Paper fans symbolize Japan, right up there with giant robots, sushi, geisha, and kimono. While a humble part of fashion and summer, the fan has a history of its own. Japan isn’t unique in having fans. It’s the most convenient way to cool off, after all. A leaf or anything flexible can become a fan, but fans also served as part of ceremonies and as symbols of power. Egyptian Pharaohs owned large ceremonial fans as various stone carvings and wall paintings attest, but the oldest known surviving fans, two woven bamboo hand screens, were found in a Chinese tomb dating to around 2 BC (Yelavich, 2009). That’s the issue with fans–they didn’t survive.

Victorian ladies developed a language for fans–just as they developed a language for flowers. Despite fans appearing throughout Japan, Japan didn’t develop a fan language. In fact, the Victorian love for fans came from contact with Japan and its exoticism. The Victorian fan language involved gestures such as touching the right cheek to mean “yes” and the left cheek for “no.” A fan snapped closed may signal jealousy, and a fan dropped to the floor is a pledge of fidelity (Yelavich, 2009). Fans retired in the West after World War I outside of dancing and a few other areas. Ironically, the Japanese disdained the fans they exported to the Victorian West (Hart, 1893):

There is a grate [sic] difference between the excessively cheap, vulgar and trashy Japanese fans that are made to meet the foreign demand for such goods, and the exquisitely artistic fans used by the better class of Japanese society. The Japanese themselves have a most profound contempt for the cheap, gaudy, stenciled products, which are exported by the hundred thousand to meet the European demand, and no self respecting Japanese will either look upon or would use such products.

Japanese fans appeared throughout everyday life, especially for the aristocracy. People used them as memo pads, road maps, fashion, and as a part of etiquette. When offering a gift in the Edo period, you presented it on a half-open fan. When bowing on the floor, you laid your fan ahead of you. This little gesture actually saved a man’s life.

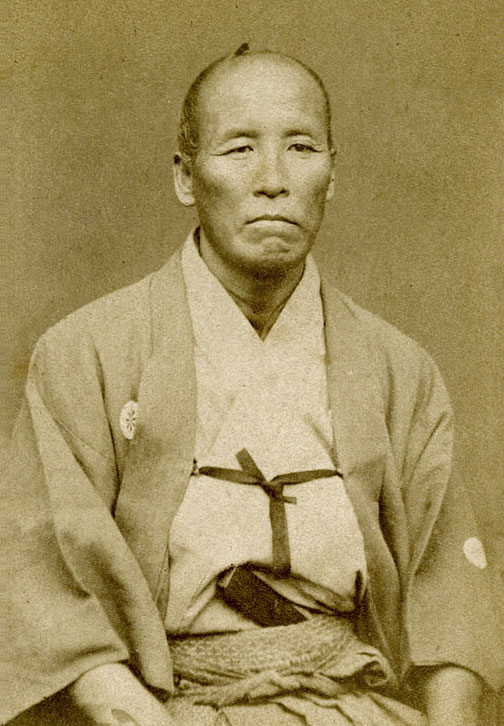

Araki Murashige was a samurai caught in a conspiracy during the 1500s. The Lord Oda Nobunaga summoned him, but Araki wasn’t a fool. He knew his life was in danger, but he couldn’t ignore the summons. Well, at the time a vassal had to bow to his lord before entering a room in a way that brought his neck right above the groove that kept sliding doors in place. You can imagine how many used this to as a way to off someone they didn’t like. This happened to Araki. As he bowed, the double doors came flying at his throat, only to smash against his iron fan which he had placed inside the groove. Araki acted as if nothing had happened and Nobunga reported reconciled with him and granted favors (Casal, 1960).

The iron fan Araki carried, called a tessen, is a relative to the war fan, or gunsen, that generals used to signal troops on the battlefield. Both were made of steel, wood, and paper and lacquered to help them resist the weather and enemy weapons. They became a part of a sword dance style that appeared during the Meiji period as we shall see. The war fan descended from the Chinese practice of generals carrying a horse-tail whisk as a symbol of their power. In Japan, military leaders first used a tassel of leather or paper strips called a saihai to do the same, but steel war fans eventually replaced these symbols of power.

The Japanese History of the Fan

The oldest Japanese reference to a fan appears during the time of Emperor Yuryaku (457-479). The emperor ordered a purple, leaf-shaped fan attached to a pole that was meant to be an ornament for the palace (Casal, 1960). Hand-fans were imported into the Japanese court or were sent as gifts from the Chinese and Korea courts. However, a reference dating from 763 AD showed scholars also used fans. In the reference, the emperor grants permission to Jozo, a wise, old and sickly man to appear before him. The text also allows Jozo to carry his staff and uchiwa, a stiff, rounded fan. It shows how these expensive fans were exclusive to nobility.

Over time, folding fans replaced the stiff wooden fans of China. They came in two classes: ogi, a folding wooden fan, and the sensu, a folding paper fan. We are more familiar with the sensu than the ogi. Japan inveted the paper folding fan (Casal, 1960), but no one knows for certain who invented it. Of course, we do have a few stories.

