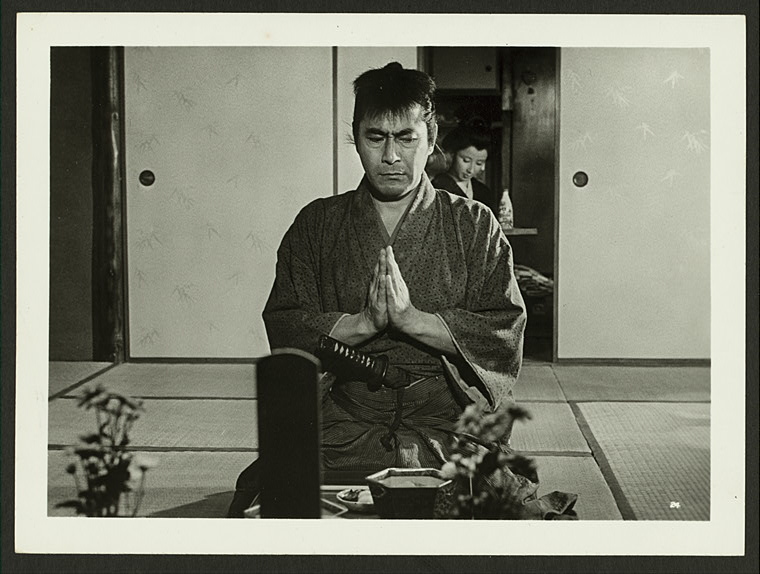

Bushido is the code of conduct for the samurai. It isn’t a written code. Rather, it was taught through example and through stories. As with any ideal, few people lived according to the tenants of bushido, but many aimed at it. Bushido comes down to 5 ways of acting. The teachings of Confucius and Mencius provide the backbone of bushido. Mencius expands on Confucius’s ideas.

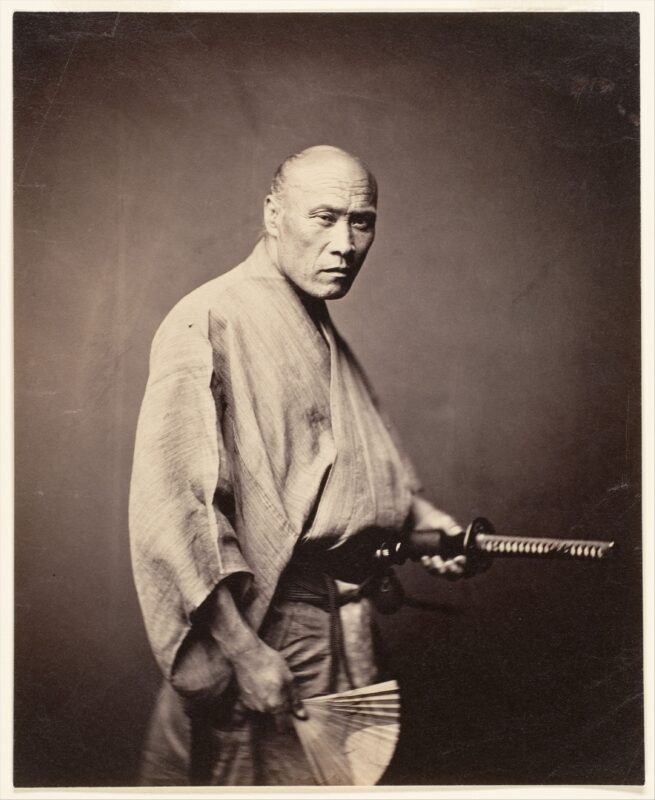

Although they were warriors, samurai were also expected to read widely and know their Chinese classics. But they were also warned not to be too well read. Samurai looked down on scholars, yet they could often out-debate those scholars. Samurai were expected to apply their knowledge and not merely know and read. Ethical emotion ruled the samurai intellect. Ethical emotion didn’t act on emotions like anger or love. Rather, ethical emotion comes from cultivating the 5 ways of acting found in bushido. Ethical emotion is a muscle that needed trained. Samurai practiced their swordsmanship so their muscles would react without needing prompted. Ethical emotion is spiritual swordsmanship. It reacts without a conscious thought after it is trained.

