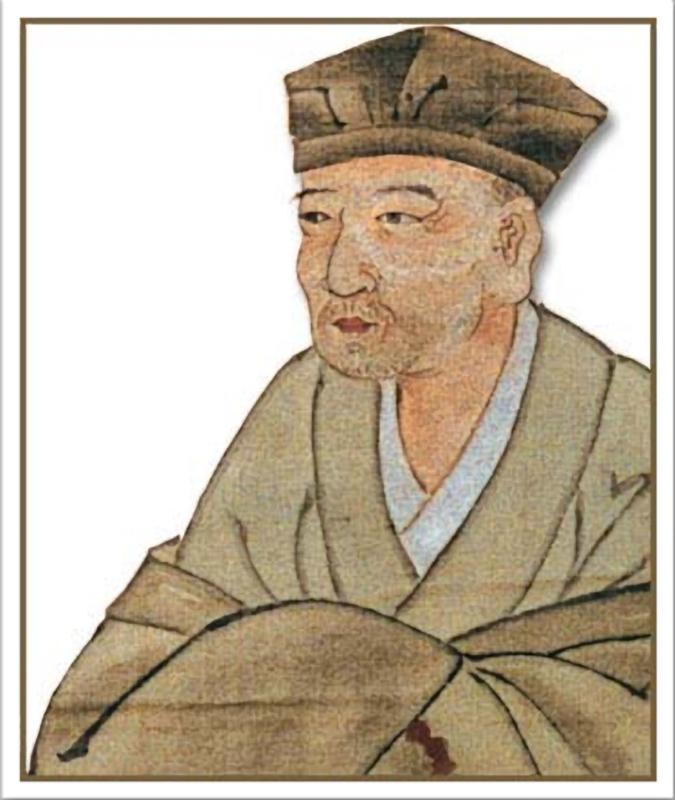

Matsuo Basho is known for his haiku, poetry consisting of 17 syllables divided into lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables. However, he is also famous for his travel memoirs, especially The Narrow Road of the Interior. Basho (1644-1694) was the son of a minor samurai and studied poetry, Zen Buddhism, Chinese learning, history, and Japanese literature. He often moved and traveled to teach poetry and to popularize haiku. He got his name from the cottage he lived in from 1680-1682 near the Sumida River in Edo. While he stayed there, one of his disciples presented him with a banana plant (basho in Japanese). Before long, people began to call his home the Banana-Plant Cottage, and Basho took the pen name we still know him by today. His given name was Munefusa.

Matsuo Basho is known for his haiku, poetry consisting of 17 syllables divided into lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables. However, he is also famous for his travel memoirs, especially The Narrow Road of the Interior. Basho (1644-1694) was the son of a minor samurai and studied poetry, Zen Buddhism, Chinese learning, history, and Japanese literature. He often moved and traveled to teach poetry and to popularize haiku. He got his name from the cottage he lived in from 1680-1682 near the Sumida River in Edo. While he stayed there, one of his disciples presented him with a banana plant (basho in Japanese). Before long, people began to call his home the Banana-Plant Cottage, and Basho took the pen name we still know him by today. His given name was Munefusa.

In 1684, he left Edo to visit his mother’s grave at Ueno. This journey appears to frame his work. We have to keep in mind that travel wasn’t easy. While Japan had a well-developed road system, travelers still had to endure weather, bandits, wild animals, dust, and the strain of long-distance walking. However, Basho seemed to relish the road-life. In 1687, he took a year-long journey that encompassed Ueno, Yoshino, Waka-no-ura and other areas. Much of his travels were practical. He would stay with students and patrons and compose poetry along the way. Basically, Basho took regular book tours. The Narrow Road of the Interior covers his travels of 1689. Here’s a list of his travel memoirs: The Journey of 1684, A Journey to Kashima Shrine, Backpack Notes, A Journey to Sarashina, and The Narrow Road of the Interior. Basho’s travel journals helped inspire ukiyo-e, such as Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido and various other travel series.

The Narrow Road of the Interior isn’t a journal as we think of it. While it teems with details and Basho’s experiences, it is partially fiction. The protagonist isn’t Basho, although the character channels Basho’s experience of failing health and travel hardships. The old man of Narrow Road wants to live like one of the wandering poets that fill Japanese literature. Basho, on the other hand, traveled to spread his brand of poetry, teach students, and secure patrons. He likely had an easier time traveling than he lets on since many of his associates were wealthy. We know this thanks to a diary kept by Basho’s traveling companion Sora.

