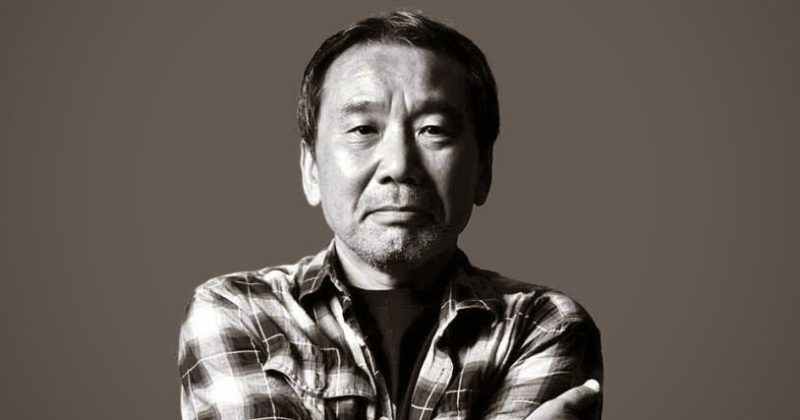

Haruki Murakami writes bestselling postmodern surrealist fiction. His work often focuses on loneliness and alienation. I’m writing this article in response to a reader’s question about how he writes about women. I’ll focus on two books Kafka on the Shore and 1Q84. This article will focus on sexuality and will quote explicit passages from Murakami’s works.

Haruki Murakami writes bestselling postmodern surrealist fiction. His work often focuses on loneliness and alienation. I’m writing this article in response to a reader’s question about how he writes about women. I’ll focus on two books Kafka on the Shore and 1Q84. This article will focus on sexuality and will quote explicit passages from Murakami’s works.

As a postmodern writer, Murakami likes to toy with literary conventions, often self-referencing how you are reading a story and how the characters are story characters but don’t know it. He also likes to pull in rather needless elements. In 1Q84, he quotes from the Tale of the Heike and other Japanese literary texts. However, the quotes have little to do with the story. Rather, they point out the character’s level of intelligence and Murakami’s familiarity with literature. You’ll see prostitutes quote Hegel in Kafka, and other philosophic interplay. None of these references had any importance to the stories. In fact, I started to skip over them and still understood what was going on and the “philosophy” Murakami attempted to show. And I am the type of person who reads Nietzsche and Aristotle for fun.

1Q84, in particular, could’ve used pruning. I would suggest 300-400 pages could’ve been cut without impacting the story and themes. The book references George Orwell’s 1984 (which I’ve read several times) but felt disjointed. 1Q84 involves a mysterious world that seems to mirror our own. It follows a pair of long-lost lovers, Aomame and Tengo, as they become involved with a religious cult and mysterious entities called Little People. Aomame works as an assassin. Tengo is a writer who agrees to ghost write a novel written by the seventeen-year-old Eriko Fukada.

As I read the novel, I struggled to imagine the characters as real. Instead, they felt like anime characters. Eriko, in particular, felt like Rei from Evangelion. They shared the same behavior and sexual significance.

Kafka on the Shore follows a runaway 15-year-old boy and explores his psyche. The story retells Oedipus in a postmodernist way with dream sequences. It delves into teen male psychology. Kafka, as the 15-year-old renames himself, spends his time reading in a library, delving into books by Natsume Soseki and others. He soon falls for the librarian Miss Saeki, which becomes the main source of the story’s themes.

Murakami often pans over the bodies of women with pornographic detail:

Tamiki’s skin was soft and fine. Her nipples swelled in a beautiful oval shape reminiscent of olives. Her public hair was fine and sparse, like a delicate willow tree. Aomane’s was hard and bristly. They laughed at the difference. They experimented with touching each other in different places and discussed which areas were the most sensitive. Some areas were the same, others were not. Each held out a finger and touched the other’s clitoris. Both girls had experienced masturbation–a lot. but now they saw how different it was to be touched by someone else. The breeze swept across the meadows of Bohemia.

At the same time, he fixates on the penises of male characters and giving their bodies a cursory description. Both Kafka and 1Q84 spend a lot of time focused on sex. So much that it hurts the flow of the story. Few of the sexual encounters matter for the story, yet the encounters seem to point at Murakami’s perspective of women. Murakami often portrays women as vessels of liberation for the male characters. Sex with them validates male existence.

In both of the books, he views the flaccid male as useless. He often refers to this “lying in the mud.” This phrase has several layers to it. On the surface it refers to how the male is dirty, like mud, and mixed up. Mud is made when “pure” water mixes with soil, when male purity mixes with lust. The phrase also references Buddhist symbolism of the lotus rising out of the mud. It suggests men receive salvation through their erections and joining with women:

Tengo’s penis began to wake from its tranquil sleep in the mud, as if it had been poked in its back by a finger. It gave a yawn and slowly raised its head, gradually growing harder until, like a yacht whose sails were filled by a strong northwest tailwind, it achieved a full, unreserved erection. As a result, his hardened penis could not help but press against Fuka-Eri’s hip. Tengo released a deep mental sigh. He had not had sex for more than a month following the disappearance of his girlfriend. Probably that was the cause. He should have continued multiplying three-digit figures.