Act with Rectitude

Rectitude is “the power of deciding upon a certain course of conduct in accordance with reason, without wavering; to die when it is right to die, to strike when to strike is right” (Nitobe, 1900). Rectitude requires you to be honest and courageous. As Confucius writes, courage is doing what is right. It’s hard to decide on a course of conduct and always remain on it. It requires you to be honest about that course. but it can also make you a hard person if you take it too far. You could become unbending in your morality. Many samurai took this hard-justice path.

Of course, if you don’t have well developed reason, it becomes hard to act with rectitude. But that is where the other acts of bushido step in.

Act with Benevolence

Samurai were expected to act with affection for others and with sympathy for them. They were supposed to be benevolent to the weak, the downtrodden, and the vanquished. Of course, we know most failed to do this. Benevolence works against and with rectitude. It keeps rectitude from becoming too hard. Benevolence helps prevent stark black-white thinking. Benevolence acts as the reason that directs rectitude. But as Masamune writes, too much of it leads to weakness. It opens the samurai to exploitation.

Benevolence requires us to learn how to take on the view of others and to develop sympathy. Sympathy can be tough to cultivate. As Jesus teaches, we need to love our neighbors as ourselves; many find it hard to love themselves. Yet we learn to love ourselves by loving our neighbors. I admit, loving someone who is yelling at you, being annoying, and the like is difficult. Most of us would rather teach that person a lesson, usually with a fist to the nose. But learning to love these people teaches us how to love ourselves. You may despise yourself far more than you despise that rude heckler. So it should be easier to start with that heckler and keep practicing on those difficult people until you work up to loving yourself. Acting with benevolence takes practice, just like learning any sword stroke.

Act with Politeness

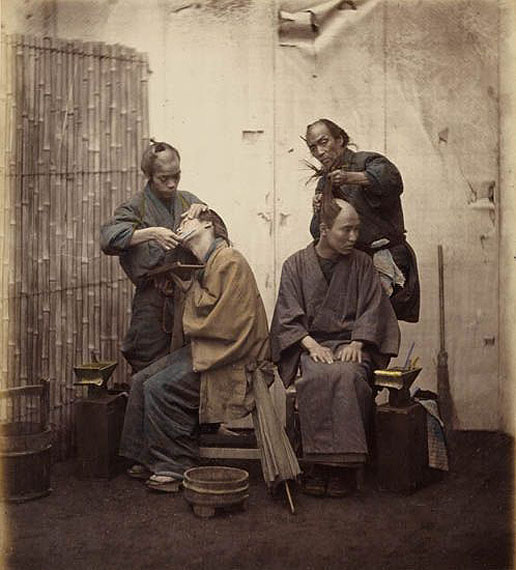

Politeness ties with benevolence because it respects the sensibilities of others. Politeness involves small acts of kindness, such as allowing someone to get in a line ahead of you. It means not cursing or speaking loudly. Politeness acts as daily exercise for Benevolence and Rectitude. It’s the application of your knowledge. It also sets you apart from the people who act and speak crude. Politeness is an act of love for your neighbor. Samurai would use the tea ceremony to practice politeness.

Act with Loyalty

Loyalty proves rather difficult for Westerners, at least, as samurai understood it. Samurai were expected to be loyal to their lord, even to the point of suicide. Loyalty was homage to a superior. That homage meant you tried to anticipate what the lord wanted. Today, we can be loyal to a spouse or to God or to work. That means we try to anticipate actions they need done.