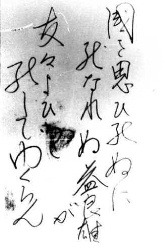

Narrow Road has a floating quality to it, much like other works of the Edo period. It taps into the long literary tradition of focusing on fleeting moments and chance encounters. Basho’s poetry often captures singular moments. Here is the beginning to give you a feel for how it reads:

The sun and the moon are eternal voyagers; the years that come and go are travelers too. For those whose lives float away on boats, for those who greet old age with hands clasping the lead ropes of horses, travel is life, travel is home. And many are the men of old who have perished as they journeyed.

I myself fell prey to wanderlust some years ago, desiring nothing better than to be a vagrant cloud scudding before the wind. Only last autumn, after having drifted along the seashore for a time, had I swept away the old cobwebs from my dilapidated riverside hermitage. But the year ended before I knew it, and I found myself looking at hazy spring skies and thinking of crossing Shirakawa Barrier. Bewitched by the god of restlessness, I lost my peace of mind; summoned by the spirits of the road, I felt unable to settle down to anything. By the time I mended my torn trousers, put on a new cord on my hat, and cauterized my legs with moxa, I was thinking only of the moon at Matsushima.

The introduction layers traditional Japanese literary symbols and philosophies. For example “my dilapidated riverside hermitage” references the ideas of wabi-sabi, of the beauty of aloneness and ruin. Likewise, Basho’s reference to the moon of Matsushima ties with all the other literary moon references. Japanese literature teems with what we would call hyperlinks. However, you don’t need any of these asides to understand Narrow Road. It offers an immediate, journal-feeling read. It is often hard to remember that the main character isn’t fully Basho but still has Basho’s observations and some of his sensibilities. This tension, and my desire to tease out what was Basho and what was not, made this read fun. Basho’s descriptions are also wonderful:

At one of the Three Barriers, Shirakawa has always attracted the notice of poets and other writers. An autumn wind seemed to sound in my ears, colored leaves seemed to appear before my eyes–but even the leafy summer branches were delightful in their own way. Wild roses bloomed alongside the whiteness of the deutzia, making us feel as though we were crossing snow. I believe one of Kiyosuke’s writings preserves a story about a man of the past who straightened his hat and adjusted his dress there. Sora composed this poem:

With deutzia flowers

we adorn our hats–formal garb

for the barrier.

All of the seasons play into this passage. Sora’s poetry appears throughout the Narrow Road as well. He and the old man Basho inhabits dash off a poem or two at each major location or landmark they reach. However, the work remains mostly prose. You will also read poems attributed to other people the travelers meet along the way, such as those one attributed to a Kyohaku:

Late cherry blossoms:

please show my friend the pine tree

at Takekuma

In many sections, Narrow Road reads almost like a travel brochure trying to entice people to visit a certain area. At times Basho speaks of ill health–he did suffer from poor health. Sometimes these episodes drive him to stay at an inn where he accounts of gossip he overhears. These scenes break up the pattern of traveling to a landmark and composing a poem. The effect makes the work read much like the travel journal it poses to be. It isn’t as personal or as warm as other journals like the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon. Instead, Narrow Road teems with imagery. It is also more accessible. You don’t need to be as versed in references to understand what Basho is saying. While Narrow Road of the Interior isn’t a diary, it has the feel of one. Basho’s travel journals aren’t as well-known outside of Japan as his poetry, and that is a shame. Give this a read if you are interested in Basho or traveling in Japan.

References

Craig McCullough, Helen (1990) Classical Japanese Prose. Stanford University Press.

I’m somewhat partial to Issa, though Bashō can be credited with much of what came to define the form… one with which there’s a certain contemplative loneliness implied. Early 5-7-5, 7-7 “tanka” started as the veiled back-and-forth messages of lovers, evolving into the “renga” of exchanged wit between temple monks (and sometimes nuns). But restricting an entire poem to the Zen of just the “hokku” (the first stanza) implied that the line had been written to no one.

The translations are tricky. Sometime, I think it’s best to dispatch the Japanese rhythm in order to preserve the meaning.

蝶と共に吾も七野を巡る哉

Chō to tomoni ware mo nana no o meguru Kana.

A butterfly my companion,

through seven fields

we wander!

— Kobayashi Issa, 1795

Rhythm and tone are lost on me anyway :D. I enjoy the poems of monks. They are often quite funny! Zen monks were surprisingly snarky.

Been meaning to read more of Basho, in particular his prose. Thanks for yet another well-written entry.

Basho remains surprisingly fresh. Of course, that is also thanks to good translators!