“Don’t let it bother you,” Fuka-Eri said. “Getting hard is only natural.”

Tengo feels guilty about it, yet the 17-year-old Fuka offers him acceptance in the scene. Acceptance for the male appendage by women appears often in these two books. Kafka has a scene where the transgender character Oshima (Oshima has a female body and a male brain, yet is often shown as female by Murakami despite referencing Oshima as “he.”) compliments his. Murakami speaks to a common male concern that Viagra commercials prey upon. Acceptance of the penis translates to a woman accepting the entire guy as a person.

At the same time, Murakami portrays women as distant and unreachable. Aomane, despite being a point-of-view character, retains this vibe throughout 1Q84. In fact, this becomes a plot point as Tengo never gets close to her. She has to get close to him.

Murakami falls into the goddess problem with these two works. The male characters need women to become whole. For Kafka, he needs Miss Saeki to come to terms with who he is. For Tengo, he needs Aomame to become whole and escape the parallel world he’s caught within. Aomame also needs Tengo for the same purpose, but she still remains out of reach for him unless she decides, like a goddess, to find him.

The goddess problem puts women into a shrine for men to worship. It is another form of chauvinism. Whereas chauvinism considers men superior to women, the goddess problems considers women superior to men. In both cases, women end up objectified and serving male needs. In chauvinism, she is expected be a servant. In the goddess problem, men serve her but with the desire for acceptance and liberation. In both cases, women are used instead of being treated as people. They become a means to an end.

Kafka on the Shore and 1Q84 strike me as reactions to the rise of militant feminism and the disparagement of men. The male characters look toward women for a reason to exist as whole people, to have a purpose. They almost appear to ask for forgiveness, just as Fuka-Eri offers Tengo for his erection. It places the male characters in a subservient position similar to what women endured before the women’s rights movements. Murakami’s men feel guilty for their sexual urges.

Both books felt like soapboxes for Murakami. He spends his prose indulging his interests, in women’s bodies, in literature, and in poking the eyes of literature. For example, he references Chekov’s gun in both books. Chekov’s gun is the idea that if a gun appears in a story, it needs to be fired. He thumbs his nose at the idea that everything in a story needs to have a purpose. His characters are overly sexual, making me think of a teenager’s writing. Now, Murakami has won awards and is one of the most important modern Japanese authors. So he knows what he is doing. But the stories rubbed against my sensibilities as a male, a writer, and as a Christian. Tengo and Kafka tied too much of their identity with their sexuality. But then, that is what people do now. Sexuality has become a marker of modern tribal identity as much as politics has become a marker.

Frankly, people let their baser instincts drive them too much. In the ancient world, virtue sought to restrain and channel them instead of letting those animal instincts guide us. Murakami’s characters fall into hedonism and fall far from virtue. They let their base instincts drive them, and they often struggle to see reality from fantasy. In both instances, Murakami is certainly a writer for our time.

I like murakami, probably because I’m a lonely and alienated young men who lives in a big capitalist city, I was aware of the problematic writing of woman, but still manages to land his appeal in his vage narratives where one can proyect their own lived experiences(and failures).

I seen his books be described as incel literature and I think is probably acurate to some degree, like you point out in this common false dichotomy of seeing only servants/goddess in woman, analogous to the incel black/beta and white/alpha mentally. While im not an incel myself, I would consider myself at least adjacent to the archetype. It never occurred to me but the anime comparison is also very interesting, much of his work could be undersood as anime genre’s and tropes.

But while I don’t watch anime much now a days as even to me feels very teen focused, murakami obviously as writen format has a lot more liberties to explore more usually censored stuff like sexually, so he can fill a world nat is more appealing than anime, but still going by a lot of their modus operandi, which the normalized common japanese way of protraying woman in media which is very misogynist, and extremely out of reality obvious in the boob proportion but what for the anime viewers becomes normal, as is the mysterious girl in a murakami book.

While I don’t think his writing is a response to the “sexual war” or feminist waves, he articules a fiction that enbodies the imaginary of still present young men. I would disagree that going back to old greek virtues would be a good idea, first in a marxist critique because the heroic ideal can’t match with a 9 to 5 job, but also the greeks are like the OG misogynist that landed us here in the first place, even Stoics(is the only virtue school I feel enough confident about commenting) would frequently fall into this woman are servant to men as serving men by being wife, mothers etc is their way of execicing virtue, and, the word virtue even goes directly with virility by definition a men only attributes this is completely incompatible with current understanding of equality, and sending young man with a virtue framework would end up in failure(like the distiction of reason and emotion, virtue seeking tells us to only listen to reason, this on the current world just makes you alienated to our own emotion, as you won’t have a woman as an emotional tissue paper when needed as in another historic moment) or end up cherrypickig and adapting it in a postmodern/selfhelp kind of way.

