Geisha are an icon of Japanese culture. Mystique and stigma surrounds the profession. Being a geisha is a profession, just as librarianship is a profession. Geisha are not prostitutes. Although, prostitution has marred the profession. Becoming a geisha was one of the few means a girl in the Edo period could gain an education and become independent. Let us take a brief look at the history of geisha.

Geisha are an icon of Japanese culture. Mystique and stigma surrounds the profession. Being a geisha is a profession, just as librarianship is a profession. Geisha are not prostitutes. Although, prostitution has marred the profession. Becoming a geisha was one of the few means a girl in the Edo period could gain an education and become independent. Let us take a brief look at the history of geisha.

Do you want sushi with that?

The ancestors of the fabled geisha were waitresses. Called saburuko, these people waited tables, made conversation, and sometimes sold nookie. These women were often daughters of once high-class families. Around 800 CE standards of beauty laid the foundations for both the future samurai and geisha classes. This continued up until a single man with a taste for business entered the scene.

Turning on the Red Light

In the Edo period of Japan (1600-1868), Hideyoshi Toyotomi had the idea to build a way for merchants to squander their wealth. The shogunate liked to take what the merchants earned. This practice kept the merchants from overtaking the samurai class. Samurai were often in debt to merchants. This wasn’t considered good for Japanese society. Japanese society at this time didn’t have taxes. The samurai would steal (legally, of course) from merchants to keep their debts under control. Because of this regular habit, there wasn’t much use in hording wealth. Wealthy merchants began spending their wealth on whatever wasn’t forbidden by the shogun. Silver, gold and silk were forbidden; they belonged solo to the samurai class. Toytomi decided there were better things to catch the wealth merchants either threw away or lost to the shogun: the Yanagimichi. The Yanagimichi was a pleasure district where sex, companionship, booze, music, gambling, and more were sold. These places literally had red lanterns to set them apart from the surrounding city. Red lights being associated with prostitution was not only a European idea.

Of course, the shogunate didn’t like the idea of red-light districts. The Yanagimichi was walled off in an effort to make it a headache for upstanding people to visit. All the walls did was make the district that much more enticing. Many districts focused on refining women to provide entertainment through dance, song, and conversation. Sex was icing or main course depending on the amount of coin in your pocket.

The pleasure districts grew popular enough that a constant influx of new girls was vital for keeping merchants interested. Zegen (what we would call pimps) started wandering the countryside and poor districts in search of…candidates. Zegen paid families that gave up their daughters. Surprisingly, this wasn’t considered bad. Many extremely poor families considered this practice beneficial. It gave their daughters a chance to have a steady source of food, fine clothes, and even education. These pleasure districts were sometimes preferable to a life a poor starving farmer’s daughter would experience.

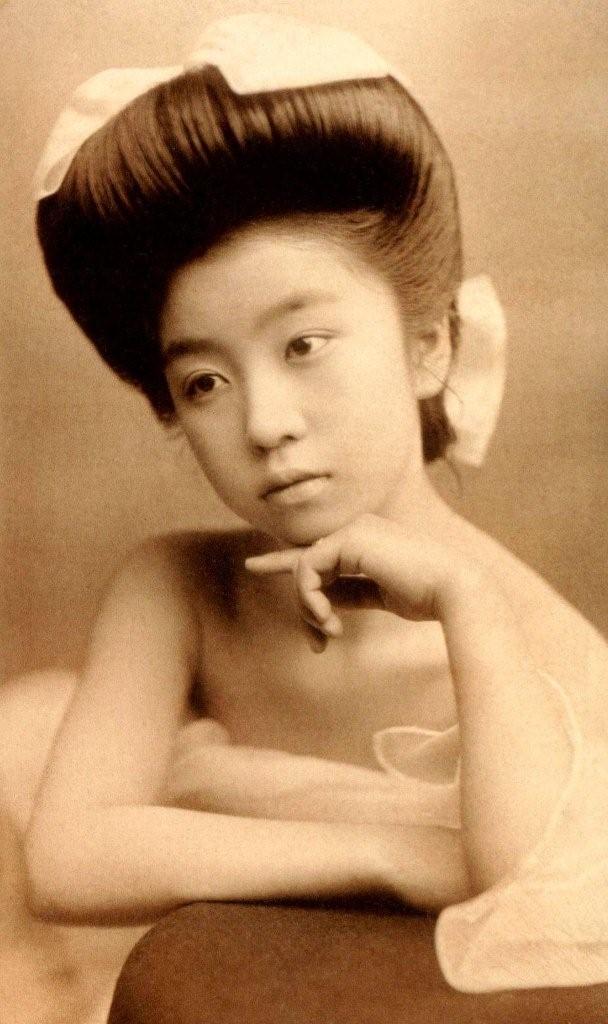

New girls would start as maids until they were old enough to become kamurof, what would become maiko in Kyoto. Maiko means “person of dance.” These are apprentice geisha. Kamurof would watch and learn from an older courtesan just like the future maiko would do. Gradually, the geisha developed from this tradition.