One record states a hermit named Toyomaru made an expanding fan which he presented to the Emperor Tenchi (662-671). But a more reliable record by the scholar Minamoto no Shitagau states many different fans existed at the court of Emperor Daigo (898-930), including the folding fan. Fujiwara Tadahira (880-949) had a reputation for carrying a fan painted with a cuckoo, and he would always open his fan and imitate the cry of the bird. Over time, Chinese fans faded from the courts in favor of the Japanese invention. These fans were still large, however. Too large to tuck into a sleeve. Rather people tucked them into the sash or the breast of a kimono.

In another fun story about the paper fan’s invention, Emperor Gosanjo (1069-1073 AD) had a favorite fan with slats cracked in several places. He was a thrifty emperor and high-quality fans at the time could cost 15 bushels of rice. So he pasted paper at the back of the fan to keep it together, accidentally improving the functionality of the wooden fan and eventually leading to a fan that could be tucked into a kimono sleeve.

No matter who invented the folding paper fan, it become a part of Japanese culture. Different types of fans become associated with men and women and their social standing. For example, the hi-ogi was a fan for married court women. These wooden fans were painted like their paper cousins and ranged from 8 wooden slats to 40 narrow slats. Married court women would only carry the 25-28 slat varieties (Casal, 1960). Men carried the heavier 8-10 slatted iron or steel tessen. Paper fans during the Tokugawa period used as many as 3-5 sheets of paper to create their fans instead of 2 sheets for the front and back.

Sadly, despite their importance and commonality, wood-block printed fans and other paper fans are scarce. However, the stories that involve fans survive, such as this one about Yoshitsune (Casal 1960):

Once there was a battle between two armies, the Genji on the one hand and the Heike on the other, at Yashimae. The Genji force was drawn up on the shore, while the Heike men in boats on the sea were lined up opposite them. Suddenly a single small boat was dispatched from the Heike fleet. At her bow a long pole was set up, surmounted with an open red fan. In the boat a court lady beckoned to the Genji army, as though challenging them to shoot at the fan with an arrow. The boat was bobbing up and down on the waves, and the fan wheeling round and round in the wind. It was extremely difficult even for the most skillful archer to hit it at once. The commander of the Genji army, Yoshitsune, called out to his men: “Is there anyone who will shoot the fan off?” One of his retainers came forward and said: “There is a very skillful archer among us called Nasu no Yoichi, who can without fail kill two birds out of three flying in the air.” The commander, pleased with the answer, summoned Nasu no Yoichi to appear before him, and ordered him to try his skill.

Yoichi wished to be excused, but Yoshitsune insisted on his venturing it.

Resolved in his heart that in case he should miss the mark he would not live, he rode out into the sea, and looking forward with his bow ready, saw that the boat was rocking so much that he could not fix his aim. He shut his eyes in prayer for some time, and when he opened them he felt that his nerves were more composed, and the boat more tranquil. Setting a shaft to his bow, and taking his aim carefully at the object, he let it fly. The arrow hit the fan at the pivot, breaking it into two or three pieces, which flying up into the air, drifted slowly down upon the waves.

The Genji army, Yoshitsune himself among the rest, leaped for joy till the shore rang with rapture, and even their enemy, the Heike, spontaneously applauded by striking their weapons against the sides of their boats.

Fan and Sword Dancing

As we’ve seen, fans have a long military history as a signal for war, as a defensive weapon, and as a part of military legend. The fan soon became a part of sword dances.

Sword dances date back to the Heian period (794-1185), but developed during the Tokugawa period (1603-1868) and became the form we know of during the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji period saw the samurai class outlawed. The new laws forbade swords and traditional samurai hair styles and dress in public. Families who wanted to keep the samurai arts were forced to turn toward entertainment. Sakakibara Kenkichi formed a company in 1872 that did just that. The company toured and produced martial-arts inspired productions where ex-samurai would flash their swords and perform feats of skill. Martial art dances, kenbu, featured in these productions too (Fan and Sword, 2006).

After World War II, the Occupation Forces forbade the use of weapons in martial arts practice and entertainment, so kenbu performers substituted fans for their swords, changing the choreography as needed. The new style, called shibu, continued even after the the government lifted the weapons ban in the early 1950s. And many performers did both styles, sometimes separate and sometimes combined.

A few rules of the performance apply.

- Performers never touch the sword beyond the spine of the blade. This not only avoids slicing off fingers, but also it avoids damaging the blade with sweat corrosion.

- The sword always remains in the hand. There isn’t any sword tossing in the technique.

The fans used in these performances were modeled after the gunsen and tessen but were made of paper and wood instead of lacquer and steel. The latter would be too heavy to use in the dance.

The humble paper fan has a rich lore and history for being what is a throw-away item. It is possible that fan-culture will make a comeback as summers grow warmer and longer. Fans would lend a personal touch, particularly if the fans are hand-made, to everyday life.

References

Casal, U.A. (1960). The Lore of the Japanese Fan. Monumenta Nipponica. 16 (1/2) 53-117.

The Fan and the Sword: Exploring Kenbu. (2006). Journal of Theatrical Combatives, 1.

Hart, E. (1893). Japanese Fans. The Decorator and Furnisher. 23 (1). 26.

Yelavich, S. (2009). A breezy history of hand-held fans. ID 56 (2). 88.

Very interesting. I’ve got a few fans from Japan but I didn’t know all of the history behind them. Cool.

It’s amazing how many everyday items have a deep history.