). The Truth About Income Inequality. Reason, 51(9), 32–37.

Huang, Eustance (2020) Japan’s middle class is ‘disappearing’ as poverty rises, warns economist. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/03/japans-middle-class-is-disappearing-as-poverty-rises-warns-economist.html

Koll, Jesper (2020) Japanese capitalism can teach U.S. lessons in income growth and equality. Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/11/13/commentary/japan-commentary/japanese-style-capitalism-us-income-growth-and-equality/

Rugaber, C. S. (2013). Economists Say Inequality Hurts Us All. Skanner (Seattle, WA & Portland, OR Combined Edition), 35(12), 1–3.

I’ve been noticing a trend among Americans that like to look towards Japan for answers, as if it has things figured out.

I don’t know about that. It may look attractive on the surface, but whatever “success” it may have in the eyes of Americans come with hefty social shortcomings that mere numerical data doesn’t show. Japan may look “modern” and “civil”, but what it really is is a stifled, stunted society trying desperately to keep up this image.

Having been a student and a worker in Japan opened my eyes. Japanese society is a very “unthinking” one that still depends and operates on the senpai-kohai mentality to get things done. In my view, this is the main issue as to why Japan cannot and hasn’t recovered its position in the post-bubble era. You can see it start right at the heart of the educational system, which is remarkably poor. Children are raised and brought up to be good memorizers and system followers, not to become self-realized adults adept at making decisions. What you’ll find is a society that tries to make things predictable for everyone to carry on life without much thinking. Not necessarily because they care so much about human welfare, but because the culture dictates that you keep systems intact and predictable, don’t overstep on others or rock the boat. This has far-reaching consequences.

It has to be said that you can’t simply transplant what Japan has to the US. What they value and expect in life and how money is viewed, generally, is totally different. The “pursuit of happiness” isn’t a concept here. Besides, anything you’re used to in the US, Japan has MUCH less of it: time, money, space, choices in general. Everything in Japanese life is linear and tighter, which is why many Japanese people have little to no hobbies as adults and require weeks ahead of time to plan even a simple dinner date with friends. I was much more productive in the states; what I could do in a single day there requires 3 or more days in Japan for the same amount of things. Certain freedoms beget certain freedoms.

My landlord and friends are investors, but they invest only in American stocks. They don’t invest in Japanese stocks, heck no. Also, from Christmas to Easter season, Japanese banks and brokerages advertise an American flag on their buildings. Why? It’s the season where they encourage Japanese savers to convert their savings into US Dollars. Not Euros, not British Pounds. US Dollars. It’s because from December to March, Japanese people aren’t spending while Americans are, so during this particular time of year, the JPY-USD rate is low for the Japanese. They convert savings to USD in that period to hedge their money.

I attended university in Japan for business and economics. I was also a business major in America. What they teach in Japan is straight out of what’s taught in America, with many Japanese professors having studied and worked in America and took the knowledge back. It’s a high status in Japan if someone is able to live abroad, have international education, global experience, and have English ability. In order to be a top manager in a Japanese company, English test score is taken as the biggest factor. One of my neighbors worked in the US for 9 years and he admitted straight out that a lot of what’s done in Japan is, in his words, “the wrong way”.

I guess this is a long way of saying that it’s hard to truly know and understand a country’s situation if you’re not an active participant in its society. I find a lot of Americans prop up Japan misguidedly and erroneously, a serious case of how the grass is greener.

Thank you for your details thoughts, Mark. I’ve also seen many think Japan has all the answers. I prefer to look at different cultures and time periods for possible lessons we can apply today, which is what this post seeks to do. As you say, however, there’s a danger in lifting these lessons from the culture. They don’t always take root in different cultures, but sometimes they do in ways you can’t predict.

In terms of average IQ, Japan is the smartest nation on the planet (even though he IQ tests are biased in favor of Europeans) .. That is why people think they have things figured out. I think Japan’s unique culture is a function of self-imposed isolation for hundreds of years. Must say, I didn’t like Abe – too conservative in mindset. And his economic plans were bad too, from what i can tell. (For full disclosure, I am a retired scientist (at 31), non-religious democratic socialist BuJew. (aka Buddhist [as a philosophy] and Jew [by ancestry]). By extension- I lean pacifist. – so, as a cliche; Einstein, except for the genius part.

What is unmentioned in the article is that Japan has one of the highest debt to GDP ratios- twice that of the USA. In my view, neither country will exist in a few years. In the USA, this is because of our addiction to military overspending and liberal as well as corporate tax subsidies. All other country’s military budgets are a reaction to ours. But we havn’t been reducing it, and have made WWIII much more likely, by provoking China and Russia. We fail to realize that they lost ~45 million to the anti-Communists during WWII, barely managing to kill about 5.5 million Nazi soldiers (which was 84% of their entire force).

Those Bible verses seem to have a heavy communist influence, but really Marx was raised as a somewhat devout Christian. He “stole” many Communist and socialist ideas from the descriptions of the early church in the Bible. His core teaching differs from that of Jesus, though. Jesus says if you are a slave – try to be a *GOOD* slave. (Which is one reason why Marx called religion an opiate.) The goal of Marx and of socialism, according to Einstein’s “Why socialism” essay “is is precisely to overcome and advance beyond the predatory phase of human development.”

I’ve pondered Japan’s economic fate because of that debt and the decline of its population. There will be a time when the working population of Japan won’t be large enough to meet those debt obligations. I’ve also wondered if a world-wide Jubilee isn’t in order soon. Of course economists scoff at the idea, but money doesn’t exist. It’s all a mental construct; as a construct, we can make it do whatever we want it to do. However, this would require a collective agreement among all the world’s governments and debt holders.

How much does the US economy depend on that military spending? There’s a cascading effect to it, so cutting off the top may well cause a plunge in economic production, which would be politically untenable.

This posts reminds me of the idea of democratic capitalism, which was a thing in the U.S. for a while. https://aeon.co/essays/postwar-prosperity-depended-on-a-truce-between-capitalism-and-democracy

I would love for that idea to come back.

Thanks for the interesting article!