Selling Virginity

Girls were considered sexually mature at the age of 13. Most people in Japan around the 1700s tend to live between 38 and 45 years. What we consider the tender age of 13 was 1/3 of a person’s life span. So it made sense that boys and girls would be considered mature much earlier than what we would consider today. Courtesans underwent a rite of passage called mizuage around this age. This is where an apprentice’s virginity would be auctioned off to the highest bidder.

However, geisha did not practice this type of mizuage. This practice was limited to courtesans, or high class prostitutes.

However, geisha did not practice this type of mizuage. This practice was limited to courtesans, or high class prostitutes.

It was a habit of the Tokagawa Shogunate to classify prostitutes, artists, dancers, kabuki actors, and other professionals by beauty and accomplishments. The highest ranked people could choose the focus of their work and their patrons.Only the lowest ranged workers behaved as prostitutes. Even then, these women were expected to practice the arts.

As the visitors of the pleasure districts become more wealthy and powerful, what we would call geisha appeared. These women stopped selling their bodies and sold their skills in music, conversation, and culture. These women were not prostitutes nor were they wives. They were professionals who often had their own businesses. Called okiya, these businesses specialized in housing and training women to entertain at teahouses.

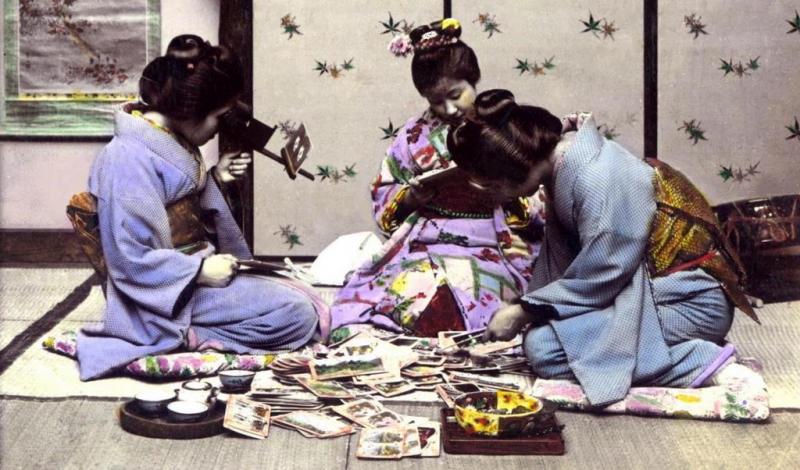

The Geisha of Tea, Dance, and Business

Teahouses played an important role in business ventures. Japan has long been a society focused on social norms and saving face. The role of teahouses and geisha was to provide a place where masks could be dropped. Men could relax and speak their minds. The job of the geisha was to keep conversation flowing (along with sake, alcohol) and create a relaxing atmosphere. Dance, song, drinking games, and conversations all served to help patrons relax. The white painted face that make geisha famous was the mask of civilization she wore for the men who hired her. This allows the men to get down to business while civilization in the form of a woman kept things from getting too out of hand. Teahouses were one of the few areas where men could drop the facades society expected. Politeness could turn to bluntness. A man could wear his own face for a change.

Stereoviews are images that create a 3D effect when looked at through a view finder like the one you see in the photo.

Geisha means “person of art.” Geisha are not prostitutes, especially modern geisha. While the profession has roots in both waitressing tables and selling sex, geisha draws first and foremost on the arts of poetry, dance, music, tea, and conversation. The profession lifted many women from poverty and allowed these women to become their own person. There are black marks on the profession: sexual abuse, slavery, debt, drunkenness. However, there were few opportunities for poor girls to gain an education and make her own way in pre-modern Japanese society.

Today, geisha is a profession girls may choose to enter. It is a profession that seeks to preserve traditional arts and culture against modernity. The apprenticeship follows the traditional ways with the exception of mizuage and a few other practices.

References

Bardsley, J. (2009). Liza Dalby’s Geisha: The View Twenty-five Years Later. Southeast Review of Asian Studies. Vol 31. 309-323.

Foreman, K. (2011). The Gei of Geisha: Music Identity and Meaning. Ethnomusicology. 55 [1]. Unversity of Illinois Press.

Hanley, S. (1974). Fertility, Mortality,and Life Expectancy in Pre-modern Japan. Population Studies. 28 [1]. 127-142.

Lockard, L. (2009). Geisha: Behind the Painted Smile.

McCormick J. (1956). The Mask and the Mask-like Face. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 15 [2]. 198-204.

Schultz, C. (2005). A Gentle Stroll Through Japanese Culture. History in the Movies. Retrieved from http://www.stfrancis.edu/content/historyinthemovies/memoirsofa%20geisha.htm.

Szczepanski, K. History of the Geisha: Japanese Female Artists and Entertainers. Retrieved from http://asianhistory.about.com/od/japan/a/History-of-the-Geisha.htm.

2 thoughts on “Geisha: Beginnings”