At the end of January, I had the privilege to witness a benshi performance, which impressed me immensely. Finally, it led to me writing this blog post. So, what am I actually talking about?

In Japan, silent films were never truly silent

Western audiences may be faintly aware that in the first cinemas, at least a pianist used to accompany silent films, if there wasn’t an entire orchestra at hand. As we still experience today, music is very effective in conveying emotion, atmosphere, and a sense of urgency or suspense regarding the story unfolding on screen.

But in Japan, they went far beyond that. The story of cinema in Japan begins with imports of western movies, showing scenes that were strange and exotic to Japanese viewers. Thus, these scenes needed explaining, and this is where the origin of the benshi lies. Literally, the word means ‘orator’ or ‘speaker’, and benshi started out as ‘film explainers’. Soon, however, they also became commentators, narrators, entertainers and voice actors. Some may pinpoint the development to a single person – “Somei Saburo was the first of these narrators who could be called a benshi. Rejecting the oft-assumed role of playing outside observer, Saburo chose to imitate, voice, and personify the characters depicted on the screen.”[i] – but a parallel development seems more likely.

The artists…

Owing to their origin as explainers of western ‘exotic’ contexts, benshi tended to dress in western attire, commonly tuxedo and top hat.

This trend continues until present day, as the most famous of today’s benshi, Sawato Midori, performs in suit and bow tie – despite the fact that, unusual for a benshi then and now, she is a woman. The benshi I watched, Kataoka Ichirō, is one of her students. At the beginning of the performance, he remarked that at the height of benshi popularity, in the 1920s, there were over a thousand of them active in Japan. The most popular of them earned more than the Prime Minister! In fact, cinema goers didn’t go to see a specific movie for its director or its actors so much as for the benshi performing it.[ii] Now, however, there are only about 10 benshi left, and (as Kataoka assured us) he, at least, earns significantly less than the Prime Minister.

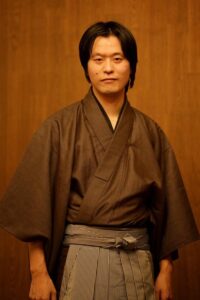

In contrast to the tradition, Kataoka dresses in traditional Japanese garb for his performances. About half of the short films he showed to us that night were period pieces, however, so it fit with the general theme.

…and the medium

In the old days, benshi manipulated the films they showed as they saw fit. To this day, they script their own texts for each movie, including the dialogue, even if the original script is available. Their performance unfolds in addition to, or sometimes at odds with, the intertitles. Often, though, Japanese silent films would not even have intertitles, since the directors knew the benshi would take care of narrative coherence and transition. Now, if the benshi’s dialogue took longer to perform than the scene allowed for, he would just instruct the man at the projector to lower the projection speed a little.[iii] This also led to a tendency in Japanese early film to use long, uninterrupted shots to allow the benshi time for his performance. Of cause, if he found a sequence boring, he might turn it into a comedic interlude and crank up the speed to get it over with.

In short, the main attraction was the vocal performance, and the film was only the raw material. Sometimes, the benshi would comment on the action, drawing attention to the fictitiousness of the story, in an almost Brechtian fashion.[iv] The relationship between film and ‘explanation’ was in fact reversed: “the images themselves being the illustration of an independently existing storyline.”[v]

Benshi might also use their position for political propaganda, as was the case with the war films during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904/5[vi]. Korean benshi likewise attempted to instigate rebellion against the Japanese colonial rule.[vii] The benshi‘s immense popularity was a major factor in the comparatively late start of sound film in Japan – but when progress finally took hold, the ‘talkies’ made the benshi obsolete.

Cultural contexts

Japan has a rich history of performance art, and the benshi can be linked to a number of them. The narrators of Kabuki theatre are prominent and visible.

