The Dark Presser. The Old Hag. The Ghost Presser. Alien Abduction. No matter what cultural form it takes, kanashibari excites and terrifies. Between 40-50% of people will have at least one experience of kanashibari in their lifetimes (Schegoleva, 2002). In the West, we know it as sleep paralysis.

Nightmares and sleep paralysis happen together during the second half of the night–REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. During this phase, the body disconnects from the brain so you don’t enact your dreams. Even automatic reflexes, such as kicking when the knee is tapped, are shut off. This isn’t a problem unless the brain wakes up before the body reconnects. This is what is called sleep paralysis or kanashibari (Schegoleva, 2002). When the brain wakes in this state, it is still dreaming, but your eyes are open and seeing the dreams. The brain struggles to understand what’s going on by substituting explanations from your culture–aliens, ghosts, demons, vampires, and other creatures. When the body and brain reconnect, the dreaming stops, but it can take seconds to 20 minutes for them to talk to each other again (Cox, 2015). Until then, you are at the mercy of the experience (Cox, 2015):

“I had one patient who was lying in bed and woke up to see a little vampire girl with blood coming out of her mouth,”says Brian Sharpless, a clinical psychologist at Washington State University and author of the book, Sleep Paralysis: Historical, Psychological, and Medical Perspectives. “This is an example of a really vivid, multi-sensory hallucination. She could feel this vampire figure grabbing onto her arms, pulling her, and saying she was going to drag her to hell and do all these terrible things to her.”

The first recorded experience appears in Al-Akhawayni’s 1st century Persian manuscript Hidayat. In 1664, the Dutch physician Isbrand van Diemerbroeck reported a case of sleep paralysis in a 50-year old woman. But it wasn’t until 1755 that nightmares and sleep paralysis became linked when Samuel Johnson defined the word nightmare. The earliest recording of sleep paralysis in Japan dates to the 12th century. The Japanese Emperor Konoe Tonno (1139-1155) experienced the sensation of chest compression sometimes associated with sleep paralysis. “Every night the emperor was oppressed by a mysterious agony which the holiest monks, working all their healing rites, seemed unable to relieve.” In 1153, Minamoto no Yorimasa (1104-1180) saved the emperor by killing a winged demon called Nue with an arrow (Orly & Haines, 2014).

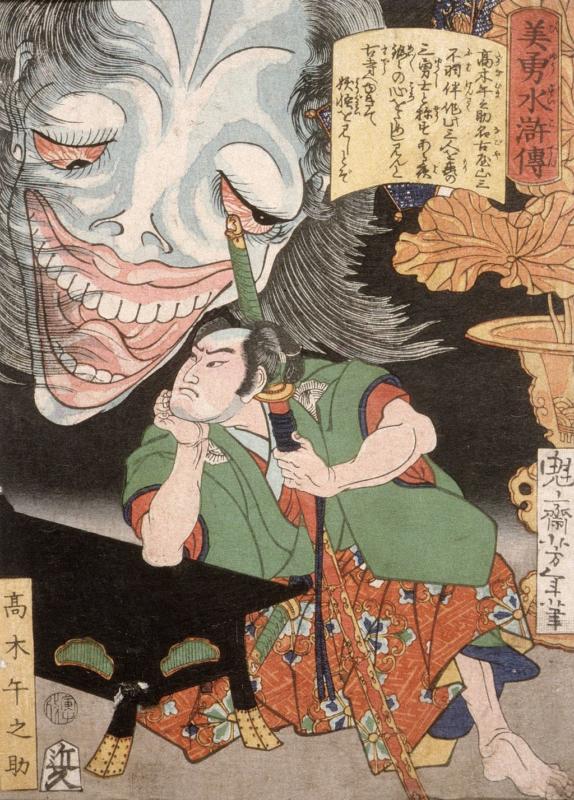

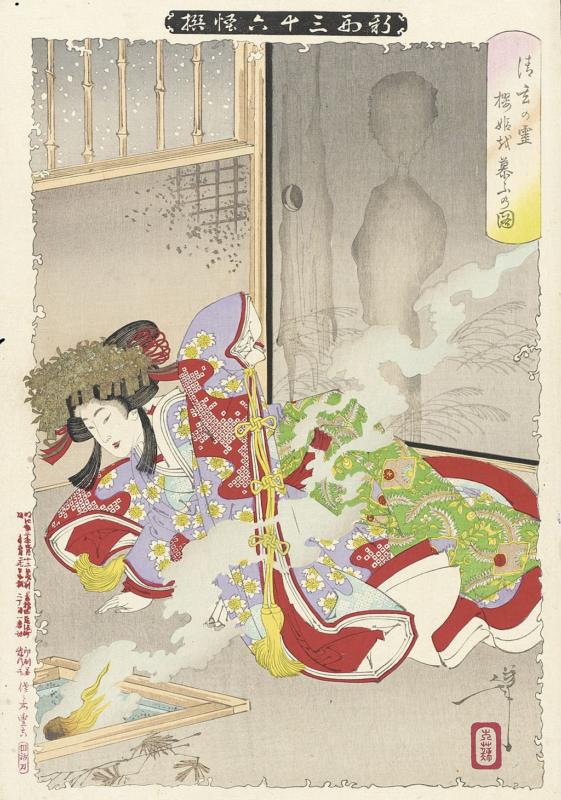

The association of sleep paralysis and spirits is found across cultures. The most common story is the Old Hag, which appears in Japan and in Europe. Typically, it involves an ugly woman, often dressed in white, sitting on the sleeper or making eerie sounds. The English word haggard comes from this experience. In some European stories, witches descend onto sleepers who are trapped in their beds. Haggard means “ridden by the hag” (Cox, 2015). However, other supernatural creatures are said to cause sleep paralysis. In Japanese folklore, kanashibari happens whenever a person is about to encounter a supernatural being. It’s something of a premonition (Yoshimura, 2015).

