Japanese folktales have layers that require some thought to fully understand. Of course, Grimm’s fairy tales and even the Bible require reflection too. Context matters for understanding any sort of literature, but context becomes critical when dealing with stories from cultures other than your own. Culture provides a background and a common language of symbols that encapsulate deep ideas. If you don’t comprehend these symbols, you can’t understand all the nuisances of a story. You can understand the main meaning and still enjoy the story, but you can also misunderstand some aspects. Let me turn to an example from the Bible:

You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if anyone would sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well. And if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles.

Matthew 5:38-41.

Most people interpret this section as doing more for people than they ask, including your enemies. It’s seen as the principle of nonviolence. This is only a partial understanding, however. If you look at the context of Roman culture at the time, more messages appear. In Roman culture, a superior would backhand an inferior with their right hand. By turning the cheek, you force the superior to slap you as they would an equal: using the palm. Likewise, the cloak was an item of clothing that couldn’t be taken from another legally. By giving up the cloak, you would stand in front of your enemy nude. In the culture of the time, witnessing someone else’s nudity in public was a social shame on you. It showed how you had wronged that person. Finally, Roman soldiers were allowed to force someone to carry their gear for a single Roman mile. However, if they forced the peasant to go further, the soldier could be whipped and lose a month’s pay.

Jesus was advocating passive resistance, or “killing them with kindness.” It was quite a socially provocative stance. But to get the message, we have to understand the rules that governed the culture at the time.

So when it comes to Japanese folktales, you need to consider the type of story. The types differ based on socioeconomic class. Old stories have four types: myth, hero, urban, and folk. The types overlap with each other. However, generally:

- Myths deal with religious or cultural identity stories.

- Hero stories focus on the warrior and samurai class.

- Urban stories focus on the experiences of the merchant class.

- Folk stories deal with the viewpoints of the farming class.

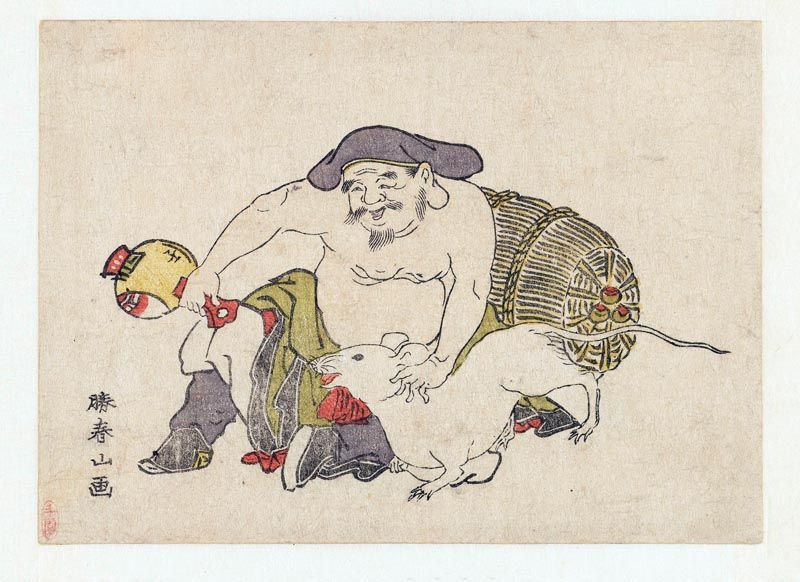

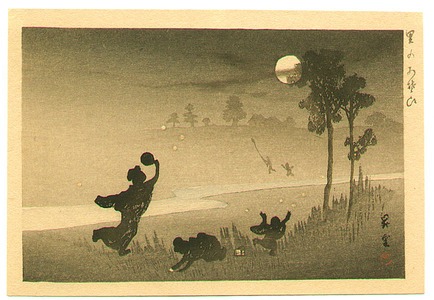

Folk stories and urban stories often poke fun at the samurai class and at mythology. Many of the stories showcase farmers and merchants getting back at the ruling class for their comeuppance. As you can guess, folk stories feature the natural world. You find stories about foxes and other animals here. Merchant stories often have spirits, demons, and moral tales of greed. Samurai stories tend to focus on battles and reaffirming their special status. Samurai vanquish ghosts and demons through their wits and swordsmanship.

Sometimes you find urban and folk stories where a person becomes a part of the samurai class through their hard work. Think of this as modern-day rags-to-riches stories; they rarely happen. But the stories inspire people. Let’s look at a story with these contexts in mind.