So is the chanter of bunraku puppet plays, who also lends his voice to the silent puppet characters, much like the benshi voice the actors on screen.[viii] Furthermore, oral narrative performance art has a long tradition. In the Middle Ages, you could listen to biwa-hōshi, blind itinerant monks who recited war epics while accompanying themselves on a lute. To this day, there are performances of conversational comedy called rakugo.[ix] (Incidentally, the garments of rakugo performers may be another influence on Kataoka’s costume choice.) Even the master-student training system used by the benshi was adapted from other traditional Japanese arts.[x]

Because of these connections, benshi performing film were not a radically new thing, but rather a development based on older art forms. The links between theatre and film ran so deep that some theatres employed a number of benshi, some of them female, to feature in a single performance of “live dubbing”.[xi] For some time, there were also mixed shows, where part of the action was acted live on stage, part filmed beforehand and dubbed live.[xii]

Narrative: A performance of Kataoka Ichirō

It is at the end of January, 2017, in Trier, an ancient but small city in western Germany, close to the borders of Luxembourg and France. The Romans have left some impressive ruins, and Karl Marx was born in one of the strangely diagonal streets south of the market square. Today, the Broadway cinema, in cooperation with the department of Japanese studies of Trier university, presents a short film screening with benshi narration. At that time, I’m struggling to pinpoint the thesis of my Master’s dissertation. I have no clear idea what a benshi is, but it sounds interesting – especially since one of the films on the list is about Jiraiya, the toad mage, for whom I have a soft spot. Upon arriving at the cinema, I buy a bottle of German lemonade with real caffeine and sit down with a book. The performer is here already, and I shyly admire the traditional Japanese clothing he wears. Two other students of Japanese Studies join me at my table and update me on the goings-on in the student council. One of them is very excited because, he says, he is interested in everything about the Taishō period (1912-26). We sit down in the higher part of the screening room; it has a seating capacity of about a hundred and is 2/3 full at least. Someone from cinema management says a few words of greeting and presents Kataoka, not without mispronouncing his name, of course. Then Kataoka introduces himself. He has a pleasant, tough not very remarkable, speaking voice and is quite proficient in English, which is, sadly, quite unusual for a Japanese. At first, the audience is somewhat hesitant to respond to him (German stiffness, probably), but they mellow during the first film.

Lump Theft and Monkeys’ Masamune

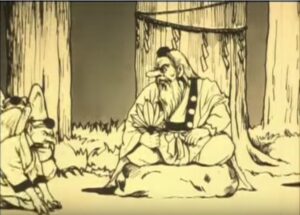

“I know this one”, I whisper to my neighbour, the Taishō enthusiast, as the screen flickers to grey and yellowish life. The first film is an animated short, about two old men with lumps and the karmic justice visited on them, quite by accident. “It’s on youtube.”[xiii]

How different it feels now, though! With the onset of the strange music – well, strange to modern Western ears at least, I cannot even discern the instruments – Kataoka’s performance beings. He does so in Japanese, of course, but someone has kindly provided subtitles, tailored to this specific event. As the introductory intertitle appears, the benshi’s voice turns into the solemn, melodious whine of a traditional Japanese narrator. He croaks like friendly raven once he voices the old man, produces the servile chatter of low-rank Tengu mountain goblins, as well as the rumbling laugh and growled anger of the goblin king. This feels just like anime now! If it weren’t for the moments when he, clearly on purpose, speaks even if characters are drawn with their mouths closed, or stays still when they seem to speak.

When that first movie is over, I am sitting on the edge of my seat for the next one, but that’s a fable with a somewhat dubious morale. A hunter trying to shoot an ape is wrong, but cutting a boar in half with a sword seems to be perfectly fine.[xiv] Between films, Kataoka gives us some facts in English about benshi practise and history.

Tarō’s Train

I am impressed by the third film because it mixes two styles we now mostly see as distinct. In a live-action sequence, a little boy receives a toy train from his father as a present. The dress and movement of the actors give me the feeling that historical knowledge only get you that far. This grainy movie has more life in it than any textbook on the Taishō era. Anyways, the boy finally goes to bed, enamoured with his new toy, and dreams of being a conductor. The dream sequence is animated; and full of anthropomorphic animals.[xv] It’s nice comedy and also instructive, explaining how to behave on a train. Seems to have been effective, since the Japanese are usually very pleasant, and quiet, train passengers. Kataoka takes the comedic tone of the piece to slip in a few jokes of his own, as one of ‘his’ characters metanarratively remarks on this being a black and white movie. In one instance, there was even a self-reflective joke in the subtitles!