The word kanashibari comes from a medieval Japanese spell called kanashibari no ho, a paralysis magic practiced by priests of Onmyodo Shugendo of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. It’s thought the ability can be attained through intense ascetic training, and different groups developed different ways of casting the spell. In the book Shoku nihongi, the founder of Shugendo, En no Ozumu (634-701) used the spell to punish spirits who failed to collect water and firewood for him. Most often, the spell was used to subdue an opponent or expel an evil spirit by invoking Fudomyoo, the patron deity of Shugendo (Yoshimura, 2015). Kanashibari means “to immobilize as if bound with metal chains.” Kana means metal. Shibaru means to bind.

Who Experiences Kanashibari

While anyone can experience sleep paralysis, women and students are more prone to it (Arikawa & Templer, 1999). As many as 43% of Japanese students report at least one episode. It’s thought women and students are more prone to kanashibari because both have less control over their environment and because they have more disruption in their sleep cycles (Arikawa & Templer. 1999; Schegoleva, 2002).

Kanashibari’s nightmares focus on lack of control. After all, you can’t move during it. The frustration of not having control over your circumstances can come to the fore during your dreams. Despite this discomfort, students want to experience kanashibari. Some attempt to induce the experience by sleeping on their backs, which can help cause it. Others write “Get lost!” on a piece of paper, tear it up, and throw it away in an effort to anger spirits enough to visit that night. In fact, when researchers asked how to avoid kanashibari, students couldn’t offer solutions. They wanted to experience it rather than avoid it (Schegoleva, 2002). Here is an interview Schegoleva had with an 11-year old boy to give you an idea about kanashibari:

‘Yes, it happened when I was five. I remember lying in my bed, my body being pressed by someone in long white clothes. I could see my brother sleeping but could not move to free myself or scream for help.’

‘Was it a male or female figure?’

‘I immediately decided that it was a female. I don’t know why.’

‘You remember it quite well. How did it end?’

‘I felt that I could move my toes, and the same moment the ghost disappeared.’

‘Do you think it was a ghost?’

‘My brother told me next morning: so you had kanashibari and saw a ghost!’

‘Did you tell the other members of your family what had happened?’

‘No, but a few years later my mother asked if I had had kanashibari, and I said yes, and told her about it.’

‘Has it happened to you just once?’

‘In fact, the second time it happened soon after I spoke to my mother about kanashibari.’ [Laughs.]

‘How old were you?’

‘Well, it was about two years ago, so I was nine, I think. But I did not see anything, there was just this

strange annoying noise, like a glass breaking.’

‘Like glass breaking? Was there actually anything like glass around?’

‘No, and the noise was constant, not real, like glass broken into pieces – crrraasshhhh, as if something

big and fragile was being dropped on the floor.’

‘Were you frightened?’

‘No, the second time I knew what was happening and even found it funny, though the noise was …bothering me.’

‘And the first time, when you were five?’

‘I do not remember very well, but I think I should have been afraid.’

‘Do you know why people get kanashibari? Or how to get kanashibari?’

‘I am not sure, but some of my classmates should know, ask them.’

Media and Kanashibari

Kanashibari can be a terrifying experience if you don’t know what’s happening, or it can be a something a student seeks for a thrill similar to watching a horror movie. If you’d rather avoid the experience, sleep on your side and try not to stress. A regular sleep pattern helps too. About half of us will have at least one episode of kanashibari in our lifetimes. Kanashibari is one of the more mysterious parts of the human experience, one that links modern people with folklore that had long since understood what we are just coming to know.

References

Arikawa, Hiroko & Templer, Donald, et al. (1999). The Structure and Correlates of Kanashibari. The Journal of Psychology 133 (4) 369-375.

Cox, David (2015) Vampires, ghosts, and demons: the nightmare of sleep paralysis; tales of things that go bump in the night have existed for centuries, but they may in fact be a part of a surprisingly common neurological phenomenon. The Guardian. Nov. 2, 2015.

Orly, Regis & Haines, Duane (2014) NEUROwords Kanashibari: A Ghost’s Business. Journal of the History of Neuroscience 23 192-197.

Schegoleva, A. (2002). Sleepless in Japan: the kanashibari phenomenon. Electronic Journal Of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 2

Yoshimura, Ayako (2015) To Believe and Not to Believe: A Native Ethnography of Kanashibari in Japan. Journal of American Folklore 128 (508) 146-178.