Act with Self Control

Self control demands we remain calm in all situations and reason through it. Self control exercises the muscles of ethical emotion and itself in the process. Self control seems to move our emotions in the right ways through conscious effort. And this is hard! Self control comes down to practice. If we think and speak negatively about people, we can’t cultivate benevolence. It exercises the wrong muscles. Rather, you have to challenge those thoughts whenever they arise. Each time they arise. And the act of challenging those thoughts every time is self control. Although they can be difficult to manage, emotions belong to you and are under your control (unless you have some sort of brain disorder). Emotions and thoughts gain momentum that takes time to change. When you are learning how to use a sword, you have to first unlearn your habitual wrong movements and replace them with the proper movements.

Whenever you learn anything new, most of the time is spent unlearning our preconceived ideas. Self control involves self reflection, knowing your pattern of reaction and thinking. Then you dismantle those patterns and replace them with new patterns. For purposes of this article, you will replace them with benevolent thoughts toward yourself and others, rectitude, politeness, and actions loyal to God or whatever you place as a superior. It can take you years of daily and hourly work to retrain your ethical emotion. Let me give you a personal example:

I worked retail for 15 years before getting into libraries. Retail made me hate people. And I mean that. I loathed them. As an introvert, I resent forced socialization. That’s all retail is. I would think dark thoughts about people, unChristian thoughts. This went on for years, and those muscles grew strong. I also didn’t like myself. Well, I eventually got tired of feeling unhappy with myself so I began to work my sympathy muscles and love-for-other muscles. I would tell myself stories about why people acted like dunces. I would try hard to think of one positive thing about each person I was forced to meet.

It was hard. Granite hard.

But over years those muscles grew stronger. My ethical emotion grew stronger. One day, I discovered I didn’t detest people anymore. Well, most of the time. My thoughts naturally viewed people as positive, including those who were yelling at me over a candy bar. My stories automatically kicked in, allowing me to feel sympathetic toward them. I also discovered I had become comfortable with myself through my practice of becoming comfortable with others. But whenever I wavered in my practice, those old feelings of resentment would resurface. Just as swordsmanship skills fade without practice, so too these skills fade if not practiced daily. Once you commit to the path, it is for forever.

About Honor

We can’t discuss samurai without discussing honor. Honor is how others see you and how you see yourself. You don’t have to pursue honor. You gain honor by following the 5 acts of being a samurai. Honor can be taken to extreme, but it shouldn’t be a focus of any samurai. Dishonor comes from breaking any of the 5 acts. It means you give into base emotion or fail to constantly exercise your ethical emotion. Many samurai killed themselves when they dishonored themselves because they had already killed their spiritual self. The mistaken idea of honor has cost many men and women their lives.

Bushido has many problems with it. It has led many people to suicide, particularly the idea of loyalty. I don’t want to gloss this over. But as an ideal and an approach to life, it can be useful.

Living like a samurai is a lifelong pursuit. The 5 acts set an approach to life that compliments your existing spiritual beliefs. It’s also a hard walk. As Aristotle wrote, happiness is the goal of life. But happiness also takes daily effort. Ethical emotion, just like a muscle, gets weak if it isn’t used everyday. This daily effort generates honor along with long-term happiness. Although like any exercise, you won’t necessarily feel happy if your ethical emotion is weak. But keep at it, and it will strengthen. You too can live the life of a samurai on your own terms.

Reference

Nitobe, Inazo (1900) Code of the Samurai, Bushido: The Soul of Japan.

it’s very interesting to learn about samurai culture and how skills are coupled with a high degree of moral standards. I would imagine how this class of people live such an honorable life strictly in accordance with their values. I now understand why swordsmanship sports today have such strict discipline in their training.

The samurai writings we have are ideals that varied with each region. Bushido didn’t become a system of thought until around the 1900s, leading up to the kamikaze and other suicidal thinking. Before then, it was more an attitude than a code. Interestingly, many of the early writers wrote against suicide, which the later nationalistic bushido ignored. Death, however, remained at the center of their thinking because it taught appreciation for life.