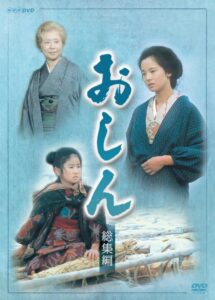

Tokyo March

The movie I like best, though, is Tokyo March.[xvi] It’s a complicated, kabuki-esque plot of love found and lost, mistaken identity, rivalry and family secrets, and Kataoka excels in portraying the characters- from young men to an old woman, from the sad heroine to the lecherous and finally gilt-ridden father.

Japanese speech patterns, of course, are highly codified by age, gender, class/profession and region. Which intonation, harshness or softness of voice, and what pitch one uses, how one refers to oneself, how questions, commands and states of emotional excitement are marked with specific particles, differs according to these criteria. I guess that makes the benshi’s voice-acting possible, if complicated. As an additional treat, the ending of the movie had some insensely, um, homosocial lines, which made my inner fangirl squee.

Contrasts

In fact, I keep forgetting the benshi’s presence because I get so absorbed in the characters and their story… I am only jolted out of it when Kataoka’s script diverges from the action. However, here he keeps a superb balance of immersion and alienation. By contrast, in his rendition of the Jiraiya movie, his narration seems to run off course a bit too much. He turns the confusing film into somewhat of a coherent story, but clearly this is only possible by intensively reinterpreting and repurposing the images. Perhaps I am getting tired, too. In any case, if you fancy a pretty young woman transforming into a slug, or warriors beaten back by lawn sprinklers, good entertainment, give it a try.[xvii] It’s the first special effects movie made in Japan, apparently.

The last film is a modern homage to silent film, and in direct contrast with the originals before, the difference is easy to spot. The pictures are too clear, the resolution too high, and the sudden tilts into yellow, blue or red seem exaggerated. There are scratch marks superimposed on the image, but it takes me only a few minutes to notice the repeating pattern. That being said, the story itself, about a jealous samurai and his bloody revenge, is interesting, and Kataoka once again amazes me with the variety of voices at his command.

Quite an experience, that was.

Afterthoughts

Benshi may have all but disappeared, but they sure have left a mark on the Japanese visual narrative. It’s not just Kataoka’s amazing versatility, which reminded me of some modern-day anime voice actors. Or that anime sometimes employ similar speaking styles in voice-over narration. In general, Japanese film features wide angles and long takes – perhaps in memory of the benshi who once needed the time to perform. And finally, voice-over and concluding narration is relatively common in Japanese live-action TV, which might be a legacy of the benshi.[xviii]

In addition, after the advent of sound film, some benshi who had lost their jobs became kamishibai artists. Kamishibai or paper theatre is a street art combining hand-drawn slides and vocal narration. It is seen a precursor of modern manga – the Manga Museum in Kyōto has a whole room dedicated to kamishibai, with an actor performing in period clothing. So, here we have another direct link with modern visual narrative.

Long story short, if you get the chance to see Kataoka or one of his colleagues perform, I strongly recommend going.

Notes and References

Website Sawato Midori: http://sawatomidori.com/eng/profile.html

An introduction of Kataoka Ichirō: http://hcl.harvard.edu/hfa/films/2012octdec/benshi.html

Video of a Kataoka Performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-SBXG4xY_M

[i] http://facets.org/blog/misc/the-tale-of-benshi-the-forgotten-heritage-of-japanese-silent-cinema

[ii] Yomota Inuhiko, transl. Uwe Hohmann: Im Reich der Sinne. 100 Jahre japanischer Film. Frankfurt am Main: Stroemfeld, 2007, p 26; see also J.L. Anderson: “Spoken Silents in the Japanese Cinema; or, Talking to Pictures: Essaying the Katsuben, Contextualizing the Texts”. In: Arthur Noletti Jr. & David Desser: Reframing Japanese Cinema. Authorship, Genre, History. Indiana UP, 1992, pp. 359-311, p. 261.