I need to read more Murakami, but first I’m slowly working through some older Japanese literature for more context.

You’re right about how many Greek and Roman writers were products of their time. That doesn’t mean we can’t take the ideas that remain valid and discard the ideas that no longer apply. Many ancient writers viewed women as superior or equal to men in their unique role as mother. Differing roles doesn’t necessarily mean inequity. Of course, I’ve read just as many ancient writers who viewed woman as little better than children or slaves. Women commanded many rights in the Roman period, such as the ability to own property and will that property to their children. The ancient world wasn’t as unequal as people nowadays suppose. During Japan’s Heian period, for example, noble women owned property while noble men were barred from owning property. They owned the income streams instead.

Marcus Aurelius didn’t write about alienating emotion. There were times he wrote about his sorrow over the deaths of his children. He wrote about how emotion shouldn’t rule actions. That’s the role of reason. If you read Seneca and Cicero, they suggest emotion should inform reason. The practice of virtue doesn’t remove emotion from the calculus. It warns we shouldn’t follow our emotions and whims as soon as we have them. Which is something I wholeheartedly think our age needs to do.

Quite interesting. Not being much of a fiction reader, my only direct exposure to Murakami is through, “…When I talk About Running.” After forty years of running, though never the kinds of distances Murakami has done, I nevertheless found his words on the topic to have well-defined some things I’d never really consolidated into clear ideas.

Running is both a physical and a mental endeavor. So is human sexuality. Both reflect some measure of maintaining the passions that challenge us to keep life engaging. And, “When I Talk About Running” is about Murakami’s *passions*, primarily for running and for writing.

Murakami acknowledged knowing he’d long ago peaked with the running. So it doesn’t much surprise me that Murakami puts such descriptive effort into sexuality and the grasping at passion that it represents. Though I can’t much comment on whether or not it’s important to his stories, or just so much… gun-waving.

I haven’t read his nonfiction. It might offer more insight into why his fiction focuses on what it does. He does have a way of using words. He doesn’t approach the filthy excellence of Nabokov, however.

Wish you could get your writing published in a media criticism-type journal.

This is excellent and thoughtful analysis as usual. Even though I’ve never read his work, the post feminism reaction take is a compelling one, since I have noticed that sort of genuflecting all throughout contemporary media… Especially while getting an art degree in Portland.

We sit in an interesting transition period. We can see this across literature, media, art, politics, government, and culture. I wish I could time travel a few centuries into the future and read books about our period of history!

Can someone please, please explain to me why Murakami is so popular? I’ve read many of his books and I still can’t fathom the reason. The only book of his that I actually liked somewhat was After Dark. At least in that book the main character is someone other than a middle-aged or teen-aged nobody male loafing around thinking about random things. However, Murakami’s other books are insanely boring at best. He’s actually gone on the record and said that he never plots anything in advance: He just writes whatever comes to mind.

I’ve pondered that about many New York Times Bestsellers. I’ve read Clive Cussler, and his books are all the same. James Patterson doesn’t even write his own books anymore, and of those he did, I found them dull and samey. Murakami is a literary writer, so his writing (what I’ve read of it and of the genre) doesn’t really differ that much in approach. It comes down to personal taste in the end.

No doubt it boils down to personal taste in the end. I’ve made an honest-to-goodness effort to appreciate his works, but I just can’t. Your post elegantly underscores many of the reasons why.

I always thought of Murakami as being rather sexist towards women what-with the weirdly vivid descriptions of their naked bodies. You could argue that he most certainly is. However, I never really thought about it from the angle of him actually worshipping them while simultaneously diminishing their male counterparts. It’s a very interesting perspective.

Cheers

Making such an effort is more than what most people do! Such effort still offers something to learn or even unlearn–as I have to remind myself.

Worshiping women appears in incel behavior too. That worship becomes a form of resentment, as strange as that sounds. Many extreme behaviors and modes of thinking end up circling back to their opposite. While writing the article, I wondered if that was the case with Murakami, if unconsciously, or if it was a veiled form of homophobia.

Thank you. This is a thoughtful critique and helps me to view both Kafka on the Shore and IQ84 with less idolatry and intimidation and more fair-mindedness: e.g., the Murakami-serving/reviewer-pandering, plot-distracting literary intellectualism, the oversexualization of people, and most compelling for me, the feminist-pressured tendency for male writers to portray themselves as inferior to women.

I’m glad you found the critique helpful.