Raiko was a wealthy man living in a certain village. In spite of his enormous wealth, which he carried in his obi (sash), he was extremely mean. As he grew older his meanness increased till at last he contemplated dismissing his faithful servants who had served him so well.

One day Raiko became very ill, so ill that he almost wasted away, on account of a terrible fever. On the tenth night of his illness a poorly dressed bozu (priest) appeared by his pillow, inquired how he fared, and added that he had expected the oni to carry him off long ago.

These home truths, none too delicately expressed, made Raiko very angry, and he indignantly demanded that the priest should take his departure. But the bozu, instead of departing, told him that there was only one remedy for his illness. The remedy was that Raiko should loosen his obi and distribute his money to the poor.

Raiko became still more angry at what he considered the gross impertinence of the priest. He snatched a dagger from his robe and tried to kill the kindly bozu. The priest, without the least fear, informed Raiko that he had heard of his mean intention to dismiss his worthy servants and had nightly come to the old man to drain his life-blood. “Now,” said the priest, “my object is attained!” and with these words he blew out the light.

The now thoroughly frightened Raiko felt a ghostly creature advance towards him. The old man struck out blindly with his dagger, and made such a commotion that his loyal servants ran into the room with lanterns, and the light revealed the horrible claw of a monster lying by the side of the old man’s mat.

Carefully following the little spots of blood, Raiko’s servants came to a miniature mountain at the extreme end of the garden, and in the mountain was a large hole, from whence protruded the upper part of an enormous spider. This creature begged the servants to try to persuade their master not to attack the Gods, and in future to refrain from meanness.

When Raiko heard these words from his servants he repented, and gave large sums of money to the poor. Inari had assumed the shape of a spider and priest in order to teach the once mean old man a lesson.

This urban story teaches against greed. But the story also warns people about reaching beyond their social station. Raiko disregards and even tries to kill the priest. Priests acted as a kind of aristocracy in their own right; at times even samurai listened to them. Ignoring them violated the order of society. During the Edo period, the merchant class sank their wealth into public works projects and other projects. They did this to avoid the samurai class confiscating their money, but this soon became a part of the merchant’s role in society.

So in context, the story teaches against greed and against reaching above one’s station: meanness, in a word.

One more example! Read the Story of the Two Frogs. In the tale, two frogs mistake their own towns for their destinations. The tale speaks about people who fail to appreciate the differences between towns. It also speaks to a rivalry between Osaka and Kyoto as economic and cultural centers. Yet the story also jabs at farmers who don’t know the differences as a merchant would; certain products and services will sell better in one city and not in the other. Finally, the story warns people not to mistake the economic power of the merchant class (Osaka) against the older cultural power of the samurai and imperial class (Kyoto).

Of course, there’s a danger of reading too much into stories. During my literature classes, I felt troubled by how much is read into Shakespeare’s plays. Sometimes a story is exactly as it appears and lacks any hidden meaning. But it’s best to read stories with an eye toward their context. We can’t assume to know how people would read the story in its period. Our modern age stands too far away from the context.

So we have to remain humble when we read and not project our modern sensibilities on the stories. Christianity often falls into modern projection, for example. The Book of Revelation is usually read from a modern perspective rather than the perspective of a 1st or 2nd century Christian living in the Roman Empire. It’s difficult not to bring our views to what we read so I ask myself these questions:

- What makes me uncomfortable? Why?

- What do I find agreeable? Why?

- Am I reading too much into this story?

- What do I know about the story’s time period?

- Remember that my knowledge of the culture and time period remains limited.

I try to approach stories with humility instead of bringing my knowledge with me. If something makes me uncomfortable or grabs my interest, I research it to understand it better. Anything that triggers my bias can be a sign of my modern perspective. For example, prostitution wasn’t seen as negative in Edo Japan. At least, not as negative as my modern Christian perspective sees it. Keeping this careful mindset can be difficult!

Whenever you read a folktale, keep the context of the tale in mind. Stories teach us much if we remain open to them. In fact, they are the oldest means of teaching and remain the best means. Whenever you read Japanese folktales, remember to enjoy them; they are not merely homework! People designed tales to entertain and teach. The word myth is used as a synonym for lie, but this misuse prevents us from seeing the truth myth tries to convey. Folklore and myth contain truths about human behavior that remains useful today.