[iii] Yomota 2007: 44.

[iv] A slightly different take on the Brechtian comparision: http://www.altx.com/interzones/kino2/benshi.html

[v] Aaron Gerow: Visions of Japanese Modernity. Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: U of California P, 2010, p. 147.

[vi] http://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/content.cfm/a_brief_history_of_benshi. An extensive study of the open-endedness of the benshi performance, and the question if benshi closed or opened the interpretation of the filmic text, see Gerow 2010., chapter 4.

[vii] Yomota 2007: 44.

[viii] Anderson 1992: 265.

[ix] Yomota 2007: 45.

[x] Anderson 1992: 279.

[xi] Anderson 1992: 270. He uses the term katsuben, but I prefer beshi since that is the word Kataoka himself uses.

[xii] Anderson 1992: 271.

[xiii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShzmzcJM7QI

[xiv] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wY9fEdt9NRI

[xv] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYyeT9PMNXo

[xvi] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0eVO94JQ1Y Sadly, this version has no sound at all, whereas this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AC1pPawxWGY has music but only french intertitles.

[xvii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xt9GRKpeDtU with subtitles, but no music.

[xviii] Suggestions of this kind are made by Anderson 1992: 293 and Yomota 2007: 27, 45.

I no idea about benshi, this was fascinating to read. Thank you so much for such an insightful article into part of Japanese film history. It sounds like an amazing job, to be honest. I’m sad it’s kind of obsolete. I hope I get to see a performance one day. 🙂

Thanks for commenting!

I’m usually studying topics either about 80 to 100 years previous to, or about the same amount of time after, the era discussed here. In other words, late Edo or modern times 😉 So, writing this was a nice opportunity to dip into a different frame of mind, and I’m happy you liked it! The dwindling number of benshi is sad, that’s true. But on the other hand, the handful of benshi who ARE still around, do not seem to lack opportunities. I think Kataokas appearances in other countries are a very important way to keep benshi from being forgotten, and to keep researchers interested xD. To my knowledge, he has performed in continental Europe and the United States a couple of times in the last few years, so with a bit of luck (and travel expense) you might get your chance to see him :). I tried to find out where he’ll be appearing next, but there wasn’t much info online… He’ll be at Harvard Film Archive tomorrow, on the 10th of March (http://hcl.harvard.edu/hfa/films/2017marmay/benshi.html) and at the Film Forum New York on the 19th (http://www.hudsonsquarebid.org/neighborhood/event/the-art-of-the-benshi-a-live-performance-by-master-ichiro-kataoka). What I can gather from his twitter account, he’ll be back in Japan early April… It’s a shame hes doesn’t have a website with a calendar of upcoming performances!

Thank you very much for your blog post! I saw Kataoka-sensei’s performance in Trier too, and I was surprised by his use of metahumour and the “breaking the forth wall”-moments, especially in “Taro’s train”. I wanted to ask him, whether those puns were his idea and how much his script differs from the scripts of the Taisho period, but I missed the chance. Do you have any insights on that?

Thanks for commenting!

Surviving scripts or recordings of original Taishô- and early Shôwa-periodd benshi performances are rare, but what I could gather from secondary sources is that benshi did (sometimes at least) diverge from the filmic material or the original film script, if they had one, quite extensively. Metanarrativity is of course a postmodern concept, so I don’t think it’s appropriate to apply it to earlier works, but more than one source described benshi performances as ‘Brechtian’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epic_theatre) in their disruption of the theatric/filmic illusion through commentary. Therefore, I think we can assume Taishô period benshi did “break the fourth wall” in a somewhat similar fashion, and Kataoka-sensei followed that tradition, in a postmodern context 😉